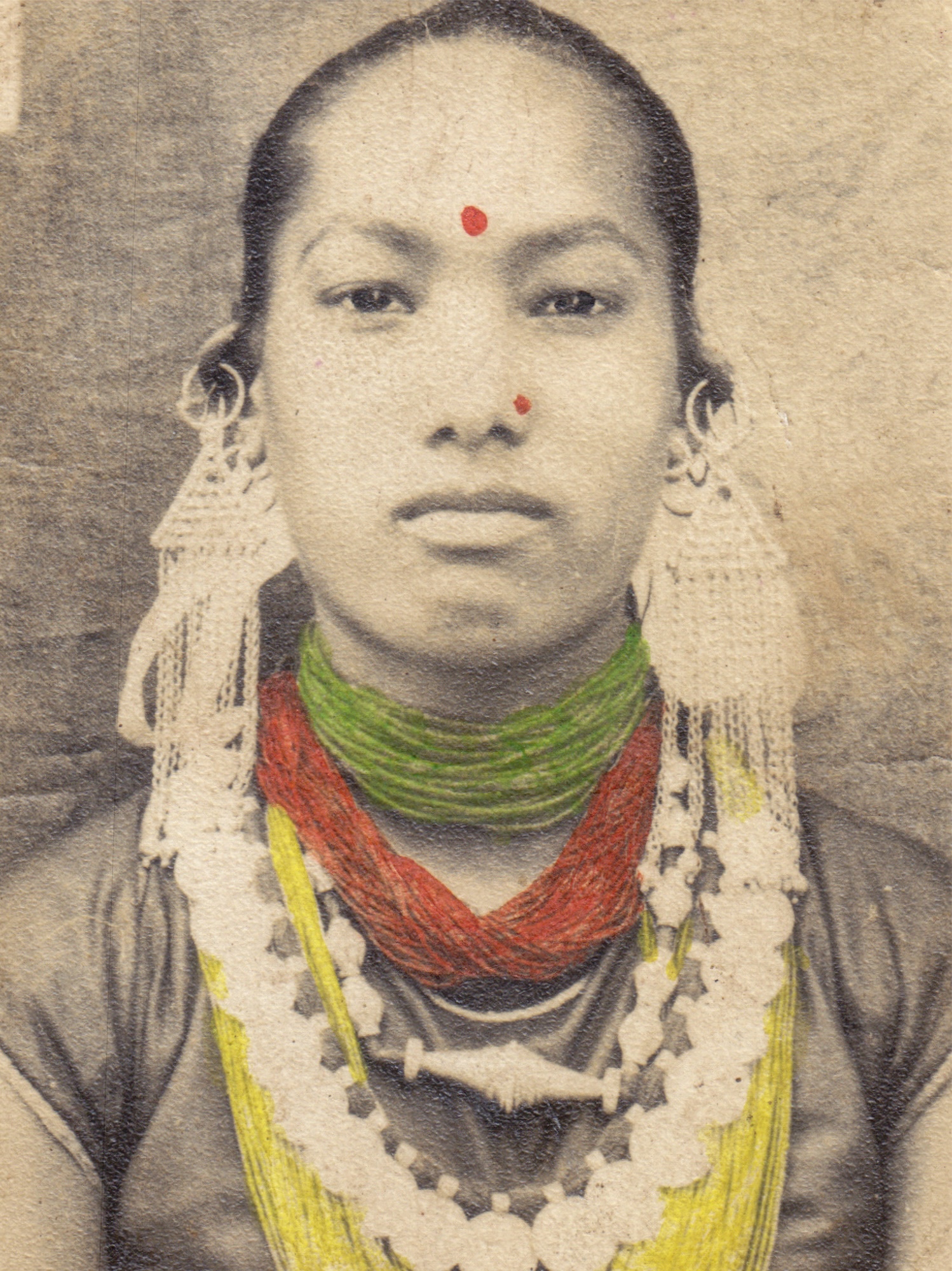

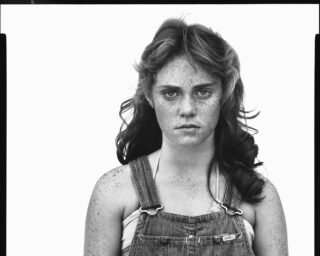

A Tharu woman from Karjahi, Dang, who helped lead a peasants’ revolt against local landlords, 1980

