The Accidental PhotoBook

We are at a moment when the community of photobook makers and collectors is expanding rapidly, yet also becoming more insular. We’re ever searching for that handmade artist book created just for the art fair, available in limited copies that are going fast. For many years, the Martin Parr/Gerry Badger Photobook: A History and other books about books have served as a shopping list, bestowing value on the included volumes. Looking back through The Photobook: A History, however, it’s worth remembering that they cast a wide net, including among the shimmer of possibilitys and Sleeping by the Mississippis, mass market books, commercial books, books on food, and propaganda.

It’s been over a decade since the first and second volumes of The Photobook: A History came out, and our community has developed a finely tuned connoisseurship of the artist monograph. For this reason, it is a good time to consider other types of books that use photography, but are not considered photobooks qua photobooks—books that are unlikely to end up on anyone’s yearly top-ten list (and never aimed to). These books are often outside the photobook radar for a variety of reasons, whether they be too idiosyncratic, mass market, or useful (cookbooks, lifestyle, science), but their impact relies heavily on photography. Some of these fall into a guilty-pleasure category, but many, freed from an artist’s agenda and the conventional earmarks of an artist book, present a more direct use of photography and are successful in their own right. In the pages that follow, we have invited photobook aficionados to talk about their favorite niche within the larger universe of photo-illustrated books, and a handful of others to introduce their favorite non-photobook photobook—their own guilty pleasures. In short, this issue will address the unlikely, even accidental, photobook.

My own interest in the category of the accidental photobook began with cookbooks. I bought the 1958 Time Life Picture Cookbook as a joke. Maybe it appealed to me as a reaction against the kinds of photobooks I engage with on a daily basis. From there, I gathered many more cookbooks of a similar ilk—those that had clearly paid as much attention to the staging and photographing of the food as to the presentation of recipes. When the habit grew from a few books on a shelf to an entire bookshelf, I had to admit, it was no longer ironic, but true love. I take more pleasure in a few of these cookbooks than I do with some of the more proper photobooks, many of which are languishing on my shelves in Mylar sleeves. The following are a few of my favorites.

LIFE Magazine ⋅ Time Life Picture Cookbook

Time Inc. ⋅ New York, 1958

Some context is needed to fully appreciate the Time Life Picture Cookbook. Picture cookbooks became popular in postwar America. Women were supposed to get back into the kitchen with new vigor, entertaining needed to start again, national taste and culture had to be re-established. Photographs, particularly of food and feasts, were part of that. The most well-known was the 1950 Betty Crocker Picture Cookbook. It’s bound in a loose-leaf ring binder and chapterized into subject files, so you can quickly get to the Pie section and remove the recipe for cooking. Throughout, decadent color photos burst at the seams with American bounty. Buffet-style spreads are in full force and meant to feed an army of guests: epic picnics and breakfast feasts, rows of frosted cakes and jellyrolls, and salads galore. They are more exuberant than they are appetizing, speaking more to tastefulness (or perhaps the lack thereof) than taste itself. The photos are often set in the home, showing the newest appliances and wares. Here, America presents itself as plentiful during the Cold War, in direct contrast to communism. Despite all the messaging, the book remained a functional cookbook, one that was bought primarily for the recipes and was engineered to be useful. The pictures are a punchy bonus. The tables and counters full of food are aspirational, but still seem achievable.

