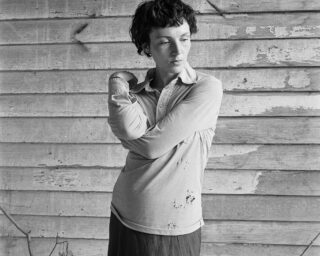

Kunié Sugiura at her studio, New York, 2021

Photographs by Jody Rogac for Aperture

This article originally appeared in Aperture’s spring 2022 issue, “Celebrations.”

In 1811, when the Commissioners’ Plan established the map that was to dictate Manhattan’s development north of Houston Street, city fathers settled on the gridiron as the ideal form not for its Euclidean elegance but for the sake of rank commerce: “Right angled houses are the most cheap to build,” they declared.

Meanwhile, in the city that already existed, streets slouched and coiled like vagabonds, their winding shapes defined by rivers, shorelines, swamps, and large rocks. Among these vintage arteries, Doyers Street, a narrow, two-hundred-foot dogleg angling between the Bowery and Pell Street, is unlike any other. The crime journalist Herbert Asbury, who covered downtown New York, once called it “a crazy street” and said “there has never been any excuse for it.” Turning onto it feels like stumbling into Venice or Kowloon and makes me think of Walter Benjamin’s sentiment in One-Way Street that as soon as we gain our bearings in a city, habit erodes our sense of wonder about it. Somehow, visiting Doyers never stops feeling like the first time because it never stops feeling like being lost.

Recently, I went to the old gray brick building at number 7 and rang the buzzer of Kunié Sugiura, who has lived and worked there in a rough, roomy, fourth- floor loft since 1974, making art that combines photography and painting in ways that confound conventions of both (often involving cameraless photographs and paintings that function more as sculptural objects than as canvases).

Sugiura, seventy-nine, born in Nagoya and raised in Tokyo, moved to the United States in 1963 to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she fell under the sway of one of her professors, Kenneth Josephson, who was at work establishing the terms of what would come to be known as Conceptual photography.

In the early 1970s, Sugiura began layering photographic emulsion, exposed with her Minimalist images of the city.

Sitting at a long worktable in the front of her loft, framed by tall windows overlooking Doyers, Sugiura told me: “I liked photography because photography was not really what it looked like. It’s such a subconscious thing, and you can experiment. Of course, all the other art students at that time completely looked down on us.” She moved to New York in 1967, partly because she sensed it was on the verge of generational upheaval. “And I knew that great social change is when culture happens,” she says. “But mostly, I just thought New York City was a lot of fun. Even going to a deli here was entertainment.”

In the early 1970s, Sugiura began layering photographic emulsion, exposed with her Minimalist images of the city—a storefront, high-rise windows, approaching headlights, the hull of the Staten Island Ferry—on surfaces such as aluminum, wood, and ceramics, until settling on canvas, a nod to the influences of Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, though her work had a quiet poise that resembled neither. As the process developed, she incorporated monochrome or striped painted canvases along with the emulsions, sometimes grouped in wooden armatures that suggested frames but seemed more like elegantly deconstructed Shaker furniture. (The critic Karen Rosenberg once said that Sugiura’s early pieces appeared as if “Walker Evans had teamed up with Anne Truitt.”) Over subsequent decades, she has continued to press restlessly at photography’s boundaries, experimenting with collage, painterly photogram techniques, and landscape-like pigment prints.

Sugiura was featured early on in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1972 Annual Exhibition, curated by James Monte, and her work has appeared in exhibitions over the years at OK Harris, White Columns, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, among many others.

In the early 1970s, after the breakup of a marriage, she met the pioneering dealer Richard Bellamy “who told me he would be my agent—whatever that meant—but he really began to help my career and introduced me to other downtown artists like Neil Jenney.” She began hunting downtown for a space to live and work and chanced on the Doyers Street building, which had once housed the city’s first Chinese-language theater and later became a flophouse before being virtually abandoned in the 1960s. In 1971, the sculptor John Duff claimed the building for artists, making a loft on the top floor, where he remains today, and Sugiura moved in with two artist friends three years later, sharing the building with a Buddhist temple and, for a while, a loft of rowdy Cajuns with connections to Philip Glass’s musical circle and the artist-run restaurant Food, founded by Gordon Matta-Clark.

“This was where I really was first able to have the life of an artist,” she says. “It has sometimes been crazy or hard, but Doyers still feels like a sort of hidden place in the city, even in Chinatown, and the light that comes in my windows is north-east light, which is always beautiful. It’s my home.”