© Premkali Chaudhary Collection

To be absent from history is to be denied possibility. In contemporary Nepal—a former monarchy that has seen a turbulent shift to democratic representation over the last several decades—questions around the public record, and who is and isn’t included, have gained renewed force. For twelve years, the Nepal Picture Library (NPL) has been building an expansive digital archive of the country’s social and cultural life, amassing more than 120,000 photographs from a variety of sources with the aim of creating a collective sense of historical place in Nepali society.

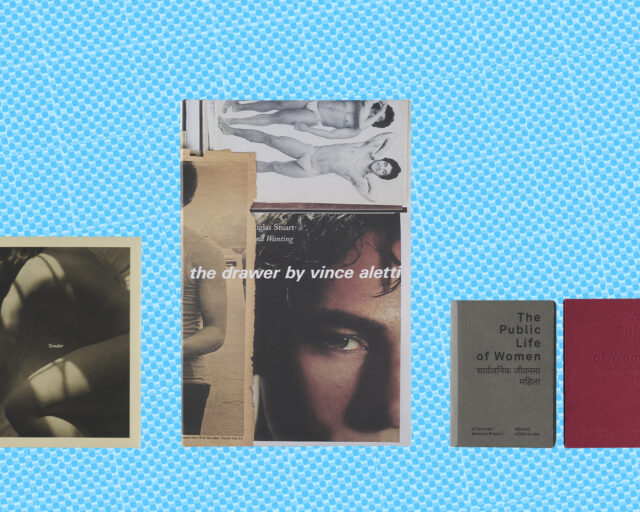

In 2018, drawing from its larger collection, the NPL launched the Feminist Memory Project, an archival effort responding to the need for a comprehensive women’s history in the country. That same year, the vast portions of the archive were presented as an exhibition, titled The Public Life of Women, at Patan Durbar Square in Lalitpur during the 2018 Photo Kathmandu festival. “We want to highlight what the feminist experience has felt like in Nepal,” the curators NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati and Diwas Raja Kc wrote in a statement, and “show how the structures of history that push women into oblivion are in fact contingent and changeable.” In its most recent expression, The Public Life of Women has taken the form of a photobook, published this past October by the NPL’s parent photography platform, photo.circle.

Gurung Kakshapati is the cofounder and director of the Nepal Picture Library, and Raja Kc is its head of research. On the occasion of the launch of The Public Life of Women, which was recently named Photography Catalog of the Year at the 2023 Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards, I spoke with them about the project, the possibilities of their archive, and photography’s relationship to historical memory.

© Sushila Shrestha Collection

Varun Nayar: I want to begin with the role of the photographic archive in Nepal. What do you mean when you call the Feminist Memory Project an “archival campaign”?

NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati: When we set up the Nepal Picture Library in 2011, we’d been working as photo.circle for about five years. I come from a background of storytelling, so I was drawn to the history-making work that the archive does. There’s this strong subjectivity and set of values we’re bringing, saying, “These are important histories to be preserved and documented, be told and retold,” especially to local publics here in Nepal. This idea of an archive being state-run, or in some kind of big, clunky institutional setting that is very static, slow, and not very approachable or accessible—we’re trying to spin that on its head.

Diwas Raja Kc: We’ve done quite a bit of redefining of the concept to be able to do the kind of work we do, and have thought of the archive as something active. The idea of a “campaign” is associated with that way of thinking. It’s about the building of the archive itself—which for us means collecting and cataloging all the photographs we are working on making publicly available—but we also understand that this building is an unfinished process.

