A New Look at Walker Evans

In her recent book, Svetlana Alpers explores the cultural figures that influenced Evans’s renowned photographs.

Walker Evans, Independence Day, Terra Alta, West Virginia, 1935

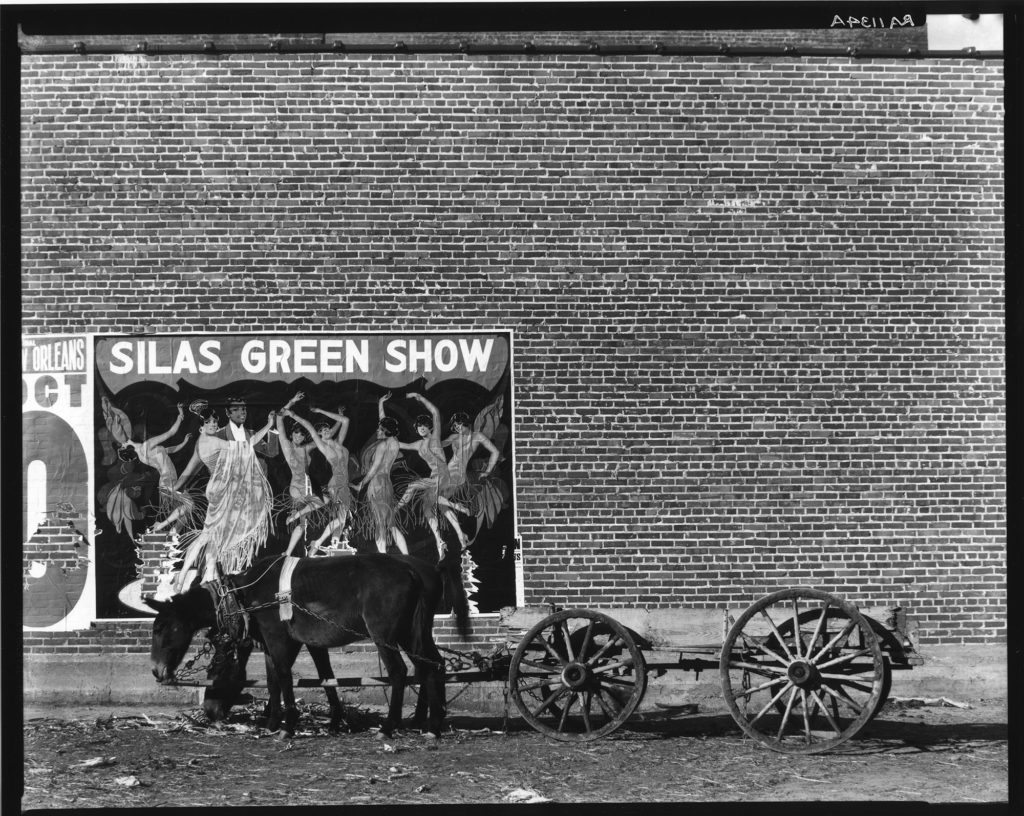

The title of Walker Evans’s 1938 book, American Photographs, provokes because it is both assertive and ambiguous. How could a photographer, then only a decade into his career, claim such simple, self-assured authority? (It’s not Some American Photographs.) How does he define American? (The book includes two photographs taken in Cuba.) What, for him, constitutes a worthy subject to photograph? From the evidence he presented in its pages, the answer is, first, buildings (both exteriors and interiors), then people, then . . . not much else. Landscapes, still lifes, and other established pictorial genres appear to be of only fleeting interest to him. Despite this limited purview, when the pictures are read in sequence it can feel like he accounted for everything.

The title—and, of course, the stunning photographic achievement the book reveals—has perennially motivated critics to place Evans alongside others, mostly modernist artists and writers, in their attempts to define the contours of a uniquely American culture. Lincoln Kirstein, writing in the essay printed at the end of American Photographs, cites T. S. Eliot, John Dos Passos, Marianne Moore, and Ernest Hemingway. Alongside Eliot, historian Alan Trachtenberg mentions Henry James and William Carlos Williams. Now comes the art historian Svetlana Alpers who, in her recent book Walker Evans: Starting from Scratch (Princeton University Press, 2020), a fresh consideration of Evans’s pictures, adds to this list both E. E. Cummings and Elizabeth Bishop. But Alpers is unusual in that, unlike Kirstein, Trachtenberg, and other Evans scholars who wrote often about various American subjects, she is an art historian whose long and celebrated career has focused on European painting. As a subtitle, Starting from Scratch describes not only what she believes Evans was doing but also, to some extent, her own enterprise.

