On Venice ’79

For Redux, Aperture magazine’s regular column on rediscovered books and writings on photography, we look at the catalogue that accompanied a one-time, photography-only biennial. This article appeared in Issue 17 of the Aperture Photograph App. It originally appeared in Aperture magazine #220, Fall 2015, “The Interview Issue.” By Lyle Rexer

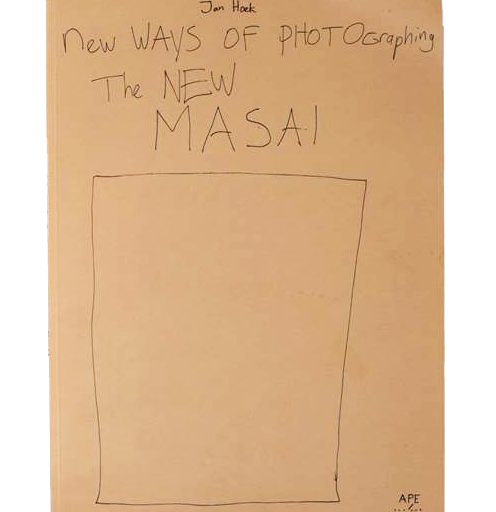

Cover of Photography: Venice ’79 (Rizzoli, 1979)

In 1979, Venice discovered photography—then turned its back on the medium. In a possible attempt to expand the Venice Biennale brand, the municipality, assisted financially by UNESCO and programmatically by the International Center of Photography, installed one of the largest photography exhibitions ever mounted in Europe. The catalogue, Photography: Venice ’79, expressed the tentative hope that this might be “the model for future such festivals.” Instead it was a one-off that, in retrospect, provides a revealing glimpse of where photography stood globally and the contradictions that would henceforth make any exhibition employing the generic term photography highly problematic.

Pages from Photography: Venice ’79 including photographs by Boris Kossoy and Carlo Bianco Fuentes

Like its off-year scheduling between two art biennials, photography’s position at the time might be described as “between”—between art and technology, between expression and documentation, between politics and personal vision. These familiar dichotomies in photographic discourse (the jacket copy called them a “quarrel”) played out in twenty-five separate exhibitions that made up Venice ’79. Looking over the table of contents, a contemporary reader recognizes the presentation not as a survey of photography in general but rather an argument for expressive art photography. In the words of Carlo Bertelli, one of the organizers, it was “an effective view of a continuity which has to be taken into account.” But what continuity? Exhibitions devoted to Alfred Stieglitz, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, and Diane Arbus emphasized their “mastery” and “consummate artistry,” but so did exhibitions devoted to work by Weegee, Lewis Hine, and Eugène Atget, none of whom thought of himself as an artist working in any sort of formal tradition or continuum. As critics of the time were beginning to point out, such an approach to the history of photography was selectively enfranchising to a high degree. The issue was not (and is not) that some photographers are chosen and some are banished from a pantheon, but that even in a sprawling exhibition like Venice ’79, the complex, polyglot character and usages of photography are sacrificed to ideas about what constitutes photographic art. After all, arty gestures and decisions are common in every area of photography, from fashion photography to snapshots. A more illuminating overview might have shown how photographers of many different kinds communicate with their audiences through choices that enable them to negotiate meaning. But such an approach would have opened the gates to a tide of pictures from vernacular and commercial sources.

Pages from Photography: Venice ’79 including photographs by Soichi Sunami, E.O. Hoppé, and Horst

Likewise, by 1979 there were many artists and photographers adopting critical and interrogative approaches to photography. Few of them were included in Venice ’79. Lucas Samaras, Ugo Mulas, Robert Heinecken, and Joan Fontcuberta were the most prominent conceptualists. Perusing the catalogue, my favorite is Marialba Russo, a photographer previously unknown to me. Her sequence, in both black and white and color, shows a fake childbirth on a southern Italian street. The baby is a doll and the mother a swarthy, bearded man in a dress. Shot in a frenzied style, it comments not only on the documentary mode (exemplified in Venice by exhibitions of work by W. Eugene Smith and Robert Capa) but also on the political issues of class and regional division. Politics always complicates discussions of what is and is not art, especially in photography, where pictures are so often used for propaganda. One of the most important of Venice ’79’s exhibitions, Hecho en Latinoamérica (Made in Latin America), demonstrated the force of photography as political witness but also the confusions of a theory and an exhibition that sought to define photography in expressive and formal terms. On the one hand, this collection of three hundred works by photographers from across the region, originally assembled for an exhibition by the Consejo Mexicano de Fotografía, constituted a bid for artistic recognition by marginalized countries.

It was the largest selection of such photographs to appear in Europe, and it contained the work of many great artists, including Graciela Iturbide from Mexico, Fernell Franco and Carlos Caicedo from Colombia, and Geraldo de Barros from Brazil. On the other hand, the introduction by Raquel Tibol dismisses art photography in favor of documentary work—but then turns contemptuously on mere “mimetism.” She demands that the work be anchored in social realities but also in the imagination. She extols mechanical modernity but decries technical perfection. Above all, she sets a wholly political agenda for photography, arguing that it should be aligned against imperialism and “oligarchic exploitation.” This edict sanctioned works displaying both kitsch symbolism and harrowing realism. It underscored dramatically that photography serves many ends, often at the same time, and thus can’t be contained (or understood) by the boxes curators put it in. The increasing incorporation of photography into art biennials partly explains why there would be no Venice ’81. (The Venetian organizers started an architecture biennial the next year, which has continued.) More important, however, the very amplitude of Venice ’79 showed the futility of trying to say something definitive about a medium that is as fluid and ubiquitous as the water surrounding Venice.

Pages from Photography: Venice ’79

Click here to find Aperture magazine on the Aperture Foundation website.