We have a double objective for the Feminist Memory Project. One is the repository nature of these photographs, thinking about the longevity of the project, and what can we do to make these materials last for people who come after us. But it’s also equally important that they have an immediate effect on public discourse. We see the archive as really about shaping public memory in Nepal, and we want to have an impact on how the politics around memory are being played. This was more severely felt around ten years ago, after the Maoist insurgency in the late 1990s and early 2000s, then a peace process, the formation of the republic in 2008, and then the reorganizing of the country as federated states, and the demand for new forms of knowledge, new histories, and new ways of thinking about ourselves as people. That’s been the context in which we’ve been working, and that was also the context in which some of these questions about memory were really intensely being felt in public life.

© Anjana Shakya Collection and Binda Pandey Collection

© Bishnu Ojha Collection

Nayar: As its title suggests, The Public Life of Women considers Nepali women’s relationship to the public sphere as politically significant. You’ve also described it as a key feminist strategy. How does the idea of publicness frame your work?

Gurung Kakshapati: In one sense, it’s a basic question of who do you want to reach with this work. If the archive is an active one, then who are we reaching? Of course, as a repository in more traditional ways, an archive is something that serves, say, an academic demographic, or writers, journalists, and so on. But ownership of history—and particularly at this juncture of political and social transformation in Nepal, with this real wish to want to be included in the history of this place—has been something that has driven political participation before, during, and since 2006, which is when officially we had the second People’s Movement and became this federal democratic republic. I think a lot of our work has been shaped as a generational response, to understand ways of life here, ways of organizing ourselves. I think in terms of who we are speaking to, the hope has always been to reach different publics and also think of publics as not just one broad sweeping category but, within that, of layered and nuanced identities and groups.

Raja Kc: The question of publicness is a loaded and multifaceted one. When we were doing the research, we noticed how the journey of becoming a feminist for many women was always associated with this idea of becoming public. There are all these stories about what women were doing to become part of public life and the shaping of the nation as it was going through this tumultuous and fascinating movement towards democracy, and through anti-establishment histories, which are very rich in this country.

When the democratic movement began here in the mid-twentieth century, it made a universal appeal to everyone, including women. I think even when men at the time—back in the 1940s and ’50s—hadn’t quite meant for women to leave their homes and become part of nation-building, a lot of women were interpreting the call of democracy that way, that this actually is beckoning us. That became a way in which many women were talking about their relationship with the public sphere and the nation.

© Saraswati Rai Collection

© Naveen Prakash Jung Shah Collection

Nayar: You’ve catalogued a great deal of material that reflects these political shifts. Does it translate differently between the exhibition and the book?

Raja Kc: With the book, even though it’s full of images, it really asks you to engage both aesthetically and historically. Because of the form itself, and by turning pages, even when you fight against it, you take in the information in a linear format. So I think the narrative-building happens with the form itself, not just with the content of a book. With the exhibition, we focused on the abundance of the archive, and just hitting people with the size of the feminist history. That decision emerged from a context of people repeatedly saying that women don’t have a history or don’t have archives too. We amassed a lot of photographs, and wanted people to feel that volume. The point for us was to say there are archives that you can build and ways to pull out these histories.

Gurung Kakshapati: I’ve been thinking about our work as being on the periphery of mainstream media, on the periphery of the arts world, on the periphery of academic research. We’re not at the center—in more traditional definitions, I suppose—of any of these spaces. That has its pluses and minuses, but it’s actually quite an advantageous place to be too. Because then you can sometimes draw people into this conversation or process in ways where they will enter the work or what you are proposing very unassumingly. People will respond because we’re outsiders or we are familiar enough, but we’re still not dragged down by the baggage necessarily.

© Prativa Subedi Collection

Nayar: I noticed a productive tension between some of the regionally well-known figures you highlight and your emphasis on tracing collaborative networks of exchange and support. What is the significance of collectivity to this history?

