Anna Ostoya, Politics & Passions (MACK, 2021)

“Our book was supposed to be published in the summer of 2020. Then the virus came. What’s your take on the last year?”

So begins one of the several conversations in Politics & Passions (MACK, 2021), a stunningly multifaceted collaborative book in which the artist Anna Ostoya revisits a 2002 essay of the same name by the political theorist Chantal Mouffe, and repurposes her own artistic archive to create a dialogue in images and words. It’s a complex revisiting—and a manifest reminder that all art and theory is inherently collaborative. It’s also an exchange of image and text, as Ostoya finds in Mouffe’s work the “inspiration to make things differently.” The “experience of looking,” Ostoya notes, “has been always connected with a political, historical, and personal reflection. It immediately raises the questions ‘what was?’ and ‘what is?’.”

In her 2002 essay “Politics and Passions: The Stakes of Democracy,” Mouffe offers a bold critique of the abiding politics of neoliberalism and a warning about what it enables: the upsurge of right-wing populism. She attributes the effectiveness of the right to the appeal of the stories it tells about itself. Worrying and wondering about how the left might radicalize democracy, about how to resist the status quo and prevent violence, Mouffe asserts the need for equally passionate counternarratives that move beyond moral condemnation of the “other” side. She convincingly argues for the futility of such condemnation, however emotionally satisfying it might feel; historically, shouting “capitalism is bad” has proved a losing strategy.

In 2009, Ostoya made of Mouffe’s essay a booklet of textual collages. Compelled and convinced by Mouffe’s ideas—and struck by Mouffe’s uncanny prescience—Ostoya revisits the original essay, her 2009 booklet adaptation of it, and a decade’s worth of her own artwork to create a new Politics & Passions (or, to render “Politics and Passions” anew). In this 2021 version, Ostoya reproduces her 2009 textual intervention and composes for it a series of twenty-five composite portraits.

