Picturing the American Family, from Frederick Douglass to Jamel Shabazz

In this conversation, Rhea L. Combs and Deborah Willis speak to the power of photographs to envision love and connection for Black American families.

“I have found no standard art history that refers to any Afro-American artist,” Deborah Willis wrote on November 14, 1973, in a statement about her intention to research the contributions of black photographers from 1840 to 1940. After approaching a number of collections and libraries, and drawing up a list that included Roy DeCarava, James VanDerZee, and Gordon Parks, she asked herself: “Could these black photographers receive the same recognition their white colleagues received?” This question has animated Willis’s groundbreaking books, essays, conferences, and curatorial projects concerning the relationship between African American identity and photography, and brought to the foreground the stories of black people as both makers and subjects of images, from Civil War-era portraits to contemporary photo-based art.

For Willis, a distinguished professor of photography at New York University, the image of the family has been central, and deeply personal. Two years after the opening of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., where the story of the American family is told and presented through images, Willis spoke with curator Rhea L. Combs about the enduring legacy—and political resonance—of the African American family in photographs.

Courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Rhea L. Combs: For decades, you’ve been involved with and dedicated to the life and work of African American image makers. You’ve done groundbreaking research and helped shape and mold some of the brightest minds and thinkers in the field, past and present. What motivated you to do this work, and why photography in particular?

Deborah Willis: I grew up with a father who was the family photographer. As an amateur, he had a Rolleiflex. We had a lot of family events, reunions, and gatherings up until my first year in college, and my dad took most of the photographs. He had a cousin, Alphonso Willis, who had a studio about two or three blocks away from our home, and he took the official portraits with his big 4-by-5-inch camera. Our neighbor was Jack Franklin, who was a photojournalist for the black press in Philadelphia. I also grew up in a beauty shop, as you know, and having that opportunity to look at magazines most of my life, from Ebony to Life, meant that I was always looking at photographs.

Combs: Was there any distinction between what you saw in Ebony and Life and what you were experiencing in the family photographs that your father was taking?

Willis: I always thought that our family stories weren’t visible in the larger magazines, like Life and Look. Ebony definitely had images of black families, but mostly black celebrity families, as well as people who were successful in business or in politics. When I was younger and heading to college, I wanted to make visible some of the stories of the everyday experiences that I enjoyed watching in my neighborhood and within my family, like kids playing jump rope, people seated at a table. And what I found was The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), the book by Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes. It excited me, even as a younger child, seeing that book. Having family images in the living room, on the mantle, on walls—family photographs were our art form.

© Yoors Family Partnership and courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs, New York, and Gallery Fifty One, Antwerp

Combs: Same for me. Those were the visual cues that let you know you were home.

Willis: Absolutely.

Combs: A lot of your research projects and books expose people to the work of early African American photographers. Once you uncovered these jewels and these photographers, how did they influence your work or help you unpack these ideas around family?

Willis: My family were members of the NAACP, so they had a subscription to its magazine, The Crisis. Growing up with The Crisis in the house and then going to school and learning about W. E. B. Du Bois and his impact on photography was a nice kind of collaboration in my memory. When I started to think about studying photography and the history of photography, I noticed that there were no black photographers in the history books. Even in the 1970s, Gordon Parks was not in my history of photography book, and I had read his book A Choice of Weapons (1966) by then. So I thought, Okay, we need to make a change in this. A professor encouraged me to do a paper on the topic. As a result, I started going through the black press, looking at black newspapers and ads, and finding city directories that had black photographers. I wanted to start at the beginning of photography, because I believed that they were there, that they existed. I knew it. I was lucky enough to find early photographers who were working in the 1840s and 1850s, free men who were also activists and abolitionists. So that was the beginning of a research paper as an undergraduate, when I was looking to fill in the gap in my classroom. That’s how that happened.

Then what I found was that black photographers were photographing black families. At that time, there were a number of stereotyped—troublesome, to me, visually—images of black people in stereographs that circulated in the public, while, at the same time, in the black communities, there were images of successful, proud, happy—not grinning, but happy—black people, happy to be alive, living through a difficult time.

