Jo Spence: Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella, 1982

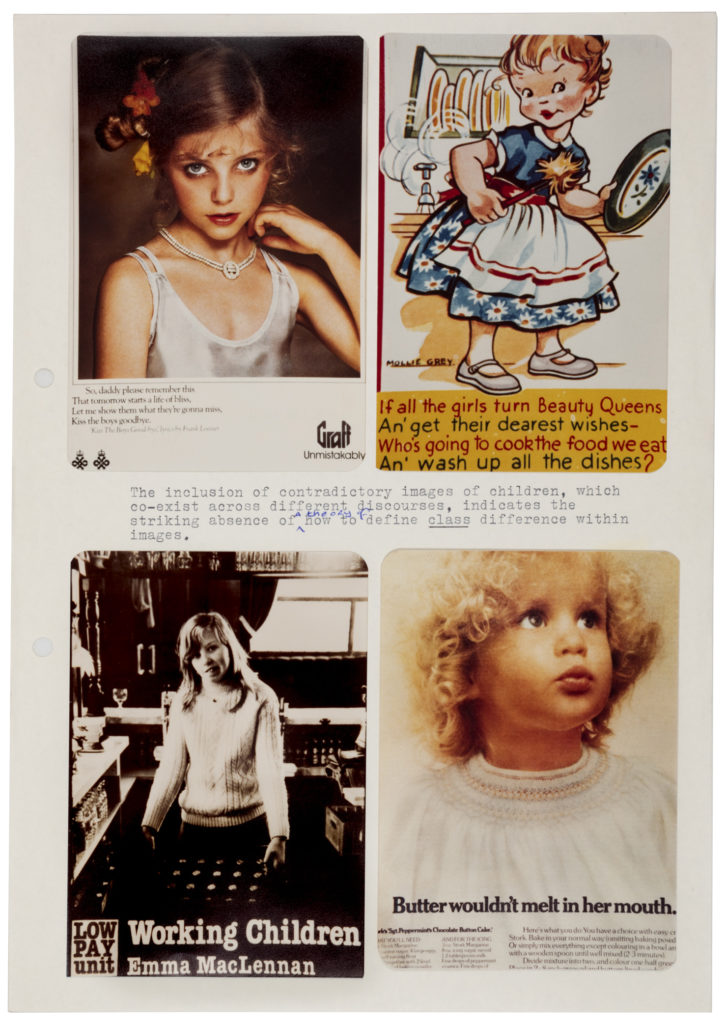

“How do we take a story like Cinderella out of the archives, off the bookshelves, out of the retail stores and attempt to prise out its latent class content? Its political and social uses?” So wrote the late British artist Jo Spence at the beginning of her 1982 university dissertation, “Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella.” In this formative illustrated text—republished last year by RRB Photobooks for the first time in its entirety—Spence traces the roots of the age-old tale across time and media, and she finds the shadow of Cinderella everywhere. By deconstructing the evolution of the story through pantomime and folklore, picture books and literature, children’s toys, Disney, and even in the latent messaging of hundreds of advertising images and newspaper headlines, she maps the endless ways the story has been mobilized throughout the decades.

It becomes clear early on in Fairy Tales and Photography that the context from which it emerged is crucial to its reading. When Spence was completing her thesis, she was living in London, and Margaret Thatcher was prime minister. In circumstances echoing the messages at the heart of “Cinderella,” class warfare was particularly intense, and Thatcherism was rigorously rooted in the idea of aspirational politics. The iconic royal wedding of Prince Charles and Diana had taken place in July 1981, attracting an estimated 750 million viewers in 74 countries, and the public and media reaction was nothing short of overwhelming. Spence was vocally anti-royal; a left-leaning activist in a conservative country, but nevertheless, she found inspiration through fairytales. For her, “Cinderella”—in its historical treatment of gendered labor, family politics, beauty, and love—was the perfect socialist subject. Slowly, she realized she could use it to interrogate the power structures that shape our lives.

