5 Photography Exhibitions to See This Fall

From modern dance to postwar portraits, here are this fall’s must-see exhibitions in New York.

Alex Prager, Orchestra East, Section B, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

Lehmann Maupin, 201 Chrystie Street, New York

Through October 23, 2016

Through a synthesis of photography, film, and performance, Alex Prager’s third major solo show at Lehmann Maupin considers the fraught relationship between artist and audience. At the center is Prager’s eponymous film La Grande Sortie (2015), commissioned by the Paris Opera Ballet, which dramatizes the famed prima ballerina Émilie Cozette’s anxious return to the stage after an “unexplained hiatus.” The audience—populated by veteran performers of the company—is the subject of multiple still images reproduced as archival pigment prints. Like much of the Los Angeles–based artist and filmmaker’s most recognizable work, this exhibition reflects on aspects of staging, crowd dynamics, and the assumption of roles. Focusing on sections of the audience who are indicated by their location, the film portrays what appears to be a cross-section of “types” in the crowd: the young, the elderly, the single, the enthralled, the bored. The cinematic artifice in Prager’s photographs borrows heavily from Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills but is equally informed by William Eggleston’s striking use of color and sense of portent in the ordinary. Known for her lush, almost cartoonish images of Hollywood screen types and richly stylized mise-en-scènes, here Prager casts her subjects in a more tenebrous light, and inhabits a kind of twilight zone between life and affect.

Marco Breuer, Untitled (C-1807), 2016

© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Yossi Milo Gallery, 245 Tenth Avenue, New York

Through October 29, 2016

In this striking body of new work, Breuer presents a series of chromogenic paper prints marked by semi-organic shapes—paroxysms of searing color and tense edges. Pursuing stark articulations of form, the German photographer rips into the surface of light-sensitive paper. Through this process and other abrasive, incisive techniques that have become the hallmark of his practice, areas of highly saturated color emerge. Studies for these works and various pieces of ephemera, many in woodblock ink on black card stock paper, illuminate the highly methodical work process underlying the seemingly spontaneous violence of production. (Breuer’s previous drawing implements have included twelve-gauge shotguns, the guts of electric frying pans, modified turntables, razor blades, and power sanders.) The raw binary structures exposed—between negative and positive space, color and monochrome, field and line—are concerns that painters and sculptors have extensively explored, but rarely modulated so lucidly by artists utilizing photographic techniques. By taking up these formal interests, Breuer strides into a realm dominated by abstract painting but with a photographer’s studio and a sculptor’s sense for subtraction. In a separate but closely related series, Breuer photographed his body mimicking the abstract shapes produced in his cameraless images. These whimsical yet elegant distillations are reproduced in a sixteen-page black-and-white newsprint tabloid accompanying the exhibition.

Sergei Tcherepnin, Games, 2016. 10 double-sided hanging color photographs mounted on sintra, copper, brass, arduino, touch sensor, sound

Courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

Murray Guy, 453 West 17th Street, New York

Through October 15, 2016

Vaslav Nijinsky’s Jeux stands as one of the most veiled, prophetic works in the modern canon of ballet. Composed by Claude Debussy and performed only a few times after it was completed in 1913, Jeux (Games) was a high-concept dance of flirtation instigated by a man and two women when a tennis ball is lost during a match. The piece, which drew upon classical reference by replicating poses from antique frescoes and sculptures, connected sports and sexuality, and predicted the link between the clubby, insular language of athletic teams and queer culture. In a new series of ten double-sided color photographs floating down from the ceiling, the performance and installation artist Sergei Tcherepnin substitutes tennis for basketball, and replaces the cast with three male athletes, a return to Nijinsky’s homoerotic intentions. (Jeux was originally meant for three male dancers.) His brightly colored prints are hooked up to sensors that, when touched, trigger a sound component. In an adjoining gallery, several sculptures set up a domestic tableau, which Tcherepnin characterizes as a “private locker room,” but more closely resembles a bedroom. Photographs taken in a gay cruising area on Fire Island known as the Meat Rack hang on the wall. Chairs, a lamp, and a side table all produce recorded sounds when touched. Despite the almost comical, animating effects of these audio-extensions, the images and objects remain resolutely static. As visitors create their own soundscape and impose effects on non-responsive objects, they reenact Najinsky’s probing scenario. There is a lightness, however, in Tcherepnin’s reinterpretation of the art of the chase. The exposed wiring systems, the fumbling ballplayers—all allude to an honest, if accidental, unbuttoning of the rules of attraction.

