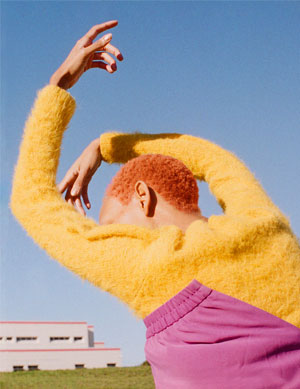

Bruce Conner, Bombhead, 2002

© Conner Family Trust, San Francisco/ADAGP, Paris

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, the threat of nuclear war seemed abstract—even anachronistic. Recent geopolitical tensions, however, have reminded us that its reality remains contemporary. The Atomic Age, an exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris, feels timed to explore the recrudescence of those anxieties. It shows how artists have responded to modern physics as well as the possibilities of extinction-level destruction. It also makes a compelling case for how advances in nuclear science led to major innovations in art. Throughout, artworks across a variety of media—from some of the first artistic representations of atoms (Hilma af Klint), through painting responding to fears of nuclear annihilation (Yves Klein) and audio recordings exploring post-Hiroshima trauma (Yoko Ono), to more formal experiments using radioactivity (Sigmar Polke)—appear alongside documentary material. At its best, this creates a compelling dialogue between primary sources and interpretations through art.

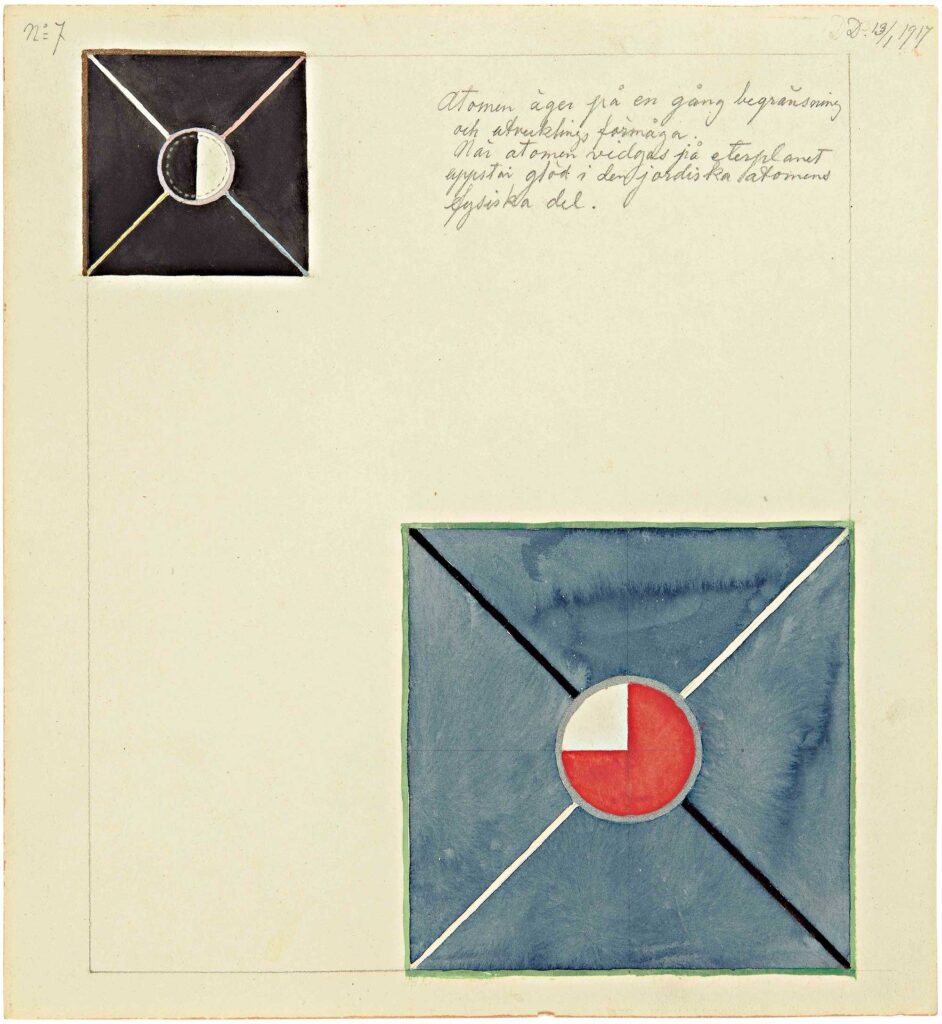

Courtesy the Hilma af Klint Foundation

© Musée Curie

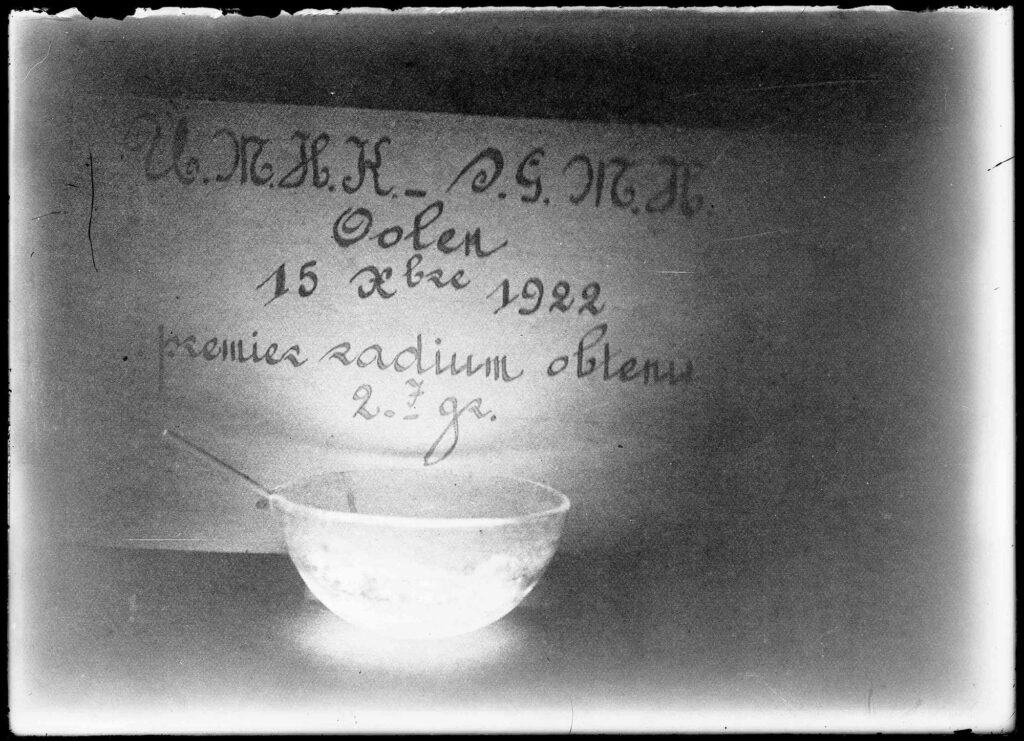

The exhibition starts out strong. After a large Barnett Newman abstraction, the first room presents a mix of artworks and historical records related to radioactivity and the scientific discovery of the atom. An edition of Marcel Duchamp’s La boîte verte (1934) appears next to the work of Niels Bohr, who made the first successful model for the atom, suggesting that Duchamp’s theory of the “infrathin” was possible because of atomic physics. Early notes and photographs by Henri Becquerel, the man who discovered radioactivity in 1896, are installed in poetic juxtaposition to Pierre Huyghe’s Dance for Radium (2004), a series of prints of the curator Jenny Jaskey dancing in a phosphorescent dress. Huyghe’s work references the modernist dancer Loie Fuller’s Radium Dance (1911), which she performed to a private audience, in a costume laced with radioactive salts provided by Marie Curie, who was in attendance.

