Sabiha Çimen, Quran School students having fun with a pink smoke bomb at a picnic event, Istanbul, Turkey, 2017

© Sabiha Çimen/Magnum Photos

Chris Boot: Earlier this year, you started a website for photography debates and as a meeting place for ideas, Truth in Photography, which has just launched its second edition. Can you start by telling me why the focus on truth?

Alan Govenar: Issues of truth are more pressing than ever. We’re all looking for truth, particularly as it relates to current events, news, photography. The possibilities for manipulation of the truth have never been greater, given the technological advances over the last decades. Truth in photography is a question, not an answer. Truth in photography is a perception. It’s a feeling. In many ways, it’s intangible.

Boot: It’s clear from the second edition that the arguments and issues are evolving. It ranges from Nigel Poor’s work within the prison system, The San Quentin Project, that began as a feature in the “Prison Nation” issue of Aperture magazine and is now a book, published by Aperture.

There’s a piece about the Bronx Documentary Center, another about the girls of Quran schools by the Magnum photographer Sabiha Ҫimen.

Govenar: She is one of the most fascinating new contributors. What’s particularly interesting is that she is a young photographer, and this work related to the Quran schools is her most personal. She told me that in these photographs, she sees herself. She attended Quran schools. Her sisters attended Quran schools. And what she has been striving to depict in her photographs is a sense of what the girls are experiencing, how they manifest their inner lives. Growing up, she was told by her mother that the headscarf was liberating, that if she wore a headscarf, then she could mix in the world. But her mother was also committed to her getting a secular education. So, for her to go into the Quran schools—not only is she in some sense realizing a truth about herself, but she’s also looking at how these girls dress essentially the same, how they engage in group activities, what their fantasies are.

© Sabiha Çimen/Magnum Photos

Boot: Her text is incredibly powerful. It’s probably relevant to mention that she’s Turkish and grew up in Istanbul, so she’s right at that crossroads of the secular West and the Muslim East. What she has to say about her adoption of the scarf and how that changed her and made different kinds of photographs possible is a moving piece of writing in addition to the photographs.

Her work, in a way, is both core to a kind of changing set of values in photography, which, judging by the content of Truth in Photography, you’re thinking about and monitoring. And clearly, the Me Too and Black Lives Matter movements have had an enormous impact on the field. Do you see a new ethics for photography emerging, and if so, how would you describe the contours of that?

Govenar: I think the awareness, the consciousness, of ethics in photography have become more apparent, more visible. Photographers are having to discuss ethics, perhaps in a way that they have not before. But historically, for me, the ethics of photography are never neutral. Photographers and photography take a position, a point of view that’s inherent to the framing in which the images are made. This has always been an issue. Issues of truth are time-honored and time-debated, maybe time-disregarded. But we now face this floodgate of images daily. We have to somehow try to make sense of them.

Boot: It does feel like the words “cultural revolution,” as they apply to what’s happened in the last few years and particularly last year, have real meaning here. Would you agree with that?

Govenar: I would. But I think in a larger sense, it’s not only those issues. It’s the systemic issues, because so much of the production of photography, particularly as it relates to photojournalism, is driven by magazine editors, newspaper editors, online news editors.

And then the other spectrum is fine art photography—or what we like to think of as fine art photography, when in fact, for me, it’s a kind of artificial hierarchy that emerges in photography beginning with Stieglitz. While photography is perhaps, intrinsically, the most democratic of all art forms—anyone can make a photograph if you have a camera, and it’s become easier—but photographs are not considered equal. The technical and aesthetic criteria by which we judge them is also part of the issue: How do we see the image? How do we feel the image?