Zoe Leonard, DP Camp, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Hauser & Wirth, 32 East 69th Street, New York

Through October 22, 2016

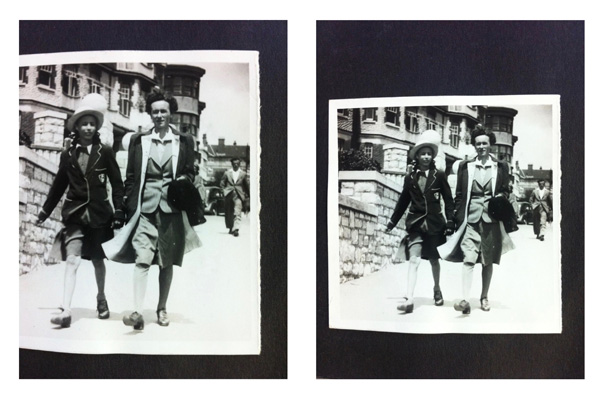

This spare but extensive exhibition sprawls across three floors of Hauser & Wirth’s Upper East Side townhouse gallery and seamlessly knits together a personal history of war and displacement with the rise of popular photography in the twentieth century. Taking a conceptual approach to reproduction, Zoe Leonard displays re-photographed snapshots of her mother’s family, who fled Poland and were stateless for more than a decade after World War II. Though Europe was in disarray in the immediate postwar years, the ever-growing industry of amateur photography nonetheless emerged as a cultural force. The reach of this mass phenomenon is represented by volumes of 1950s-era instructive manuals with titles such as How to Make Good Pictures and Photography Is …, collected in piles throughout the gallery. Together, the personal snapshots and generic books contrast society’s insatiable desire for artistic and technological advancement with the unpredictable realities of lived experience: while thousands of books were published on how to improve one’s photography technique, millions of people were struggling with the conditions of displacement. With her deliberate obfuscation of some reproductions, Leonard appears to question the nature of historical truth as it is represented by photographic documentation; in some of her images we see only the glare or torn edge of an original photograph’s surface. Illustrated history, Leonard implies, whether personal or global, is fragmented, partial, and opaque.

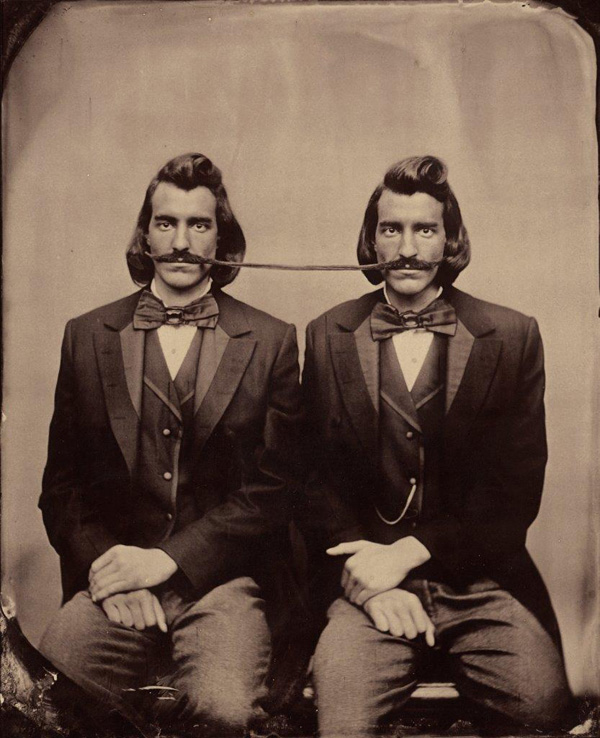

Stephen Berkman, Conjoined Twins, undated. Albumen print from wet plate collodion negative

Courtesy the artist and Howard Greenberg Gallery

A New and Mysterious Art: Ancient Photographic Methods in Contemporary Art

Howard Greenberg Gallery, 41 East 57th Street, New York

Through October 29, 2016

“It is now more than fifteen years ago that specimens of a new and mysterious art were first exhibited to our wondering gaze,” the British art critic and historian Lady Elizabeth Eastlake wrote in 1857. Fifteen decades later, the “ancient” photographic methods of the nineteenth century, and the vaporous, alchemical images they render, once again appear “new and mysterious.” Curated by Jerry Spagnoli, a leading practitioner of the daguerreotype, this beguiling exhibition presents works by contemporary artists mining photography’s rich technological and material history. The most notable are those in which artists use heritage techniques to amplify contemporary visions. At just over seven feet long, Vera Lutter’s gelatin silver print of the Venetian skyline, Campo San Moise, Venice, VIII: March 4 (2006), produced using a camera obscura, dominates the room. In an age of endless mutability and reproducibility, her unique negative print suspends the image of a sinking city in a single, eternal moment. The acclaimed Japanese photographer Takashi Arai has been making daguerreotypes since 2010 to create individual records, or “micro-monuments,” of subject matter relating to nuclear history. His piece A Maquette for a Multiple Monument for B29: Backscar (2014), from the series Exposed in a Hundred Suns, shows how an historic practice becomes, by virtue of size, instantly contemporary.