One of several departures that give Alpers her premise of discovery and new beginnings is Evans’s decampment to France in 1926 and 1927. During this period, he gave up the literary career he had dreamed of and made his first creative pictures. The infamous Paris café Les Deux Magots, he later said, gave him “license to stare.” Evans may have set down his pen and picked up a camera, but Alpers is quick and right to insist that literature was more important to Evans than other forms of visual art, even photography. Her detailed explanation of his connection to the tradition of French literary realism is perhaps this book’s most rewarding contribution to the vast literature on Evans. As she succinctly puts it, the budding young photographer “admired Flaubert for his method and aesthetic, but he admired Baudelaire for his spirit.”

Alpers proceeds from the beginning of Evans’s career because her desire is to follow the making of the photographs rather than Evans’s editing of them or their many interpretations. She goes so far as to claim that the order in which he took his pictures is more “significant” than the sequence he later created for American Photographs: “The prior sequence is the sequence at work—let’s call it Evans’s working sequence. It was an activity, not a plan, which is hard to reconstruct even when one is aware that it is there.”

What results from this vantage point is neither full-fledged biography nor concentrated critical study, but rather an engaging series of case studies: of his month in Cuba in 1933, say, or of his famous 1964 lecture on the “lyric documentary” at Yale. More psychological readings come in chapters on Evans’s Subway Portraits, the making of which provoked in him a “tense relationship between submission and aggression,” and on his late Polaroids and collecting habits, which are “marked less by the expectation of creation to come, than by an acceptance of what is lost.”