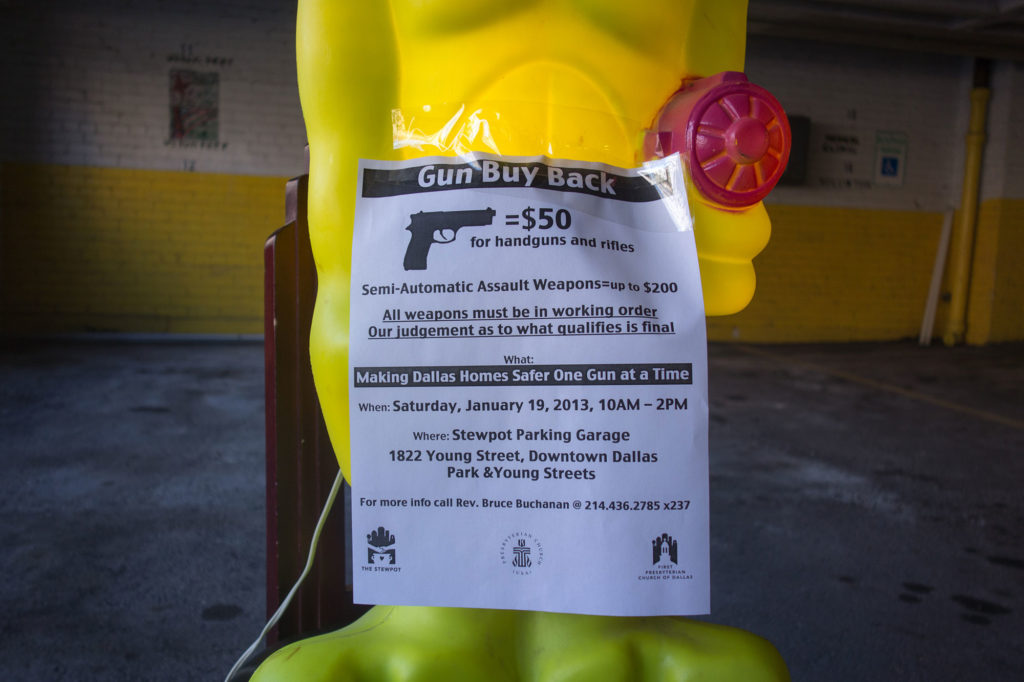

Those are the issues that are not often discussed. But then how are the subjects that photographers focus on prioritized? One of the areas in the spring edition that we introduced is this idea of the struggle for gun control. I was very surprised to find, in searching the Magnum photo archive, that there were no photographs ever made of gun buybacks, which have been happening for decades in the United States and in other places around the world. We’re featuring a portfolio of work by Alessandra Sanguinetti of the March for Our Lives protests. She photographed one of these demonstrations. They were held all over the country.

© Alessandra Sanguinetti/Magnum Photos

Boot: You’re identifying a gap in the perspective. I mean, it does seem like Magnum, and not Magnum alone, but a generation of photographers who perhaps have taken advantage of, let’s call it photographer’s privilege—they could go anywhere and had the privilege of viewing others the way that they were not viewed. That was, in a sense, the essence of photography for many years. These quixotic individuals who could adapt and fit in and record without necessarily having a responsibility to their subjects—although I do very vividly recall a conversation with Philip Jones Griffiths several years ago, where he discounted any photographs that were made without the implicit consent of the subjects, i.e. that his idea of photography was rooted in the sense of serving the subject rather than just catching the subject.

But that generation of photographers is deeply challenged by this new environment. Magazines and the media generally have to think differently about who they commission and what viewpoints they adopt, with much more attention paid to the subjects, paid to whom the subjects would wish to be recorded by, obviously with a drive towards more inclusivity and balance in their commissioning practices. Is that something you encounter in your work, this sense of the older generation being profoundly challenged by new thinking?

Govenar: Consent and context are critical in the making of photography, in the publishing of photography, in the exhibition of photography and its presentation in various media. It’s always been a concern of mine. I founded Documentary Arts in 1985 to have a holistic approach, a way of seeing the still photograph as important, but also to focus on not only, how an individual image can become iconic, but on issues of context and the ways we can contextualize the image in different media. To really understand what is happening around us or what we are experiencing, we need to also listen to audio, or see film, or video. If there is truth in photography, it’s in the multitude of perspectives. And that isn’t limited to the factual media. Sometimes it’s in the interpretation. Sometimes there’s more truth in fiction, than in what appears to be factual. Ultimately, truth in photography is intangible, it’s about what we sense, what we identify with, or perhaps know through the realm of experience.

© Fanta Diop/Bronx Documentary Center

Boot: One of the things that occurs to me about the future of photography is, well, take New York City, for example. You’re out and about with your camera in New York. Subjects are not passive. There are rules of respect and consent that go with the territory of a highly empowered society, let’s call it that. Whereas the history of photography is marked by colonialism and photography served colonial purposes., While much of that has changed, there has been a different attitude to subjects and consent from photographers working in places where people don’t have a voice in the same way.

It occurs to me now that you have to treat every subject the way you would your mother, your brother, another New Yorker. You just can’t have a hierarchy depending on where you are photographing.

Govenar: Part of what we’re trying to do is present the work of professional photographers side by side with the work of community-based photographers and vernacular photography. In the 1980s, I started writing about this concept of community photography. Until that point, discussions of community photography were largely focused on content, what was in the picture. What I was interested in was the process through which these photographs were made. I had received a commission from the Dallas Museum of Art to create a project called Living Texas Blues, and, and at that time, there was a two-volume history of Texas photography being published by Texas Monthly Press. And there was not a single African American photographer represented. When I talked to the curators who were both at major institutions in the state, they said, “Well, we only had time to work with existing collections, and we couldn’t identify any known African American photographers in an existing collection.”

That was in 1985. And that’s when I founded Documentary Arts. Our first major project was focused on African American photography. It’s when I went to New York to meet with Cornell Capa to discuss some of these issues with him. He introduced me to Deborah Willis, who’s been a colleague for decades and who’s been very enthusiastic about the work of Documentary Arts.

In 1995, my wife Kaleta Doolin and I founded the Texas African American Photography Archive. In the first edition of Truth in Photography, we featured a selection from the sixty thousand images that we collected and form the core corpus of this archive. But the bigger point here is that we have worked to present community photographers, who were actively involved in their communities. On the Truth in Photography website, you can hear the voices of the photographers and watch video of people in their communities talking about their work. So, in a sense, what’s being advocated today, which is consent, context, and transparency about the nature of the interaction between the photographer and his or her subjects, the collaborative portrait—all very important ideas—this is the way community photographers have historically worked.