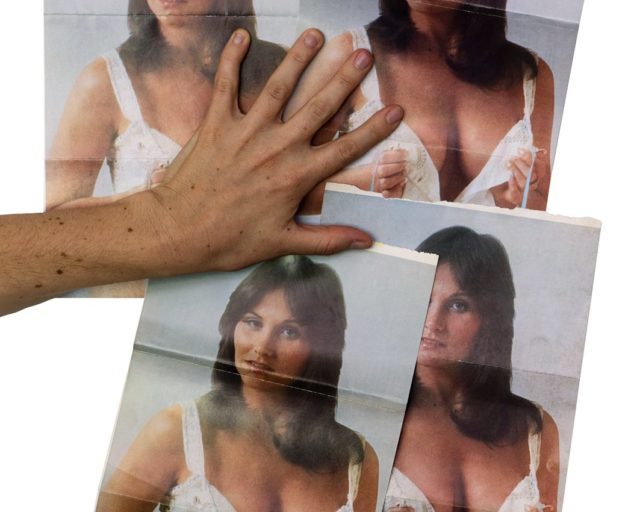

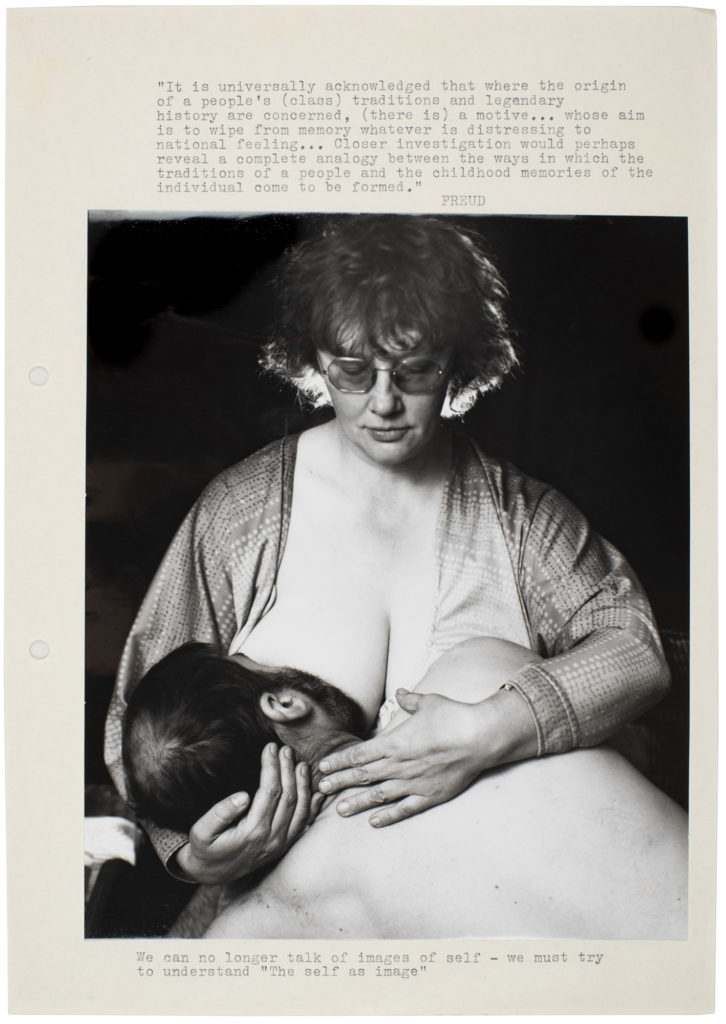

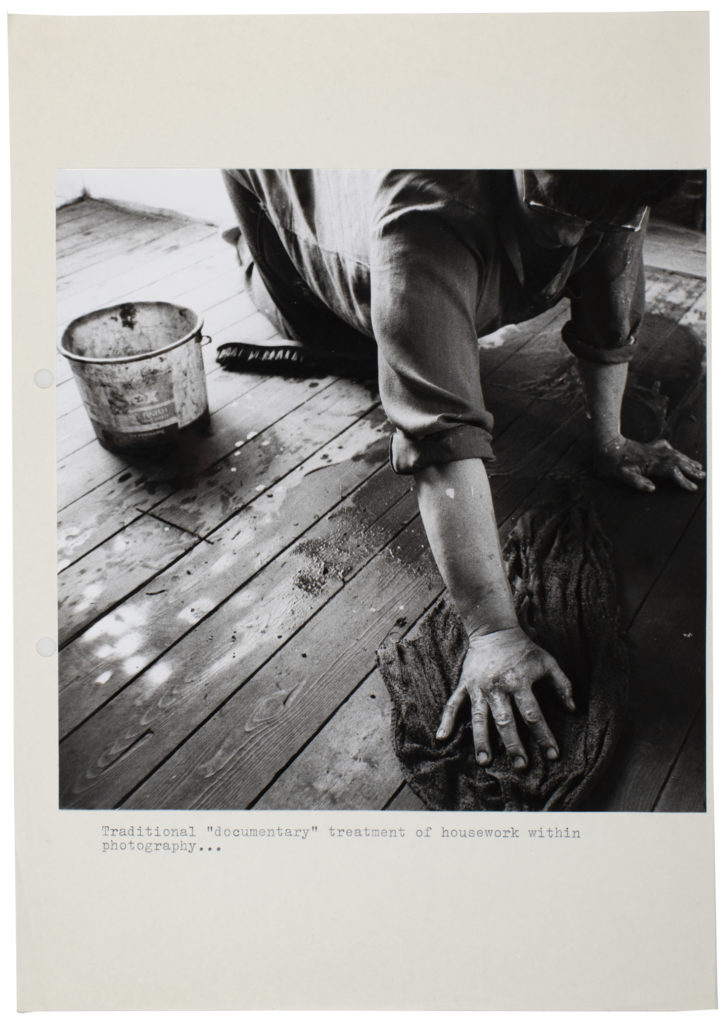

In painfully vivid detail, Spence shows how stories like “Cinderella” condition us from childhood to assume our places in society, teaching readers how to behave appropriately and what to expect from one’s station in life. As her own form of visual resistance, she conjures herself into various roles, refusing to be boxed in, and masquerades at turns as the protagonist, the fairy godmother, and the ugly sisters too. It’s hard not to look upon these acts of self-representation in Fairy Tales and Photography with a strange mix of sadness and bemusement. Her work was comedic, but it was also tragic and hauntingly prescient. “I want to be happy. I can transform myself,” she scrawled in red ink around a self-portrait of herself dressed as a fairy, reminding us of the work she made, years later, on female autonomy and mental health. And in another image from 1982, she assembles a still life of household items and a plastic bust, the price tag “65p” written across one breast. This one in particular feels like a pre-echo of her diagnosis with breast cancer later that year and of her final work attacking the monetization of public health-care systems—made before she lost her battle with the illness in 1992.

Princess Diana’s name has reentered the British news cycle recently, when the BBC finally apologized for its manipulative treatment of her in a controversial and infamous 1995 TV interview. I thought of Spence when this happened and about how the scholar Marina Warner—who knew the artist personally and writes an accompanying text for the publication—said Spence was always “acerbic” about the national love of Diana and the media construction of her