LIFE Magazine ⋅ Time Life Picture Cookbook

Time Inc. ⋅ New York, 1958

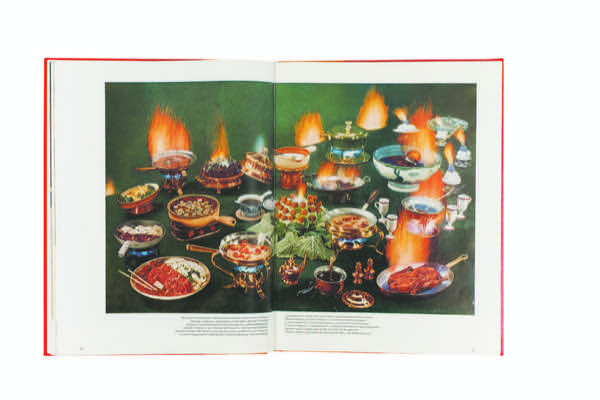

By 1958, the Time Life Picture Cookbook had become decidedly more about the pictures. Sure, it contains lots of recipes, but at fourteen inches tall, this is not the book you’re reaching for in the kitchen. It’s not being bought or produced for the recipes, which are all run together, small. The pictures, however, go across the double-page spreads gloriously, presenting a tableau of food more aligned with still life than with interiors. The production on each shoot is impressive, not accomplishable by any home cook anywhere, with twenty plates of flambé presented in the same shot for the “Flaming Foods” chapter opener or with pineapples frozen into blocks of ice for “Cooking on Ice.” The pictures here are spectacular in the truest sense of the word. They present a wonderful fantasyland of food. Scales and hourglasses appear with perfectly textured Baked Alaskas and Petits Fours in pastel and desert backgrounds, depicting low-calorie and time-saving desserts. The book still operates within lifestyle and taste, but instead of presenting recipes you can accomplish with the help of this book, the Time Life Picture Cookbook is something you would more likely display in your home rather than actually use. Hence, the book is more photobook than recipe book. And the pictures are a joy to look at beyond their nostalgic value. The watermelon on ice with roses is a gorgeous still life that still holds up today; the “Drinks and Hors D’oeuvres” opener could pass as an Irving Penn (it’s by H. I. Williams). Time Life would go on a decade later to publish the Foods of the World Library, which also focused on the photographs—though more documentary in hopes of creating an armchair travel experience of culture through food.

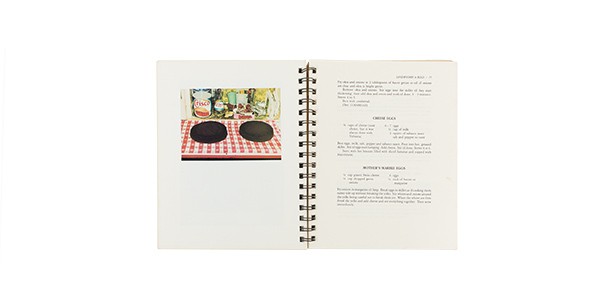

Ernest Matthew Mickler ⋅ White Trash Cooking

The Jargon Society and Ten Speed Press ⋅ Berkeley, CA, 1986

White Trash Cooking (The Jargon Society and Ten Speed Press, 1986), by contrast, is the antithesis of the Time Life Picture Cookbook, a spoof, but one with a great deal of love at its heart. (The Jargon Society, founded by the late North Carolinian poet and Black Mountain College alum Jonathan Williams, was better known for publishing avant-garde books of poetry and photography.) The book is a satirical counterpoint to the more serious cookbooks of the day that had begun fetishizing freshness and local ingredients with the rise of Chez Panisse. The recipes, like Tutti’s Fancy Fruited Porkettes, Mock-Cooter Stew, Oven-Baked Possum, and Four-Can Deep Tuna Pie, are written in a down-home voice. But through the tongue-in-cheek, it is clear there is genuine affection for the people and respect for the country dishes. Nothing reflects this more than the surprise center section of color photographs, taken by the author, Ernest Matthew Mickler, on his travels through the South as he collected the recipes. There is no irony here. The pictures are casual, direct, and elegiac. They reference FSA pictures from the region and resemble William Christenberry’s pictures of Alabama with their sense that this way of life is becoming a memory. Bushels of peaches, old stoves, rusty bedframes in the landscape, people on porches, cornpones on the stove show a different kind of local lifestyle. Though the pictures would still work in a traditional photobook context, in the cookbook they operate to both cut the edge of the White Trash Cooking’s joke, and to deepen the satire against other lifestyle cookbooks, by revealing something much more sincere. In the last picture, the two devil’s food cakes cooling on the counter look like black portals into another time. That Mickler could convey such depth in front of a tub of Crisco is remarkable. Publishers first rejected the book and the New Yorker refused to run an ad for it, but it became an instant classic.