© Estate of Sigmar Polke, Cologne/ADAGP, Paris

© the artist

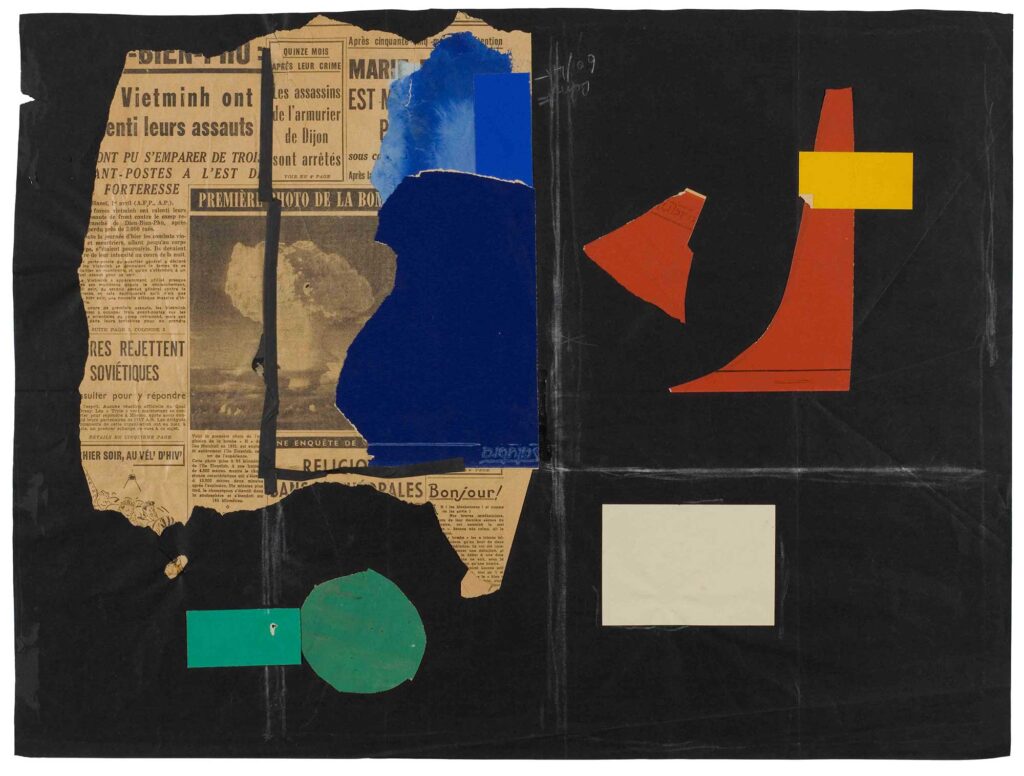

The Atomic Age follows chronologically from early atomic innovations to the invention of the bomb, from Hiroshima to the postwar period, though it doesn’t quite reach the present. While the first room sets the stage for meaningful interplay between archives and art, the documents at times feel supplementary. A wall of pictures of the Manhattan Project, for instance, displays prints of the Trinity Valley test explosions of 1945, with a timeline. Across from it is a screening of Dominque Gonzalez-Foerster’s Atomic Park (2004), an experimental film shot in White Sands Park, near Trinity Valley. The film’s footage echoes the ominousness captured in the snapshots, yet placing them next to each other reduces photography to an instrumental role, instead of creating a conversation between the various media.