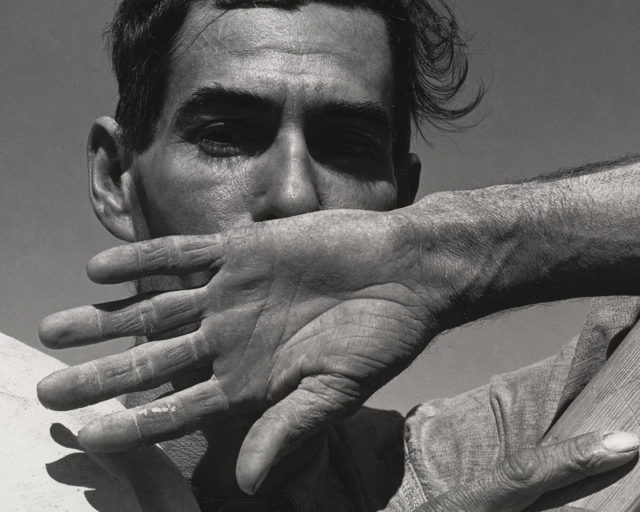

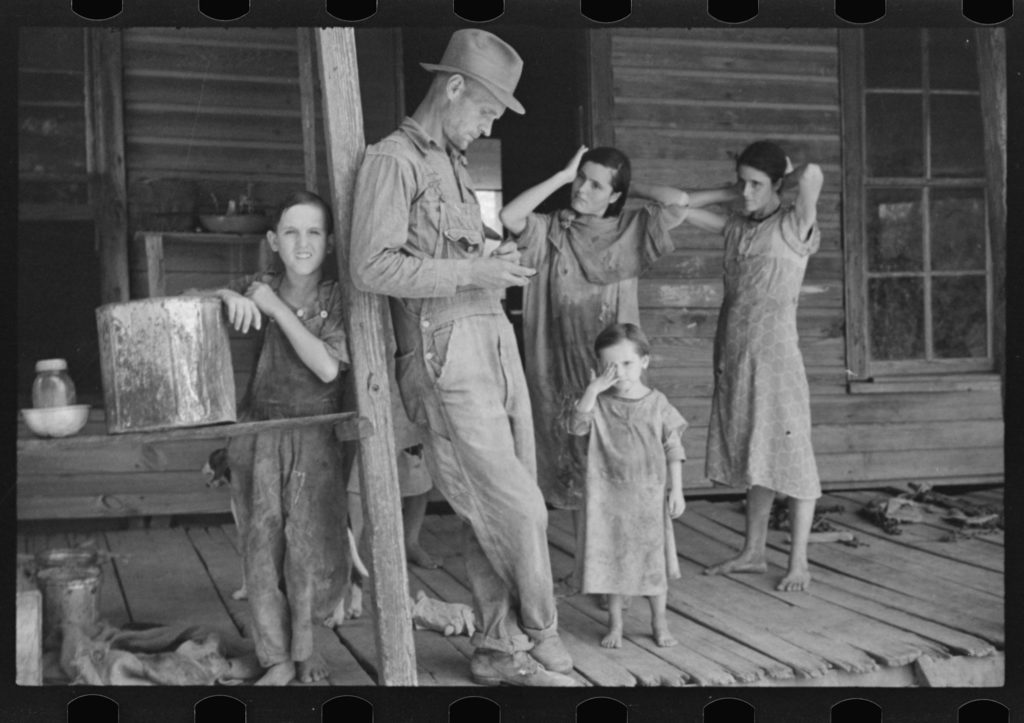

But what no one interested in Evans can escape are the rich, complicated, deadpan, yet astonishing pictures he made in the American South during the mid-1930s. Some were taken while he chafed under the instructions of Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration, others while on a magazine assignment with the writer James Agee. All were made, Alpers asserts, in the wake of the “long Civil War more than the immediate presence of the Great Depression.” This seems right to me, not least because Evans chose to photograph in towns that we know, like Vicksburg, Mississippi, because their names are often associated with battles, and because he didn’t shy away from photographing statues of Confederate leaders.

One of the enigmas of this creative outpouring, however, is what Evans thought his work was saying. Late in life, in formal interviews and informal public conversations, he studiously avoided ascribing political intent or meaning to these Southern photographs. Alpers leans heavily upon these statements, referring repeatedly to certain ones throughout the book. Writing of Evans’s interest in the South, she says, “The answer is not that he was campaigning for better treatment of anyone, but that he was looking, and looking widely. Just how widely has been overlooked or, if noticed, not spoken of.”

Not “campaigning” is itself a political act, and I wish that Alpers had “spoken of” his evasions more. What did it mean for Evans, commenting during an era of racial violence and urban unrest, to disavow the politics of the earlier moment he was photographing—often on assignment for a branch of the federal government? Rahel Aima, writing about Starting from Scratch in The Nation, has criticized Alpers’s analysis of race as “often clueless.” When Alpers notes that “being damaged . . . was historically already the state of the nation,” I, too, wished for her to offer an explicit acknowledgement that the institution of slavery caused—and white supremacy continues to cause—such damage. At one point, she claims, “Evans saw truly what had gone into the making of the south.” But a paragraph earlier she writes, “Evans memorializes the South in its complexity, but he cannot be said to have recognized its demons.”

But one thing I believe is that the South, including its demons, is America just as much, if not more, than the Puritan heritage of the North. Puritan is the word Kirstein uses to describe Evans’s eye. An insistence on Evans’s eye, and what it could see, runs through Alpers’s book. On page one she notes, “Instead of the camera, it was the eye [Evans] spoke of as the major thing for him in photography.”

All photographs courtesy the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Alpers’s references to the Civil War bring another uniquely American name to mind: Ralph Waldo Emerson, who in his 1844 essay “Nature” evocatively describes a transparent eyeball to suggest total absorption in nature. Alpers rightly notes that Evans turned away from the natural world. Nonetheless, unable to get Emerson’s image out of my mind, I returned to “Nature.” In it, I found passages that describe what moves me about Evans’s accomplishment, so long as I transposed Emerson’s descriptions of natural phenomena for the man-made. Consider, with this line, Evans’s ability to create what feels like a panorama of American life despite limiting himself to the Northeast and deep South: “There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet.” Or consider the self-possession of his portrait subjects and the dignifying effect of his frank street views. Though I wish Evans had been more vocal about the racial injustices he saw, and I wish Alpers had acknowledged the shortcomings in the stories he told about his work, the images themselves remain indelible. In Emerson’s words: “To the attentive eye, each moment of the year has its own beauty, and in the same field, it beholds, every hour, a picture which was never seen before and which shall never be seen again.”

Walker Evans: Starting from Scratch was published by Princeton University Press in October 2020.