Raja Kc: In some ways, this is the primary argument that we’re making, which has been consistent through the years for us. My own sense is that the mode in which feminist politics has been done in the last, let’s say, two decades or so has really valued these ideas of empowerment. And so, I think what feminism has meant in that kind of context is success, and success specifically in the neoliberal definition, because those are the dominant ways that allow for one to succeed and fail.

I think one way of telling history is through profile-building, which is like an index of women who have become successful, [suggesting] that the feminist is one that is success-driven. I think that idea of what a feminist looks like has dominated the world, and it really has also formed the way feminism is practiced here in Nepal. What we noticed looking at a deeper history of women’s movements in Nepal is a desire to belong to a group. To actually, when you step out of the house, have a collective that is not based on your kin relationships or friendships but forms of solidarity that go beyond that. I think these histories are everywhere in the world, and a certain erasure of feminism as a collective experience and longing is something that has been written out in the last twenty years. Those desires are very much there, and they’ve been the framework through which we were looking at our work: what to collect, what to value, what to assemble. It’s really about making an argument about feminism as a collective experience.

© Rambha Poudel Collection

Nayar: There’s a clear sense of relationality across the archive.

Gurung Kakshapati: Yes, such a telling is not possible without the contribution, active participation, and ownership-taking of many people. It’s also about being able to bring together, as a collective repository, an archive of many acts of resistance. For instance, that photograph of two protestors behind bars from the 1960s; another one of the four women who’d been arrested for having attended a protest and then went to a photo studio to mark their day of release; or those portraits of Tharu women from the Karjahi movement in 1980.

In some ways, many of these women only meet in the archive. They might not have lived during the same time, or even known of each other. It has a cumulative impact on me: that it’s taken several generations of women resisting for us to get here. We’ve really tried to be mindful about foregrounding images with lots of people, crowds, masses. It’s not just about individual women. Outside of the domestic thresholds, many women were experiencing collectivity for the first time when they started going to college, school, the workplace, or even a protest. Whenever we feature individual or passport-size photographs in the book, such as from the collection of the Nepali writer Bhagirathi Shrestha, we tried to put many of them in one place. So it does feel like the archive is also a correlation of all of these experiences.

© Bill Hanson, Peace Corps Nepal Photo Project

© Shanta Laxmi Shrestha Collection

Nayar: In a conversation at the end of the book, you both discuss: “Do photographs make people think more historically?” What possibilities do photographs offer this project?

Gurung Kakshapati: Photographs have really been central to a lot of the work we do. We’re thinking visually, and we’re very much producers, but also consumers, of a visual and image culture. If we’re thinking of posterity, of why we’re building this archive, it’s so fifty years later these records and narratives exist. It feels like fifty years later the visual record is what people will feel most familiar with, or people will have most fluency with. And, I mean, in Nepal, photography actually hasn’t had that long of a history, and only a very small segment of society has had access to photography for a considerable amount of time. But regardless of that, it does feel like women were always taking photographs, to give to each other as tokens of friendship, to mark something, to validate something. That’s what I meant by “thinking historically” and what photographs perhaps allow and encourage us to do.

