A Seven-Volume Photobook Retells the Story of an Ancient Hindu Epic

In his contemporary iteration of the Ramayana, Vasantha Yogananthan’s photographs consider memory, history, and the poetics of daily life.

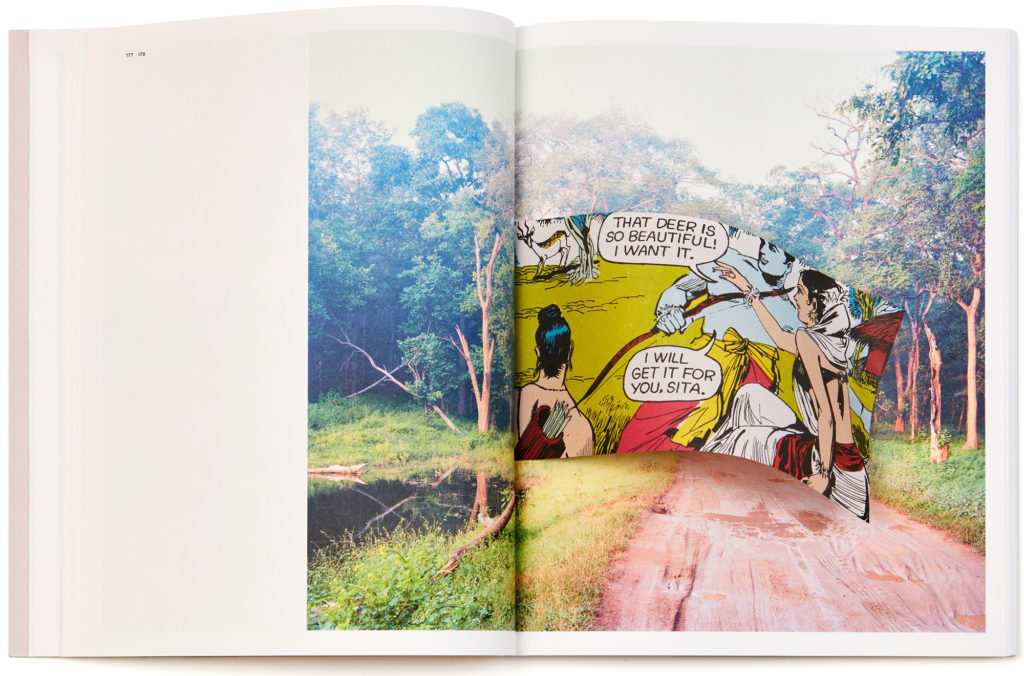

Vasantha Yogananthan, Farewell, Hampi, Karnataka, India, 2016, from Dandaka (Chose Commune, 2018)

“The Ramayana’s over and they want to know whose father Sita is.”

In India’s Hindi-speaking belt, this quip is often used to mock a listener’s inattentiveness—Sita is, in fact, the protagonist Ram’s wife and mother to their sons. Almost two and a half millennia since the Ramayana emerged, supposedly from the mouth of the bard Valmiki, references to it remain as idiomatically current as ever in most Indian languages.

The epic poem charts the journey of divine prince Ram of Ayodhya, his marriage to Mithila’s princess Sita, their exile in the Dandakaranya forest, Sita’s abduction by the Lankan king Ravan, and subsequent rescue by Ram and his allies (including his brother Lakshman and monkey companion Hanuman). In some tellings, the Ramayana ends with Ram and Sita’s return to Ayodhya. In others, Ram’s suspicions regarding Sita’s “purity” while she was Ravan’s prisoner cause her to leave him. She gives birth to and raises their sons on her own, ultimately reuniting the men and returning to the earth from which she is fabled to have sprung. While no summary can do justice to the scope, thematic density, and versional plurality of the Ramayana, what cannot be overstated is the ancient tale’s continued hold on the South and Southeast Asian imagination. So powerful is its influence that in Hindu-majority India it has been pressed into the service of the current government’s fascistic political agenda.

Bottom row, left to right: Dandaka (2018), Howling Winds (2019), Afterlife (2020), Amma (2021)

In a seven-part photobook series titled A Myth of Two Souls (Chose Commune, 2013–21), French photographer Vasantha Yogananthan retraces the geography of the Ramayana to interpret the story as a contemporary lyric in pictures. Composed on color film over an eight-year period and using various camera formats befitting each of the poem’s seven episodes, Yogananthan’s project also involves collage, writing, painting, and performance. Additionally, A Myth of Two Souls includes the work of Jaykumar Shankar, a specialist in the nineteenth-century art of hand-painting photographs; Mahalaxmi and Shantanu Das, painters in the Madhubani folk-art tradition; as well as words by Ramayana scholar Arshia Sattar and writers Anjali Raghbeer and Meena Kandasamy. Interspersed with original images are found photos, press clippings, excerpts from a cult graphic novel series on Indian mythology (the source of Yogananthan’s own introduction to the story), and illustrations from Gita Press, the world’s largest publisher of Hindu religious texts. Through this multimedia assemblage, the series translates a fifth-century BCE narrative about love, war, duty, and honor into the register of twenty-first-century quotidian (Ram plays cricket, for one). It is what the poet A. K. Ramanujan described in his landmark essay “Three Hundred Ramayanas” as “mapping a structure of relations onto another plane.”