as “the people’s princess.” Spence died five years before Diana did, and so she never got to see how that fairy tale went awry. There was more than a little of “Cinderella” in Diana’s story, which became one shaped increasingly by the politics of representation and the power of the camera. “How trenchant [Spence’s] response would have been to the paparazzi’s pursuit of Diana,” Warner notes.

“I am not sure what sort of a ‘future’ photographic theory is offering me at the moment,” Spence wrote in the final pages of her chapter on photography. “I am no longer sure who I am talking to; my photography and writing are fragmented, differing from day to day.” As it turns out, and though it was unknown to her at that time, Spence would spend the next two decades grappling with the medium, its social power, and its limitations, while adding a great deal to the canon of photographic thinking by probing its potential as both educational and therapeutic tool.

Courtesy RRB Photobooks/The Hyman Collection

Later, in her musings on photography, she riffs on the language of fairy tales to reflect on her work so far. “It is impossible ever after . . . to round off arguments neatly,” she said. When she wrote this text, she was a radical emerging artist, outspoken but unsure, and her metamorphosis was just beginning. Spence’s approach to art making was always one of obsession and excess, and she gathered and gathered research, never truly willing to streamline or minimize what she wanted to say. We can see the seedlings of this clearly in Fairy Tales and Photography, and that’s really the beauty of it. It was, in the end, a way of working she carried with her for the rest of her life.

Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella was published by RRB Photobooks in 2020.