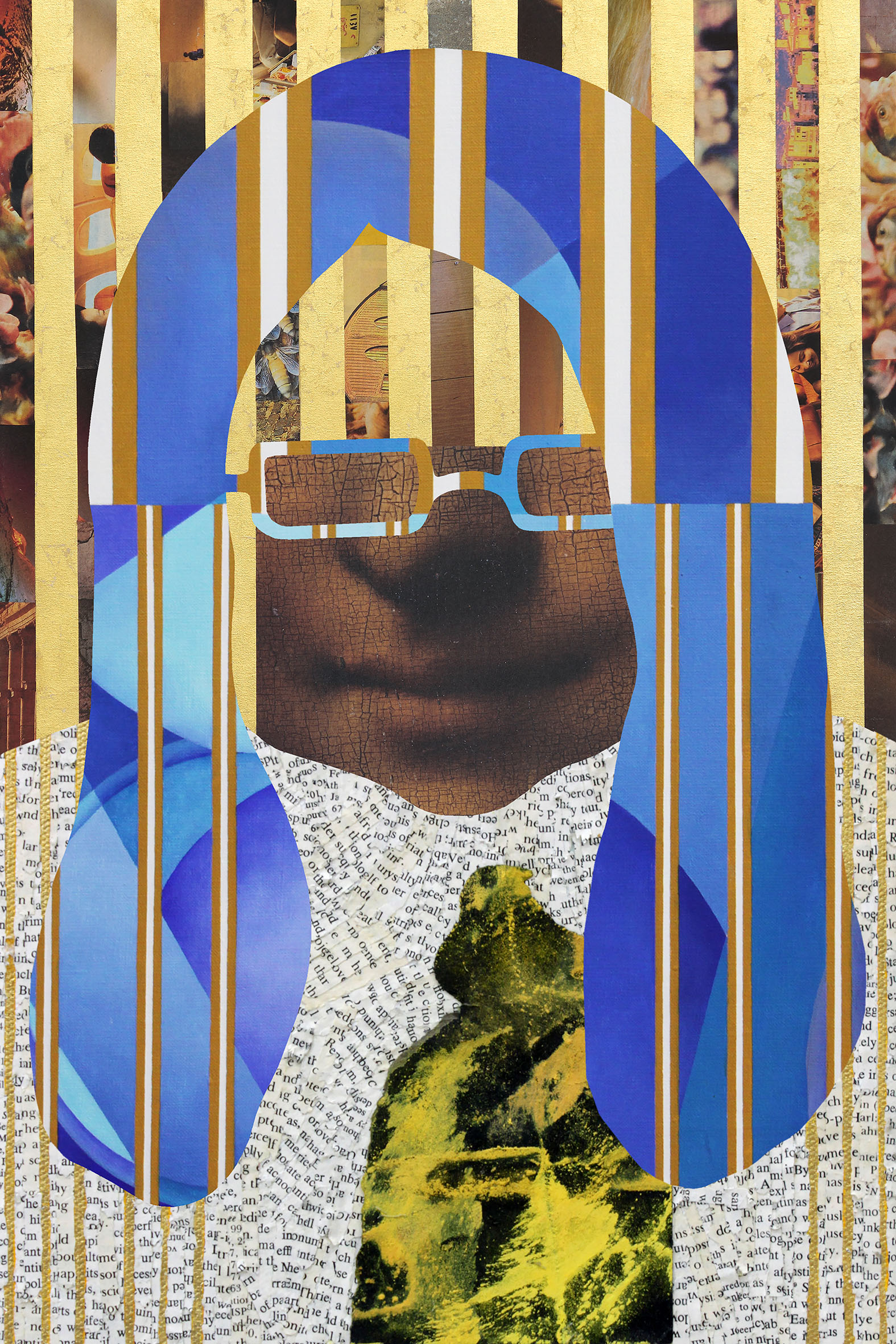

Ostoya’s portraits are based on sketches she made of fellow citizens riding the J line of the New York City Subway system. “It was striking how the demographic changed along the route,” she muses, “since the train went from Wall Street through Chinatown and the Lower East Side in Manhattan to Williamsburg, Bushwick, all the way to JFK Airport and the Jamaica stop in Brooklyn.” Ostoya liked the energy of her drawings and the variety of people represented—a microcosm of our larger common life—but wanted to do something more with them. She decided “to follow the sketches’ outlines to compose photomontages,” using reproductions of her own paintings and collages from the preceding decade. They are, in effect, fragmented forms of Mouffe’s ideas. Each image foregrounds a central but abstracted figure and constitutes a moving testament to the ways Ostoya is moved by Mouffe’s words and aspires, in turn, to move us.

Conventional in form, Mouffe’s original essay is a succinct sixteen pages. Ostoya cuts it up, spreads it out, and extends it, making it a book-length piece, leaving scanner shadows intact. In other words, the copy is a self-consciously lo-fi reproduction—Ostoya’s translation rendered visual. In her hands, the theoretical essay becomes a veritable conceptual poem (what she calls “vertical compositions”), replete with enjambments and caesuras, offering it a different tone and tenor. She “followed an imaginary reader’s voice” to decide just how to truncate and separate Mouffe’s prose lines, giving them more time and space—breathing room that encourages heightened attention and intimacy. It’s a taking apart that builds anew.

Here, most lines are a mere word or two long, and some pages contain only a line or two, variously spaced. In places, full pages remain blank. Still others reproduce one simple line—not a line made up of words, but the black horizontal line that in Mouffe’s original appears under the essay’s page numbers or above her footnotes. Ostoya isolates such lines and turns them, too, refusing to play it straight. The slant becomes a rich visual pun, the manifestation of a different perspective, a new angle. It’s a reminder to look again and askance. The verbal and visual play radiates in multiple directions. It asks questions.

