8 Photobooks by Contemporary Women Photographers

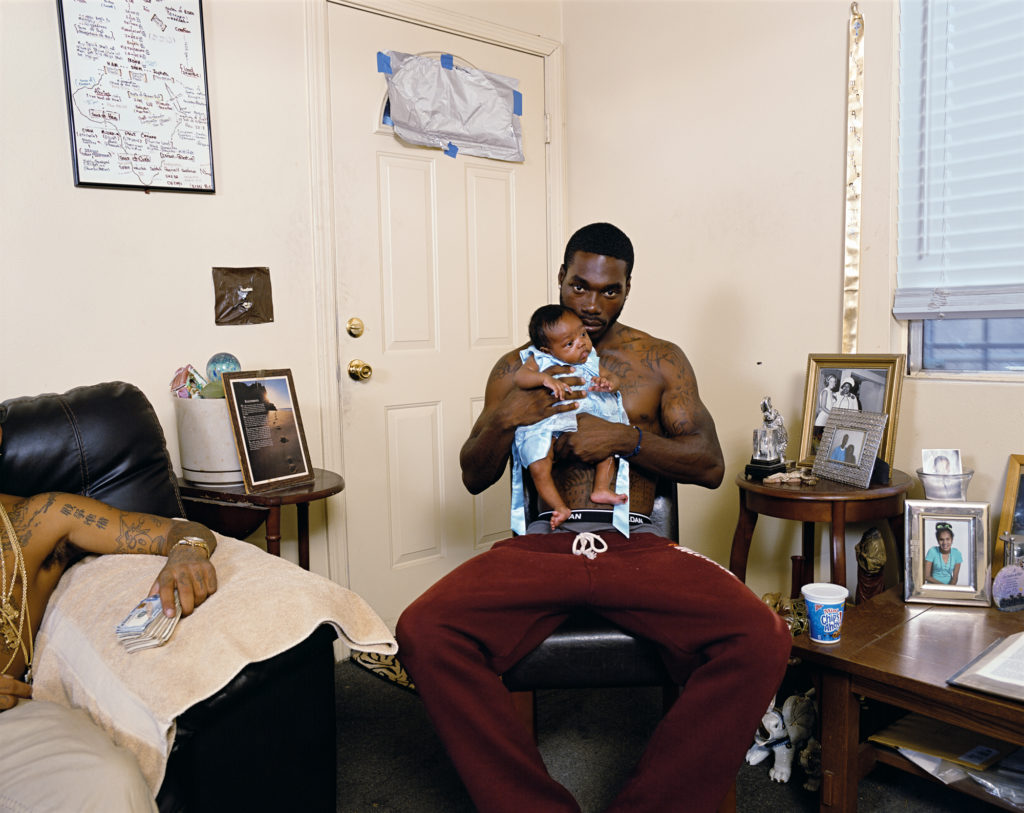

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013

Courtesy the artist, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Since its founding in 1952, Aperture has elevated the voices of women artists and published important works by female photographers, including inspiring volumes by Nan Goldin, Deana Lawson, Sally Mann, and more. Now, in celebration of Women’s History Month, we’ve gathered eight essential titles by today’s leading contemporary women artists.

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

Caspian: The Elements by Chloe Dewe Mathews

Between 2010 and 2015, Chloe Dewe Mathews traveled through the beguiling region surrounding the Caspian Sea, photographing throughout Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Russia, and Iran. Documenting the vastly diverse peoples, politics, and geographies of Central Asia, centering always on the great inland sea, Dewe Mathews found that elemental materials like oil, rock, and uranium have become integral to daily life. In photographs that range from stark and primordial to lush and mysterious, Dewe Mathews records the rituals and components of this resource-rich area—such as immersive acts of healing in water and oil, the almost mythological presence of flames, and drastic changes in landscapes and cities due to sudden economic shifts.

Brought together in the 2018 volume Caspian: The Elements, Dewe Mathews’s investigation is a powerful document of the ways humans are inextricably linked to this enigmatic and much-coveted land. As Sean O’Hagan writes, “Sooner than we think, these images will become historical, a record of a place that no longer exists in quite the same way, but that nevertheless thrives against all the odds in a time when, in much of the world, the age of miracles has passed into myth.”

Courtesy the artist

The Notion of Family by LaToya Ruby Frazier

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s award-winning first photobook, The Notion of Family, offers an incisive exploration of the legacies of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Examining this impact throughout the community and her own family, Frazier intervenes in the histories and narratives of the region. Setting the story across three generations—her grandma Ruby, her mother, and herself—Frazier’s statement becomes both personal and political. Documenting the struggles and interactions with family and the expectations of community against the demise of Braddock’s only hospital, Frazier reinforces the idea that the history of a place is frequently written on the body as well as on the landscape.

In The Notion of Family, Frazier knowingly acknowledges and expands on the traditions of classic black-and-white documentary photography, enlisting the participation of her family, her mother in particular. In the creation of these collaborative works, Frazier reinforces the idea of art- and image-making as transformative acts, means of resetting traditional power dynamics and narratives—both those of her family and of the community at large.