A piquant aspect of the translation is Yogananthan’s collaboration with his predominantly small-town subjects—ordinary people whom he either captured in candid poses or persuaded to enact significant scenes from the epic, often with an insouciance undercutting the Ramayana’s premodern theatricality: a woman from Ayodhya with her infant on her lap juxtaposed with a Gita Press illustration of baby Ram and his mother; young jeans-clad couples in Janakpur, Bangalore, and Delhi who channel Ram and Sita falling in love through SMSes and rendezvouses. In Hampi, Ravan and his henchman lie in wait for Sita in a type of van commonly used in Indian movies to signal a kidnapping. A Dhanushkodi fisherwoman gazes at the ocean as though a captive Sita awaiting Ram; a man captioned as Valmiki peers mysteriously from the shadows in Trivandrum. Tapping into the continued resonance of the Ramayana while avoiding Orientalist romanticization, Yogananthan adjusts the aperture between actor and character to allow light in from two thousand years of an evening gone.

Resulting from Yogananthan’s years-long engagement with the communities at these locales, the images recall Gauri Gill’s photographs of rural masquerade. Specifically, they depict a similar mixed-media oscillation between portraiture and tableau vivant, with Yogananthan’s images overlaid with Warli artist Rajesh Vangad’s drawings titled Acts of Appearance (2015–ongoing). Unremarkable objects, everyday locations, and unwitting beasts common on Indian streets indicate characters and events from the Ramayana—roadside monkeys stand in for the simian deity Hanuman, a schoolroom stadiometer evokes Ram’s transition from childhood to manhood, and a ladder leading into a construction-site pit suggests Sita’s disappearance. The use of metaphor, visual rhythm, and allusion allows A Myth of Two Souls to capture the epical quality of the Ramayana, while its success as a photobook lies in its playful narrative arrangements. Yogananthan deploys a range of techniques—cropping and splitting images to effect enjambment, spreading them across facing pages, and superimposing through inserts and tip-ins. The movement of time and place is represented by disparate shots assembled into a unified sequence, such as Ram’s father’s funeral in the series’ third chapter, Exile, or the capture of a single moment in multiple frames—such as when Sita takes the fire test to prove her virtuousness in the sixth chapter, Afterlife.