Intriguingly, while Ostoya arranges Mouffe’s essay otherwise, she omits nothing but page numbers, frustrating traditional citational methods in the process. She leaves Mouffe’s original word order and thus the overall argument intact. That said, the very act of formally translating Mouffe’s text is inherently interpretive. Ostoya alters our experience of it, its affect, by transforming the look, feel, and rhythm of the words and adding her visually dense portraits throughout. She asserts that the “only rule I followed was to put the ‘I’ and its derivatives on top of a page. These are the pages with colorful images.”

Every portrait and textual collage is an exploration of “the stakes of democracy,” and an invitation to consider their implications and revelations.

The first colorful image we encounter (it’s also the book’s cover image) appears on the left-hand side of a spread with a radically enjambed line on the right: “I / have / been / concerned / with / what.” Next to Ostoya’s portrait, we might read this line and its exaggerated caesuras as a question: who is “I” (Mouffe? Ostoya? both? neither?) and with what is “I” concerned? We might well read this line as I have been concerned with what is happening on the political left—arguably the animating concern of this project. (Notably, all the portraits appear on the left-hand side of page spreads.) Looking to the left, there’s a subtle yet discernible interrogative in the portrait itself, a curved line around the primary subject punctuated at its collar. In the background, there are archival photographs of quite serious people (all men, save one), but the most powerful photographic impression is that central eye (coded female) with its direct stare. The homonymic relation between visual “eye” and textual “I” remains a question of perspective.

The “eye” is ripe with interpretative potential. We might read it as a kind of disturbing surveillance or, instead, as an invitation to connect—to be in relation, to look more intimately and more deeply. It might also function as confrontation or challenge: Can you see and acknowledge the “other”? What separates and connects “I” and “you”? Can you resist turning away, despite potential antagonism and discomfort? In conjunction with Ostoya’s spatial extension of the original essay, such visual motifs prolong readerly attention and engagement. It’s also a testament to the care, respect, and intimacy necessary for political engagement.

Every portrait and textual collage is an exploration of, among other things, “the stakes of democracy,” and an invitation to consider their implications and revelations. Ostoya’s portrait collages are made up of many things—including images of others—in various configurations. No two look alike. Her subjects are not sovereign, necessarily existing in relation with others. There is a constant interplay—or irreducible tension—between the individual and collective, self and other, women and men, friend and enemy, mind and body, visible and invisible, literal and figurative, (photo)realism and abstractionism, past and present, presence and absence, interior and exterior, black-and-white versus color, hard lines and supple curves, access and denial, political left and right, “us” and “them.” The portraits are Mouffe’s ideal of an anti-essentialist “agonistic pluralism” aestheticized, illustrations of a “multiplicity of positions in society, some of which can never be reconciled,” and a strong assertion that they can “coexist without violence.”

Words and images are in dynamic dialogue throughout Politics & Passions; fittingly, the book’s concluding section comprises a substantive, sustained conversation between Mouffe and Ostoya marked by energy, curiosity and, it must be said, passion. It’s a welcome coda. Each is against apathy, easy answers, and consensus politics; each believes in resistance rather than resignation, and the abiding potential of change—there are always ways to fight against the hierarchical and hegemonic powers that be. They wonder, wander, and riff with each other on topics ranging from the past forty years of political terrain (in various countries) to our current contexts (including the pandemic), to the value and purpose of art, to the need for “more experimental thinking.”

Mouffe describes herself as an “intellectual activist,” and we might likewise consider Ostoya an artistic activist. When Mouffe asks Ostoya how she would like her art to impact people, Ostoya identifies the dignity and power we embody, if only we can see clearly and passionately enough to use them. She hopes her art might make us “imagine other possibilities,” she says. “And when I say my art is a tool, I mean I hope it could help diminish violence and suffering, since I do believe that art can inspire people to realize who they are and who they want to be.” They agree this is especially crucial in the profound “social, economic and ecological” crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. As Mouffe asserts, we need “to awaken positive feelings and mobilise affects” as “a step towards the radicalisation of democracy.”

Politics & Passions was published by MACK in July 2021.