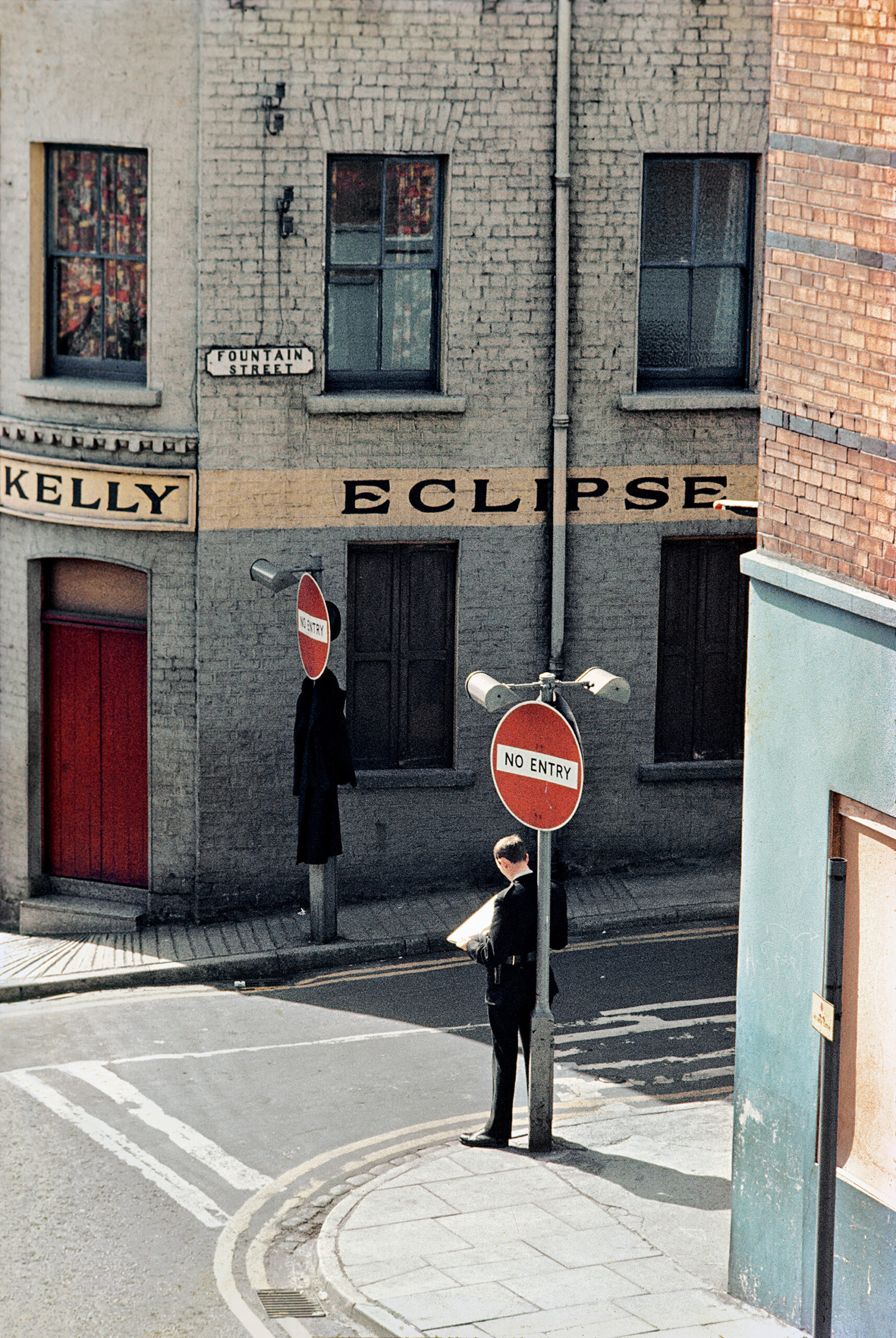

Akihiko Okamura, The Fountain area, Derry city, Northern Ireland, ca. 1969

Early in the BBC documentary series Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland (2023), a powerful collection of personal testimonies on the Troubles, one speaker recalls his childhood excitement during the first waves of civil unrest. “It was mad . . . it was like a movie,” he reminisces, thinking back on the innocent elation he experienced as mass protests, running street battles, and military patrols became regular features of everyday life. Inevitably, as the daily drama intensified, with bombings, shootings, and funerals dominating the headlines, the desperate gravity of the situation became clear. Even to kids playing with pretend guns on the backstreets of Derry and Belfast, as the BBC interviewee remembers, “this was serious . . . it wasn’t like a movie anymore.”