Courtesy the artist

In recent years, Rinko Kawauchi’s photographs of the tender cadences of everyday living have begun to swing further afield from her earlier work. Contemporary Japanese photography has not often been concerned with the natural landscape; the seemingly ever-expanding cityscape of Tokyo was more of a preoccupation up until 2011, a moment when the presumed order of things—natural, civic, and otherwise—was upended by the combined disasters of tsunami, earthquake, and human miscalculation. Kawauchi’s most recent work is not a commentary on natural disaster and unnatural aftermath. It is, however, an acknowledgment of larger forces at play.

This shift was first marked in the 2013 publication Ametsuchi, in which Kawauchi concentrated on the volcanic landscape of Japan’s Mount Aso and the historic Shinto ritual sites as a larger reflection of spirituality. Kawauchi has gone on to expand her inquiry even further in Halo. Throughout the volume, Kawauchi photographs three main themes: Lunar New Year celebrations in China (where a five-hundred-year-old tradition calls for molten iron hurled in lieu of fireworks), the southern coastal region of Izumo, and her ongoing fascination with the murmuration of birds along the coast of Brighton, England. The resulting images knit together a mesmerizing exploration of the spirituality of the natural world, contemplating cycles of time, implicit and subliminal patterns of nature and human ritual, and the larger spiritual forces at play.

Courtesy the artist

Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures

The North American landscape is an enduring symbol of romance, rebellion, escape, and freedom. At the same time, it’s a profoundly masculine myth: cowboys, outlaws, Beat poets. Photographer Justine Kurland, known for her utopian images of American landscapes and their fringe communities, sought to reclaim this space with her now-iconic series Girl Pictures. Taken between 1997 and 2002, Kurland photographs staged scenes of teenage girls as imagined runaways, offering a radical vision of community and feminism.

Kurland portrays these girls as fearless and free, tender yet fierce. They hunt and explore, braid each other’s hair, swim in sun-dappled watering holes. Yet throughout all of Kurland’s photographs, her subjects pay no mind to the camera, or to the viewer, existing outside of patriarchal expectations and ideals. Kurland imagines a world at once lawless and utopian, an Eden in the wild. “I wanted to make the communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experiences as primary and irrefutable. I imagined a world in which acts of solidarity between girls would engender even more girls,” writes Kurland. “Behind the camera, I was also somehow in front of it—one of them, a girl made strong by other girls.”

Courtesy the artist, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph

Over the last ten years, Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors, to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s landmark first publication, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. Last year, Lawson went on to become the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson’s images portray the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Deana Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain

Throughout her thirty-year career, An-My Lê has photographed sites of former battlefields—spaces reserved for training for or reenacting war—and the noncombatant roles of active service members. Lê is part of a lineage of photographers who have adapted the conventions of landscape photography to explore the structures of conflict that have long informed American history and identity. Yet she is one of the few who have experienced the sights and sounds associated with growing up in a war zone, having evacuated her home country of Vietnam as a teenager in 1975.

In 2020, Aperture and Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art copublished the first comprehensive survey of Lê’s work, On Contested Terrain, featuring formative early works, as well as her well-known series Small Wars, 29 Palms, and Events Ashore, and Lê’s most recent photographs from the US-Mexico border. “Lê’s photographs are balanced, quiet, and nuanced works of art that offer the viewer an opportunity for contemplation,” Dan Leers writes. “She invites us to examine our own perception of, and involvement in, war as something that is not straightforward or clear-cut.”

Courtesy the artist

Diana Markosian: Santa Barbara

In Santa Barbara, Diana Markosian recreates the story of her family’s journey from post-Soviet Russia to the US in the 1990s. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Markosian’s mother, Svetlana, placed an ad through a Russian agency that read: “I want to see America, and meet a kind man who can show me the country.” After corresponding with a man who responded named Eli, Svetlana moved to America with her two young children. Markosian’s family settled with Eli in Santa Barbara, California, a city made famous in Russia when the 1980s soap opera of that name became the first American television show broadcast there.

Weaving together reenactments by actors, archival images, and stills from the original Santa Barbara TV show, Markosian reconsiders her family’s story from her mother’s perspective, relating to her mother for the first time as a woman, and coming to terms with the profound sacrifices Svetlana made to become an American. Brought together in Markosian’s debut monograph, Santa Barbara, the series offers an innovative and compelling hybrid of personal and documentary storytelling.

Courtesy the artist

Perfect Strangers: New York City Street Photographs by Melissa O’Shaughnessy

For the last seven years, Melissa O’Shaughnessy has photographed daily on the streets of New York. In her photographs, fleeting moments of light, people, and the chaos of the city collide in surprising, poignant, and humorous ways—from the intersection of businessmen and tourists, shoppers and grand dames, to families frozen in confusion, wonder, pain, frustration, sometimes even joy. “Woven into her cast of characters are the lonely, the lost, the soulful, the broken, and the proud,” Joel Meyerowitz writes. “O’Shaughnessy has fallen for them all—perfect strangers.”

O’Shaughnessy’s first monograph, Perfect Strangers, presents a refreshing addition to the tradition of street photography. As one of a growing number of women street photographers contributing to this dynamic genre, O’Shaughnessy enters the territory with clarity and a distinctly humanist eye. Yet, looking at it today offers an unintended, yet powerful, impact: a hopeful and joyous reminder of New York’s pre-COVID parade of life.