Vision & Justice: Guest Editor’s Note

In 1926, my grandfather was expelled in the eleventh grade in New York City for asking where African Americans were in the history books. He refused to accept what the teacher told him, that African Americans had done nothing to merit inclusion. He was expelled for his so-called impertinence. His pride was so wounded that he never went back to high school. Instead, he went on to become a jazz musician and a painter, inserting images of African Americans in scenes where he thought they should—and knew they did—exist. The endeavor to affirm the dignity of human life cannot be waged without pictures, without representational justice. This, he knew.

American citizenship has long been a project of vision and justice.

When I was asked to guest edit this special issue devoted to photography of the black experience—the first of its kind for Aperture—I could think of no other theme. No matter the topic—beauty, family, politics, power—the quest for a legacy of photographic representation of African Americans has been about these two things. The centuries-long effort to craft an image to pay honor to the full humanity of black life is a corrective task for which photography and cinema have been central, even indispensable.

Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil. Today, we’ve been able to witness injustices in a firsthand way on a massive scale that would have been unimaginable decades ago. We have had to ask ourselves questions that call upon powers of visual analysis to read, for example, the image of Eric Garner’s killing, virally disseminated through social media, or to understand the symbolism in Dylann Roof’s self-styled portraiture before his killing of the Emanuel 9 in Charleston. Being an engaged citizen requires grappling with pictures, and knowing their historical context with, at times, near art-historical precision. Yet it is the artist who knows what images need to be seen to affect change and alter history, to shine a spotlight in ways that will result in sustained attention. The enduring focus that comes from the power of the images presented in these pages—from artists such as Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young, Deborah Willis and Jamel Shabazz, to Lorna Simpson and LaToya Ruby Frazier—move us from merely seeing to holding a penetrating gaze long enough that we consider what is before us anew.

Courtesy the National Park Service, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Washington, D.C.

This issue takes its conceptual inspiration from the abolitionist and great nineteenth-century thinker Frederick Douglass, who understood this long ago. In a Civil War speech, “Pictures and Progress,” Douglass spoke about the transformative power of pictures to affect a new vision for the nation. This issue opens with that historic framework—Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s writing on Douglass’s prophetic, probing ideas and theories about the medium of photography at the dawn of the photographic age. Douglass, the most photographed American man in the nineteenth-century, argued that combat might end complete sectional disunion, but America’s progress would require pictures because of the images they conjure in one’s imagination.

We come closer to understanding Douglass’s vision of justice with the generation of imaginative photographers and artists represented by projects in this issue, from Leslie Hewitt’s and Lorna Simpson’s assemblages of archival pictures that speak to the complex legacies of the civil rights movement to Awol Erizku’s stylish studio portraits, in which he appropriates iconic poses of Old Master paintings. We see it in the photographs of Roy DeCarava, Carrie Mae Weems, Frank Stewart, and Jamel Shabazz, who never let us forget the dignity of black life, and in those of Deborah Willis, who has also long chronicled the history of the field. We are fortunate to have essays in this issue by a wide range of scholars, artists, and writers—including Teju Cole, Margo Jefferson, Claudia Rankine, Robin Kelsey, Cheryl Finley, and Leigh Raiford, alongside historians Nell Painter and Khalil Gibran Muhammad and musicians Wynton Marsalis and Jason Moran—who offer invaluable insights about the significance of this relationship between art and citizenship exemplified by the works selected for these pages.

Courtesy Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum

Published in the last year of the Obama presidency, this issue marks a time of unparalleled visibility for an African American family on the world stage. Yet this era must also be defined by the emergence of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, the stagnated wages of working-class citizens, and growing impatience with mass incarceration. Devin Allen, a young photographer who came to national attention through his prolific Instagram feed, chronicled the unrest in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Gray in police custody. Suddenly the streets of 2015 looked like memories of 1968 though the circumstances are dramatically different. Radcliffe “Ruddy” Roye, who has propelled the classic genre of street photography into the age of social media, asks, in his continuous stream of images, how we should imagine dignity in the face of oppression. Catalyzed by events just over fifty years apart, Dawoud Bey’s powerful meditation on the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Alabama and Deana Lawson’s portrait series on the families of victims killed in 2015 at Mother Emanuel in Charleston, South Carolina, speak to the legacy of the African American church as a target for terrorism and a refuge of grace.