Ernest Matthew Mickler ⋅ White Trash Cooking

The Jargon Society and Ten Speed Press ⋅ Berkeley, CA, 1986

Today if you walk through the cookbook section of any store, you will notice that the books there look a lot like art books. This trend may have started out of necessity; with the rise of digital books, printed books needed to justify their existence and amplify their shelf appeal to entice consumers. To achieve that, publishers have reached into the bag of tricks established in art and design books, including photobooks. An early adopter of this recent trend is Breakfast Lunch Tea (Phaidon, 2006). This was the first cookbook wholly originated by Phaidon, after its success with Silver Spoon (a buy-in with Editoriale Domus for the 1950 Italian classic Il Cucchiaio d’argento). It is no surprise that this book takes the form of an artbook since this is what Phaidon knows best. Toby Glanville, a wonderful British portraitist, took the photographs and presents an utterly lovely portrait of a bakery: those who work there, the regulars, the purveyors, the ingredients, the process, and the finished food. Glanville’s unusual color palette, striking angles, and unassuming portraits make for a beautiful book. This, combined with the high quality paper and printing, elevate the cookbook into more of a photobook. Phaidon continued this type of treatment in their future cookbooks, and many other publishers have followed in their wake.

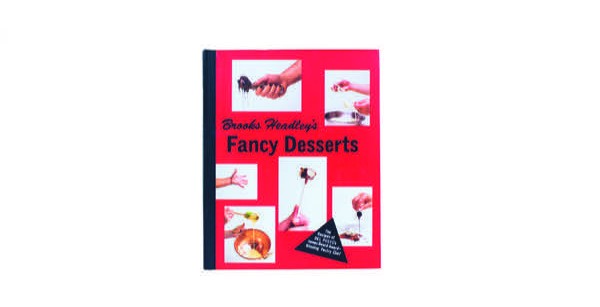

Brooks Headley ⋅ Brooks Headley’s Fancy Desserts: The Recipes of Del Posto’s James Beard Award-Winning Pastry Chef

W. W. Norton ⋅ New York, 2014

Perhaps in reaction to this movement, Brooks Headley’s Fancy Desserts (W. W. Norton & Company, 2014) is a serious cookbook, but also pokes fun at today’s delicate pastry cookbooks with their restrained color palettes and selective focus. Instead, the Fancy Desserts pictures, a collaboration between photographer Jason Fulford and illustrator and author Tamara Shopsin, are playful, each with their own deadpan joke, and shot almost entirely against a plain white background. The red cover says it all with sticky hands, sauce poured out from proportionally tiny creamer, dripping chocolate from poorly painted fingernails, and a rather unappetizing mystery dough (cheese, actually). The book feels more punk than lighthearted with clever inside references and, at times, a gross-out take on pastry, more akin to a food fight than a white table experience. We rarely see the fragile and fancy final dishes, just the crazy process, complete with a condensed milk bomb. The book is purposefully not tasteful, deflating the very notion of fancy, and subverting the increasingly precious cookbooks-as-artbook genre. The fact that the book accomplishes this with art stars Jason Fulford and Tamara Shopsin at the design helm is a large part of its genius. Sadly, the publisher just released a paperback edition replacing the original cover with a more expected picture of fancy dessert. Chickens!

Denise Wolff is a senior editor at Aperture. Some recent books she has commissioned include The Photographer’s Cookbook (2016); The Photography Workshop Series books; and Seeing Things (2016), a children’s book by Joel Meyerowitz.