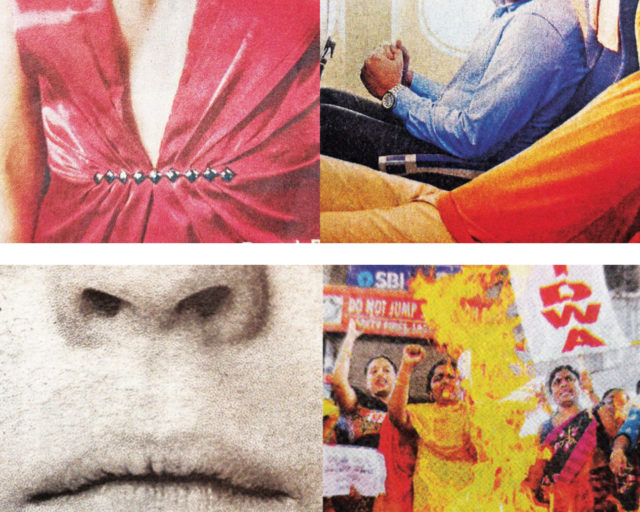

Raja Kc: The way that we work is not just building repositories. We actually also do these projects so that we can put them out as forms of activation and engagement, to the extent that we’re not just collecting; we’re creating narratives as well. We’ve noticed that there are affordances that photographs have that allow for the kind of work we do, for collective storytelling. With this history, we really wanted a democratization of narratives, or to contest the feeling that history is written for certain kinds of people with power.

© Shanta Shrestha Collection

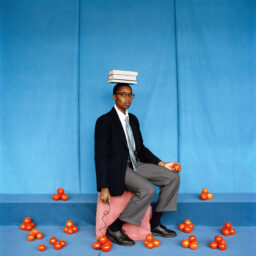

The nature of the photographs we’re really sort of activating is that everyone owns them. These are very familiar genres of photography, and people feel like these are their material. They actually have them in their homes, so the archive itself begins to be defined as something that is not in a state or institutional repository, but actually what we own in our homes, in our personal lives. That is the foundation for telling history, and because photographs were that genre of documentation, I feel like some of the success in the democratizing of the history is fundamentally linked to the thing that a photograph is. We’ve been really thinking about the sensorial or haptic qualities of photographs, or the way they elicit emotions and affects, that the way that you relate to what you’re seeing is based on the triggering of certain kinds of reflections, emotions, and instincts. That to me is really fundamental to what photographs are as artifacts.

The other thing we talk about is the way iconicity and indexicality work in photographs, and how they could be used to tell the story of women’s history as one of presence. Just the sheer force of evidencing presence through photographs really matters in a historical sense. I think photographs allow you a kind of evidencing that is not contestable, and we were really using these affordances and techniques to make an argument about feminist history in Nepal.

Nayar: It’s about seeing this history in full, but also—I imagine—allowing it be seen by more people.

Raja Kc: There are all these photographs that are not properly annotated or documented to be of much use to people who might want to access them. So we’ve been thinking about possibly spending the next year or two to really dedicate our time and commitment to the Feminist Memory Project.

Gurung Kakshapati: We’ve had conversations about the politics of metadata or annotation, like: Who puts in what data or information? Is there a way to do that in a collective or plural sort of way? We’ve talked about the possibility of crowdsourcing annotations and metadata, for example. How possible is that? How do you fact-check the reliability of one person’s memory versus another’s? There are all of these challenges to consider.

© Sukanya Waiba Collection

Nayar: Where does The Public Life of Women go from here?

Gurung Kakshapati: I’ve been thinking a lot about how this book is going to circulate. We’ve been self-publishing for some years now, but the distribution, which then impacts the circulation, is really not easy, as all of us who make books know. We did two thousand copies of this book, and that’s a larger print run than we’ve done before. It feels like we’re going to run out very soon. We want this book to circulate in a different way; at least half of this print run will go out to the 130-plus contributors and the institutions that they’re tied to. We’re also really keen to do free distributions for colleges, schools, and libraries, and also outside of Kathmandu.

Perhaps, several years down the line, we will need a second edition that is a much less expensive paperback version, for example. It feels very experimental each time, and it’s been interesting to revisit a project five years after it was published, for example, and really think about circulation then. There are certain things that we want to be very intentional about in terms of where we want this book to reach. For instance, I think next year, we’re really hoping to travel to different places in Nepal, partner with different groups and organize engagements, and enter or create discursive and civic spaces in different towns and villages. I’m curious to see what something like this book feels like in that kind of milieu and space, as we build the archive, deepen what we know, and create layers of knowledge around these collections. We can’t be everywhere all the time, but we’re thinking about how to work in decentralized ways, build partnerships, and allow for other people to take this work out into the world, and then into their own worlds also. Sometimes if it’s too precious, that defeats the purpose.