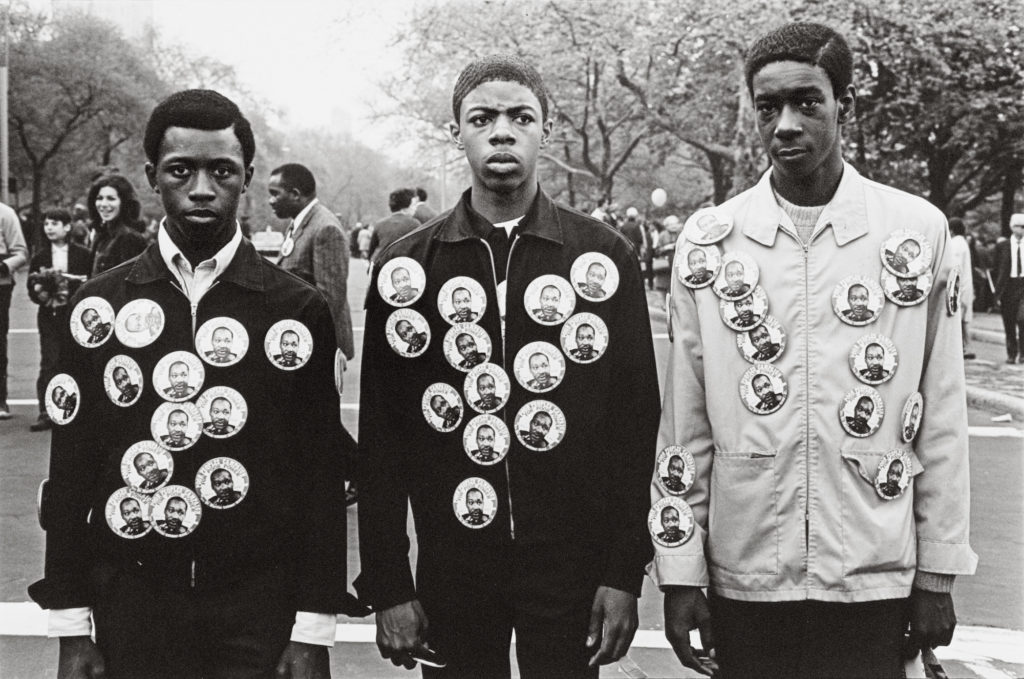

We often see the nexus of vision and justice as a retrospective exercise, chronicling the recent past. We saw this most notably with what I would call Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “aesthetic funerals”: the urge after his death to visually unfurl images, ideas, epic visions of African American culture as if to secure the horizon line that felt suddenly in doubt. We saw it in Benedict Fernandez’s photograph taken on April 5, 1968, of three young boys with their torsos covered in buttons of King’s Poor People’s Campaign, as if they were laying out the body of King across their own. At the time of year when Fernandez took this photograph, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was planning an exhibition called Harlem on My Mind to open in 1969, which used the visual poetics of an unfurling, a spreading out of an archive, to show the development of Harlem. As Bridget R. Cooks describes in this issue, Harlem on My Mind was designed as a tour of Harlem, a processional through thirteen chronologically ordered gallery displays of photographs, dominated by James VanDerZee. It also had a most unusual feature: a closed-circuit television showing exhibition visitors at the Metropolitan real-time footage of pedestrians passing on 125th Street and Seventh Avenue. The now nearly unimaginable feature of a camera displaying Harlem as a distant culture from that of the Upper East Side still offers a vivid reminder—art is often the way to cross the gulf that separates us.

What does it take to work toward representational justice? In this issue, we are fortunate to have answers through a frank discussion between the trailblazing filmmaker Ava DuVernay and cinematographer Bradford Young and an interview with a pioneer of film, Haile Gerima, followed by Carla Williams’s reflections on the role of the groundbreaking, 1970s-era Black Photographers Annual for the development of this photographic field. What did it mean for African American photographers to create this journal dedicated to fine-art photography, given that more visible magazines, including this one, rarely included work by African American photographers? That short-lived publication would pave the way for historians such as Deborah Willis, among others, who have devoted their careers to elevating the life stories and images of African American photographers, whose immeasurable contributions to the medium are only just becoming widely recognized.

Saturated with images, we now live in a world where the power of an image is so self-evident, so common, that it is easily dismissed. Douglass was writing at a time when it could not be forgotten. As I wrote in The Rise, it was a modernist vision at the dawn of the age of photography that might take decades, if not a century or more, to be made clear.

How many movements began when an aesthetic encounter indelibly changed our past perceptions of the world? It was an abolitionist print, not a logical argument, which dealt the final blow to the legalization of the slave trade—the broadside Description of a Slave Ship (1789). The London print of the British slave ship Brookes showed the dehumanizing statistical visualization with graphic precision—how the legally permitted 454 men, women, and children might be accommodated by treating humans as more base than commodities (though the ship Brookes carried many more, up to 740). The image it conjured in the mind was intolerable enough to help abolish the institution; the broadside served in parliamentary hearings as the evidentiary proof of slavery’s inhumanity.

© the artist and courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

How many went to Selma because they were moved by images of injustice on their television? How many, like Brown v. Board of Education constitutional lawyer Charles L. Black, Jr., saw that segregation was wrong after being moved by the power of an artist, in this case the “genius” of the trumpet playing of Louis Armstrong? Armstrong’s genius, Black would state, “opened my eyes wide, and put to me a choice”: to keep to a small view of humanity or to embrace a more expanded vision. Once Black made the choice, he never turned back. This is what aesthetic force can do—create a clear line forward, and an alternate route to choose. Later Black would say that, in many ways, this was the day he began “walking toward the Brown case, where I belonged.” Black never forgot it. He held an annual Armstrong listening night at Columbia and Yale, where he would go on to teach constitutional law, to honor the power of art in the field of justice and the man who caused him to have an inner, life-changing shift.

The gravity of this connection between vision and justice is crucial to understand, as we live in a polarized climate in the United States; sociologists tell us that people now congregate, live, worship, play, and learn with those like themselves more than ever before. Save for constructed societies, we come into close contact with those who do not share our political and religious views less and less. How we remain connected depends on the function of pictures—increasingly the way that we process worlds unlike our own. The tool we marshal to cross our gulf is irrevocably altered vision. The imagination inspired by aesthetic encounters can get us to the point of benevolent surrender, making way for a new version of our collective selves.

Shortly after my grandfather died, I went back to the house where he lived in Virginia, the white clapboard structure nearly ready to sink back into the earth. I stood in that pass-through chamber off of the dining room where he painted. The dining room looked empty, absent the paintings and drawings we’d often splay out on the table as if nourishment of an essential kind. Guest editing this issue of Aperture has brought me to that moment again, mindful of my very personal commitment to the artists, writers, playwrights, and filmmakers who, like my grandfather, see this inextricable nexus between race, art, and citizenship. I dedicate this issue to my grandfather’s memory and to all those who are working tirelessly to honor the full spectrum of human life.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.