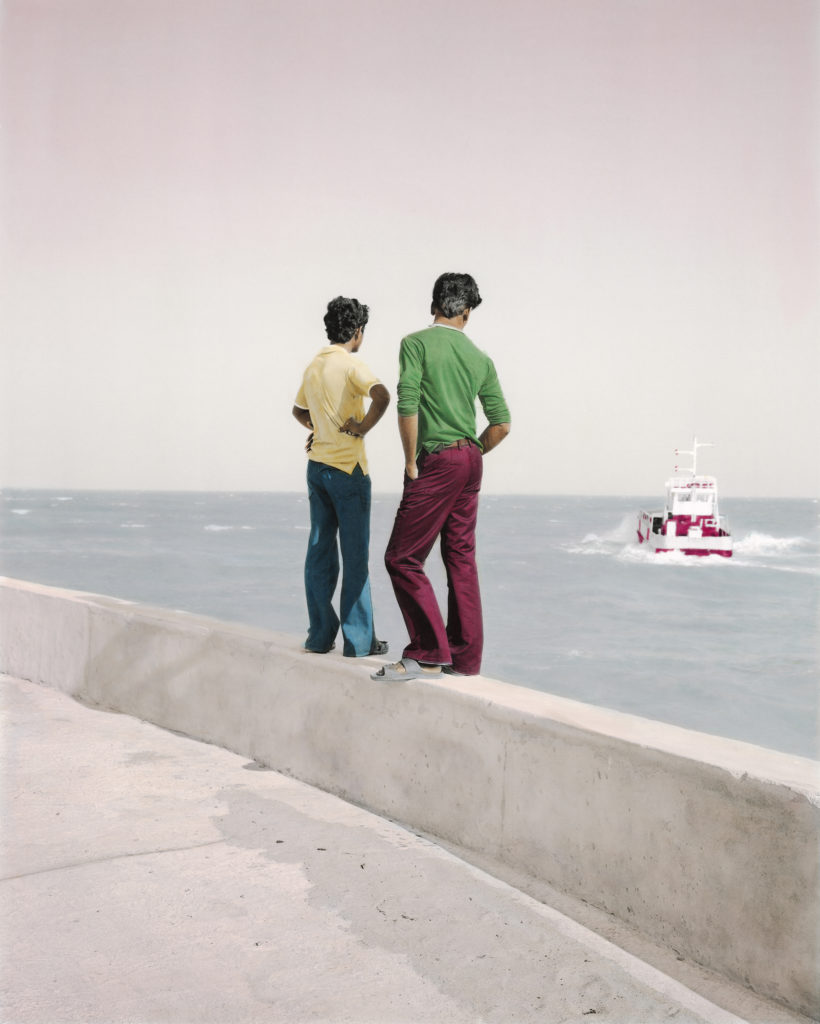

Each book in the series has its own color palette and voice. The design team Kummer & Herrman has created a consistent framework for the books—the trim size for each publication remains the same. Yet every title employs different creative approaches in terms of the binding, paper type, and layout to underscore and support the metamorphosis at work in each chapter of the story. High-resolution and low-saturation shots of riverine, forestal, and urban landscapes similar to those in Rinko Kawauchi’s oneiric Ametsuchi (Aperture, 2013) inundate the first four titles, Early Times, The Promise, Exile, and Dandakaranya. On the other hand, the primary color scheme of the fifth chapter, Howling Winds, made along the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, harks back to Yogananthan’s previous seaside record titled Piémanson (Chose Commune, 2014). In Afterlife, the book of war, Yogananthan used an autofocus camera and flash to shoot intoxicated nocturnal revelers at Rajasthan’s Dusshera festival, who echo soldiers celebrating the victory of Ram’s goodness over Ravan’s evil. In its coverage from Nepal to Sri Lanka, from Tamil Nadu in India’s east to Rajasthan in its west, A Myth of Two Souls straddles documentary, fantasy, and travelogue. Yogananthan’s palimpsestic photographs of people, places, and animals at the sites mentioned in the Ramayana constitute not an album but an atlas of affect. In the manner of an antiquarian pilgrim map transmuting the experiential into the pictorial, these photographs condense memory, history both natural and human, lore, daily life, and contemporary religiosity into a poetics of traversal.

Following a corrective trend of countering the Ramayana’s traditional emphasis on Ram’s perspective, Sita, Lakshman, and Ravan get to tell their story in Yogananthan’s series. For example, the book of the jungle, Dandakaranya, is reminiscent of Jim Goldberg’s work in its diaristic annotations by Lakshman and Ravan. The accompanying texts, all by women, two of whom are not upper-caste Hindu, challenge conservative notions of who gets to narrate and expound upon the Ramayana. To appreciate these authors’ contributions, it is necessary to understand that in present-day India, efforts are on to purge the canon of all but one reading of the Ramayana—a Brahminical one that legitimizes the abuse of a citizenry. There is a strong argument that the Ramayanais part of a syncretic, even problematic cultural heritage rather than a religious one—Jain, Buddhist, Indigenous, Mughal-era Persian versions co-exist alongside critiques from Dalit thinkers. But this understanding is not acceptable to fundamentalist rulers: the old story of Ram has become the basis of a fresh hell.

Purporting to turn India into Ram Rajya (Ram’s kingdom), the country’s far-right ruling establishment and its affiliates weaponize tropes and subtexts in the Ramayana to pit the most powerful class of India’s citizens against its most vulnerable ones. Since the 1980s, there has been a movement to radicalize the Hindu population against oppressed caste groups and minorities, mainly Muslims. The Ram Janmabhoomi (birthplace) campaign, fueled by motorcades across the nation, was aimed at mobilizing support for a temple to replace Ayodhya’s sixteenth-century Babri mosque. In 1992, the mosque was demolished by a Hindutva mob, leading to a lawsuit. In 2019, India’s Supreme Court awarded the disputed land to the Hindu plaintiffs. In 2021, it is thus impossible to receive the Ramayana in any form without acknowledging that the cries of those being lynched, shot, and butchered in pogroms are being drowned out by murderous roars of “Jai Shree Ram!” (“All hail Ram!”).

All images courtesy the artist and Chose Commune

Absent in A Myth of Two Souls is a direct confrontation with the Ramayana’s appropriation to justify state-supported religious barbarity, which might bother secularists. However, it’s possible to view the photobook’s staging of the tension between reality and make-believe, truth and fiction, as a comment on Hindutva propaganda. There is at least one instance when Yogananthan explicitly recognizes the Ramayana’s misuse. In the final episode, Amma, there is a photograph of a wall constructed using bricks embossed with the words “Shree Ram.” The caption reads, “Where A Mosque Once Stood.” In Yogananthan’s narrative, which concludes with a mistreated Sita’s departure from Ram’s rajya forever, the image is a poignant reminder that in an unjust realm, there are no happy endings.

This article originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review, issue 020, under the title “A Myth of Two Souls.”