The Japanese photographer Akihiko Okamura first visited Northern Ireland during this formative phase of the thirty-year conflict, and his images capture, with understated eloquence, a sense of reality as shifting and unstable, both not quite real and all too real. In 1968, Okamura moved to Dublin with his family, prompted by a plan to explore the Irish roots of President John F. Kennedy. From there he made numerous trips north of the border, documenting occasions of historic significance, such as landmark civil rights marches, while also attending to people and places on the margins of the era’s main events.

Okamura was unfamiliar with the specific circumstances of Northern Ireland’s political divisions but no stranger to societies upturned by warfare, struggle, and suffering. Before settling in Ireland, he had photographed the chaos and cruelty of the Vietnam War, gaining extraordinary access to Viet Cong camps, and traveled to Cambodia, Malaysia, and Korea, documenting life in nations coping with the corrosive, long-term effects of colonialism. (Later, he also reported on the Nigerian Civil War and journeyed through Ethiopia, photographing victims of famine.) Tracking political developments and, more routinely, everyday existence in Ireland during the late 1960s and early ’70s, Okamura brought a worldly outsider’s capacity to find surprising new angles and the patience and sensitivity of someone willing to stick around, to look beyond the breaking news.

Okamura singles out low-key moments, discovering worlds within worlds.

The pictures selected for Atelier EXB’s publication Akihiko Okamura: Les Souvenirs des autres (The Memories of Others, 2024) and an associated exhibition at the Photo Museum Ireland, Dublin, showcase Okamura’s subtly modulating stylistic range, combining moments of big-picture photojournalistic storytelling, gently surrealistic black comedy, and hazily dreamlike glimpses of communities or individuals in states of fearful transition or uneasy stasis. Some images have orthodox historical value. There are, for instance, valuable shots of key characters in early episodes of the Troubles. Okamura catches the stern vanity of the firebrand sectarian preacher Ian Paisley as he lays a wreath at the culmination of an Ulster Loyalist parade, his hair slicked and quiffed like a ’50s rock-and-roll star. The civil rights activist Bernadette Devlin, Paisley’s left-wing, nonsectarian rival for the most dynamic public speaker of the era, is memorably pictured in a typical pose: megaphone in hand, leading the action from a barricade during Derry’s Battle of the Bogside in 1969. The most resonant of the photographs, however, are those with more unassuming, antiheroic attributes. They stir feelings of unusual intimacy with characters living through the strange convulsions of their times.

Okamura singles out low-key moments, discovering worlds within worlds. He seems to be, as W. G. Sebald once said of his fellow writer Robert Walser, a “clairvoyant of the small,” looking for what we might learn of desire, sadness, loneliness, or dreaming among the dispersed, matter-of-fact materials of daily life. Two women clamber through a makeshift army barricade; one wears a bright red coat, its cheerful design an incidental affront to the surrounding gloom. Two little girls, prim and dainty in their Sunday best, pay their respects at an improvised memorial to a shooting victim on a Derry street. Behind the shadowy presence of an armed soldier in heavy fatigues, a pair of pristine white wedding dresses appear in the window of a bridal shop. Another lone figure, a young man in a slim-fitting suit, leans against a lamppost reading a newspaper; above him, street and shop signs declare “No Entry” and “Eclipse.”

All photographs © Estate of Akihiko Okamura/Junko Sato

There are quite a few signs in Okamura’s Irish oeuvre: street names, traffic directions, advertising posters. Here and there, the texts hint at hope of stable meaning—such as in one picture of a grieving woman carrying a protest banner, appealing for justice—or unbending allegiance to a political position: in another shot, showing residents gaily decorating a terraced street for the Unionist community’s Twelfth of July celebrations, we see the intransigent slogan “No Surrender” emblazoned on a wall mural. Often, words produce moments of mischievous irony: a helmeted soldier, bearing a shield and a baton, framed partially by a sign saying “caterers”; or the words “Police Enquiries” posted outside a fortified Royal Ulster Constabulary station, barely visible on the ludicrously forbidding sheet metal facade. If with such teasing image-text contradictions Okamura gestured toward satire, he did so without becoming direct or dogmatic. However dark their humor, however bleak their mood, his photographs create space to see ordinary life at the time of the Troubles a little differently: one unexpected scene, one small detail, after another.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue,” under the column Viewfinder.

Akihiko Okamura: The Memories of Others is on view at the Photo Museum Ireland through July 6, 2024.