I organized and curated an exhibition on Alonzo Jordan for the International Center of Photography that opened in 2011. He was a barber in the town of Jasper, Texas. His barber shop, when he wasn’t cutting hair, was his studio. His living room was his studio. And he worked in a seventy-mile radius around Jasper in little towns, making photographs. The photograph had greater significance than just what was in it, what the subject was. It was the way in which the subject was depicted and portrayed.

© Alan Govenar

Boot: And the way that image played a role in family lives, individual lives, community lives.

Govenar: And the self-esteem of the subjects. So, when we’re talking today about a new ethics that needs to address these same issues, I think what we’re also talking about is the need to broaden our knowledge of the history of photography.

When the book on Alonzo Jordan was published by Steidl in 2011, it inserted someone who was a total no-name in the history of photography into the canon of photography When we talk about the new ethics, we have to include a reassessment of history going back even into the nineteenth century.

Photobooks have become so important in our world today as a mechanism for transmitting and communicating the work of exciting new photographers but also reassessing historical images. Aperture magazine has also gone in that direction. What we’re doing on the Truth in Photography platform, is, in part, reprinting older articles. For example, in the spring edition, in citizen journalism, we’re reprinting an Aperture magazine article on polling places, for which people were asked to photograph the places where they vote. It’s a wonderful article. And it’s a way to take photographs that were made in the past and present them in the new context. Because we see them differently today. Context defines our perception.

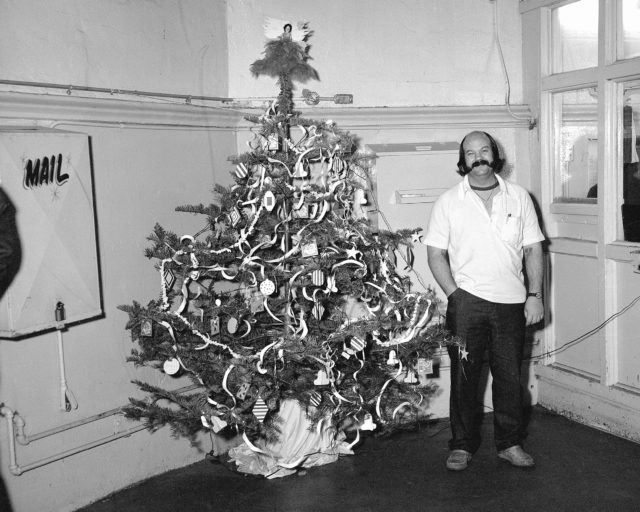

![Volunteers who sang and delivered Xmas packages to SHU [Secure Housing Units], December 25, 1975](https://aperture.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NP_016_Mapping-HR-1024x666.jpg)

© Tommy Shakur Ross. Archival image courtesy San Quentin State Prison

Boot: It’s very interesting you should talk about community photography. As it happens, my first job in photography was in London in the 1980s within a community arts and photography movement that was all about empowerment, empowering the subject, empowering people to tell their own stories and photographs as an alternative to the objectification of a professional media. Have you looked at the community photography movement in Britain in the 1980s?

Govenar: Very much so. When I started writing about community photography, one of the photographers whose work I admired was Val Wilmer, whom I’m sure you knew.

Boot: Yes.

Govenar: Val introduced me to exactly what you were talking about. She was immediately interested in what I was starting to write and think about. And one of the first publications—and probably the first outside the United States—of one of these images that I was working with was in that magazine Ten.8, which was such an important photographic journal. Through Val, I was introduced to the Photographers’ Gallery. I didn’t know that much about it, but I was definitely in tune with that. Going to London in the 1980s—you and I didn’t know each other, but we were focused on some of the same issues. It was also around the same time that I met Simon Njami, who was publishing his journal Revue Noire and publishing little photobooks about then-unknown African photographers who were essentially community photographers in different parts of Africa.

There were other parallels. Certainly, the work that was being done by African American community photographers paralleled work that was being done in Latino and Jewish communities. In a sense, by understanding community photography, we had a lens to better understand, for example, the work of Roman Vishniac and others.

Part of it is that we’re searching for the factual in photography because the way photography has evolved is that we’ve tended to attribute higher value to images that aren’t factual, not only as commodities in the art world and artworks. So, the image that is the faux reality may be worth more from a monetary standpoint than the image of something that is factual and accurate.

But it’s interesting to see how things are turning now. In my interview with Clément Chéroux, he talked about how the need for us to know what is factual and accurate is increasingly more important to us, because there’s so much that is false. Sadly, some photographs of fictional realities have created the groundwork for what we now call misinformation. Ten years ago, it was called art. Maybe it’s still called art, and maybe, it should be called something else.

Boot: Alan, I congratulate you on the work you’ve done over your lifetime of expanding the understanding of photography and what you’re doing today with Documentary Arts and with Truth in Photography. Thank you for sharing your thoughts with Aperture.