A Photographer Captures the Experience of Dispossession in Turkey

Cansu Yıldıran’s galvanic images of women activists and queer communities portray the pressures of a society in transition.

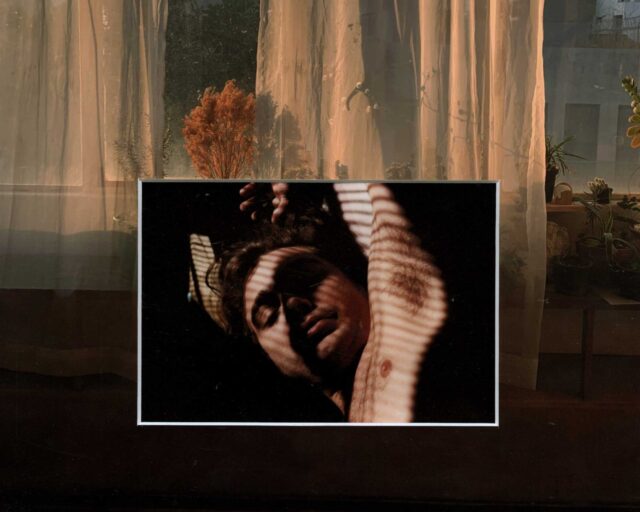

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2018

Cansu Yıldıran was born in 1996 and spent the first seven years of their life in Çaykara, a town in the Kuşmer Highlands, in northern Turkey, on the Black Sea. As a teenager, they found photography, and began taking self-portraits on a smartphone, posing for androgynous images, savoring the medium’s genderqueer potential. They enrolled in photography school in Istanbul and purchased a digital SLR, a Fujifilm, using their mother’s credit card without her knowledge. (This caused a fuss, but their mother said she’s glad they stole the card.) At age seventeen, Yıldıran began shooting the images that would form two ongoing series, The Dispossessed and The Shelter.

Yıldıran’s images are polyphonic; their projects overlap. Many photographs are rich with autoethnographic elements. The Dispossessed contains dimly lit scenes captured in the Black Sea mountains and valleys of their ancestry. In darkness, a flashlight exposes a rural woman or a detail in the landscape with such brightness that it turns them into surfaces with newborn vitality. Yıldıran uses flashlights extensively “because this is what women who work and live in those mountains do.” In one image, a woman appears faceless against a dark background. Yıldıran had instructed her to point the flashlight to her face. “I cherish the performative aspect of photography,” they told me.

Yıldıran spent many summers returning to and taking pictures of Çaykara, or “lower village,” which lies in a V-shaped valley in the Pontic Mountains. Nomadic Turkish tribes, Armenians, and Greek-speaking Christians populated the region for centuries. Traces of its history as part of the Byzantine, Trebizond, and Ottoman Empires remain. In 1915, during the Caucasus Campaign of World War I, the Russian Army invaded. The ensuing decade saw the Ottoman extermination of some three hundred and fifty thousand Pontic Greeks. Today, Çaykara has a population of about twelve thousand.

On their visits, Yıldıran tried to embrace and understand the place. Portraying women and animals that for centuries formed “an alliance of mountain creatures,” they said, was a means of announcing, “We’re here to ponder the memory of our homeland.” Yıldıran joined their mother, aunt, and other relatives as they picked nuts. Taking pictures, walking around, and trying to be helpful proved therapeutic. The fog that covered the view created sublime landscapes. A woman burns fallen leaves; four women pray before lunch; a goat is milked in a barn.

In this fairy-tale land, Yıldıran’s dreamy images capture a historical process of dispossession. Yıldıran’s mother, who studied dentistry before returning to her hometown, couldn’t own a house because of an old custom that says only men could buy property there. “I realized my work was about being guests for life. About the desire to belong to a place but being rejected by it.” (The Kuşmer Highland is deeded to 373 households residing in Çaykara, which prevents people who emigrated from the village from acquiring property.) “For some reason, I’m taking all these depressive, dark, uncanny images amidst so much natural beauty,” they said. “When I looked at my photos, I noticed they’re all sad because of this cloud of dispossession.”

As Yıldıran frequented Çaykara in the mid-2010s, social protests were rocking Turkey and testing the patience of its authoritarian leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Yıldıran skipped class to join protests at Cerattepe, where thousands marched against planned mining activities by cronies of Erdoğan; eventually, because they were failing her coursework, they left college. Women led the charge in these protests against mining: blowing whistles, playing accordions and drums, banging pots and pans. They inspired Yıldıran to spend a month in 2015 tracking, climbing mountains, and photographing local activists, with an eye to “preserve these things and to act as their memory,” they said. “To help me recall how they felt like at the time.”