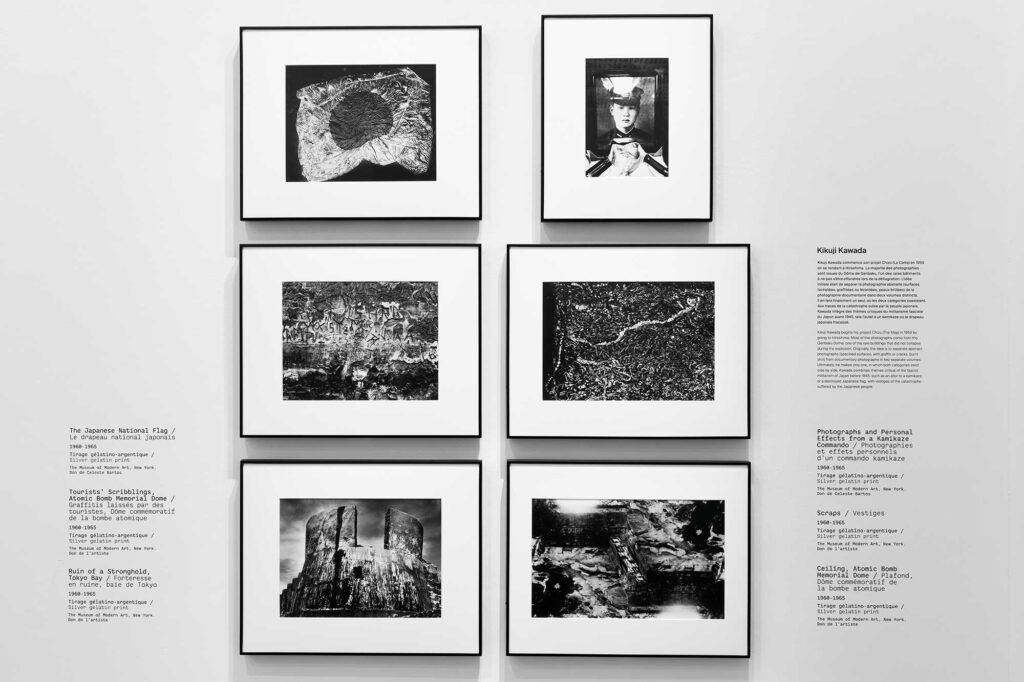

The contradictory nature of documentary images—to provide information about the world and produce a depiction of it—holds an unsettling power when considering something as unthinkable as nuclear destruction. When successfully placed next to art that interprets the facts, the effect can be chilling. A wall of photographs of the bombing of Hiroshima, for example, taken by both American occupying forces and Japanese photographers, is exhibited near the work of photo-conceptualist Hiromi Tsuchida. Tsuchida’s haunting conceptual triptychs (1979–97) show trees—pine, camphor, cherry—close to the epicenter of the bomb. He photographed them twice: once in 1979 and again in 1993. A map of Hiroshima locates the proximity of the trees to ground zero. The triptychs are shown next to the artist’s portraits and testimonies of survivors (1945–79). Their simple descriptions of telephone poles burning, followed by phrases of unease—“Am I alive or in a different world?”—renders the event in haunting detail. Nearby, Isamu Noguchi’s Atomic Head (1957), a sculpture that looks halfway melted, further blurs notions of documentation and representation. Photographs from Kikuji Kawada’s series Chizu (The Map; 1960–65) include pictures of Genbaku Dome, the structure that survived the explosion, and of graffiti, words scrawled by tourists, perhaps as commemoration, perhaps as witness. These seemingly abstract images contain within them much more than what is depicted.

Courtesy Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

Certain artworks, however, such as Bruce Conner’s Bombhead (1989), risk being reduced to spectacle. In the context of Conner’s output, this collage fits into a larger critique of postwar American society, but here, it feels too illustrative of the show—even appearing on the poster. The same happens, though to a lesser degree, with room after room of modernist paintings: Surrealism (including pieces by Wols and Wolfgang Paalen), Abstract Expressionism, the Milanese anti-nuclear art movement Mostra, and Arte Povera. Outside of the documentation of Mostra, these rooms almost constitute a different exhibition entirely, tracking a particular postwar response to nuclear anxiety in painting. Some of their titles include the words atomic or nuclear, which alone feels tendentious.

© Fondation Le Corbusier/ADAGP, Paris

Courtesy Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

All the while, archival material threads its way through Atomic Age—from architectural renderings of bomb shelters to pictures of protests, from files to rare books. At one point, there’s a small selection of documentation from an anti–nuclear war exhibition in 1963, staged by Situationist International in Odense, Denmark, where gallery-goers were encouraged to fire BB guns at heads of state of nuclear powers. A defaced target of Charles de Gaulle attests. Near that, a subtly disquieting series presents a timeline of nuclear tests throughout the colonized world, which includes photographs of France’s first test, in 1960, conducted in the Algerian desert during the war for independence, one of the more horrifying flexes post-Hiroshima by a nuclear power during a military conflict. Documentary images like these—which picture the effects of an explosion on the local population and landscape—reflect the sober state of the world far more powerfully than a Jackson Pollock painting. In the end, Atomic Age spurs us to consider something difficult to confront—but which, for our own survival, we must.

The Atomic Age: Artists put to the test of history is on view at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris through February 9, 2025.