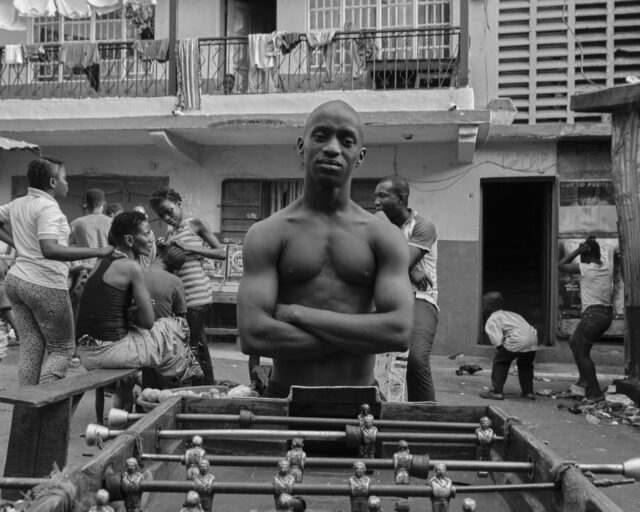

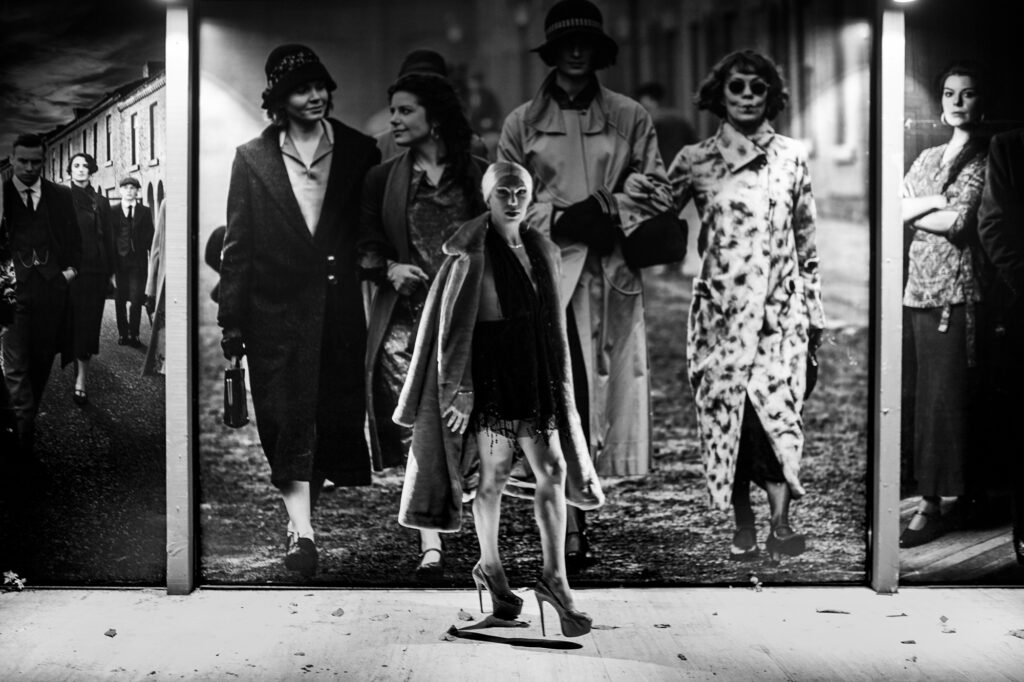

In 2016, Yıldıran won a photography contest, Foto Istanbul. The winning image shows Burçak, a trans woman walking down a street. Her back naked and straight, she stands tall against several people, primarily men, who consider her from a judging distance. Taken during Trans Pride in Istanbul, Yıldıran’s photograph, part of their Shelter series, distills the Turkish government’s intensifying assault on queer communities, known locally as lubunyalar. As efforts to marginalize and criminalize lubunyalar increased, Yıldıran’s interest in documenting the “self-exploration” of Generation Y grew: One man places his head on another’s naked body, where he takes refuge. Shaving each other’s heads, sharing lights for cigarettes, cruising, and dancing, Istanbul’s lubunyalar opened their bodies and hearts to the photographer. Yıldıran shared those images on Instagram, where they had seventeen thousand followers. Then, in 2022, Instagram closed the account. “It was because of the nudes,” said Yıldıran. “That day I learned not to trust Instagram.” Now, they are focused on maintaining an archive and not relying on social media.

For years Yıldıran mainly used a Canon AE-1 and shot their projects on 35mm film. Pressing the shutter once, instead of fifty times, felt right, and they savored “this serenity of waiting for the right image.” The technique empowered hallucinatory frames where characters seem unaware of being filmed but also act out. One example is Yıldıran’s work on Eleni Çavuş, a rifle-wielding Pontic guerrilla, who spent a year in the Nebiyan mountains in Samsun in 1924, before Turkish soldiers captured her in a cave there. Yıldıran’s mother Ayşe Durgun played the role of Eleni. According to legend, a Turkish sergeant had killed Eleni’s child, so she killed him, wore his jacket and gun, and climbed the mountain, from whence her dead body returned. “What happened to the Pontus people is rarely talked about. It’s a really dark history,” said Yıldıran. “It’s not part of the public conversation, and that pisses me off.”

Courtesy Protocinema and Lower Manhattan Cultural Council

Haunt the Present, Yıldıran’s first exhibition in the US—recently presented by the organization Protocinema at the Arts Center on Governor’s Island in New York—riffs on previous series, adding new layers. The photographic-sculptural installation tells a semifictional immigration story, imagining a scenario in which Yıldıran’s mother immigrates to the US from the Black Sea. The show includes images of both places, and for the images of America, Yıldıran spent weeks road-tripping from Michigan to the Pacific Ocean, driving up to ten hours daily, visiting national parks. Istanbul’s lubunyalar were an inspiration: Yıldıran observed how they began immigrating outside Turkey in large volumes over the past decade. “I felt oppressed in Istanbul, and to get away and see all the vast vistas opened me up.” The superimposed images explore the possibility of meshing the Anatolian plateau and the American landscapes and ask whether they can converse.

The intermingled fragments of Yıldıran’s vision will endure: the faces of their mother and aunt in costume, details from historic Pontus photographs, and images of Black Sea women who continue to live under the oppression of a patriarchal regime. Their multilayered compositions create new geographies. “This is why I add volume, cut, and shape my images,” they said. “I build my dreamlands.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.