Courtesy the artist

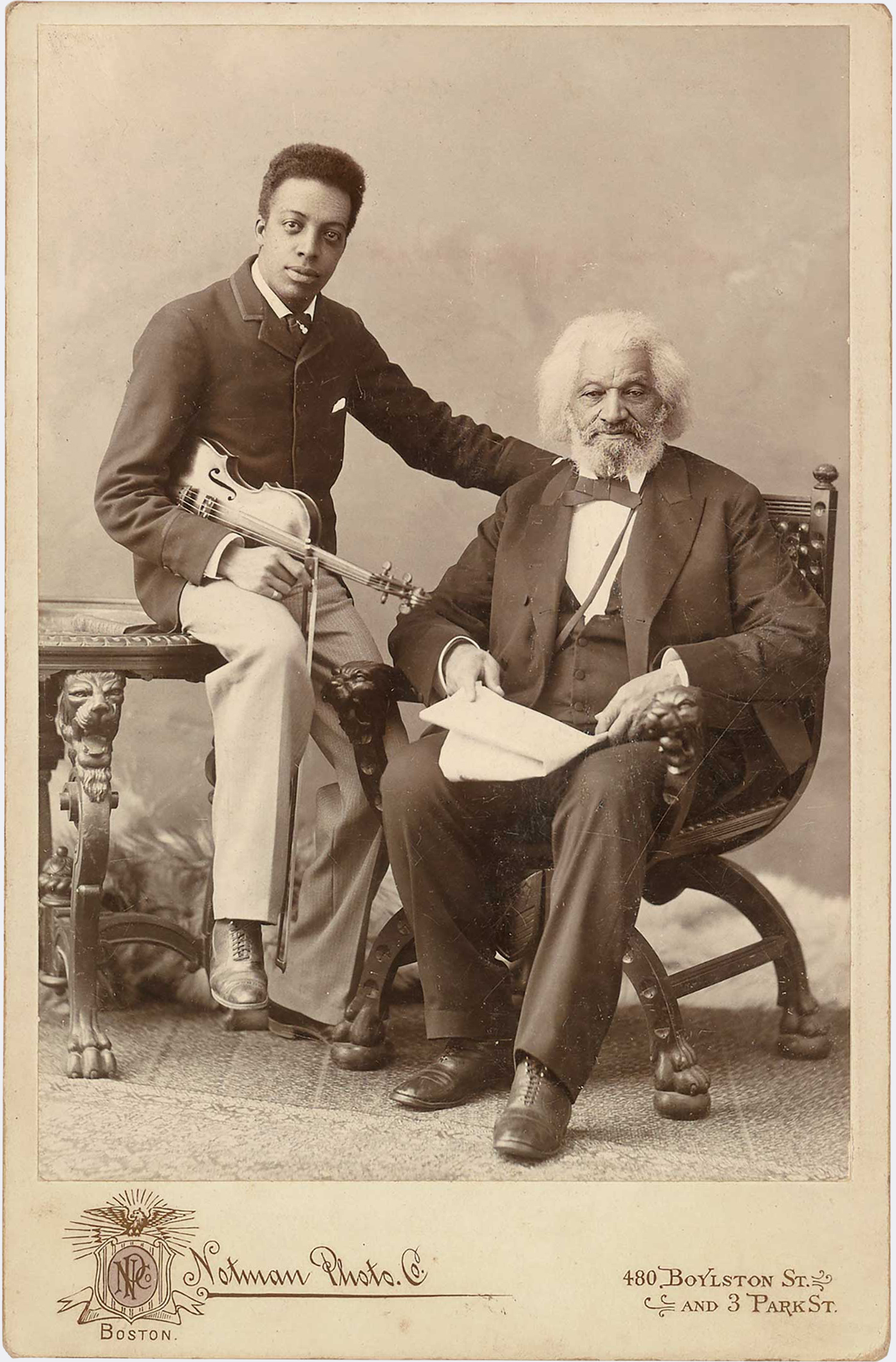

Combs: When you think about photographs of Eva and Alida Stewart, Harriet Tubman’s great-nieces, or the carte de visite of Frederick Douglass and his grandson Joseph Douglass, or photographs of Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, how do you situate these images within the context of your research?

Willis: In the image of Harriet Tubman’s great-nieces—we are familiar with women and adornment, in terms of hats and how they’re seen, and so we are reminded of a past that has been neglected, that has not been discussed in family photography. Women were dressmakers. They created patterns and styles. They looked at magazines. Black women were known as great milliners during this time of the 1890s and early 1900s. In the picture of Tubman’s great-nieces, we can see these prosperous, educated, happy women photographed together, and they’re wearing jewelry, and one has her head cocked to the side, and the other one is looking directly into the camera. Both were sending the message of success and strength—similar to the women in Jan Yoors’s photograph of a wedding in Harlem in the 1960s. The way that they’re wearing their hats—we can connect the fashion of women of that time to the fashion of the women in the 1890s.

I remember seeing the image of Frederick Douglass with his grandson when I was first working at the Schomburg Center, in New York. We know Douglass fought for his family, like the Civil War soldiers fought for their families. In this image, we see him with his grandson, who was a musician, and we see the story. But also, we know it’s in a fancy studio; we can see the furniture in the back. Douglass was using these studios to create a narrative about black life and black experiences.

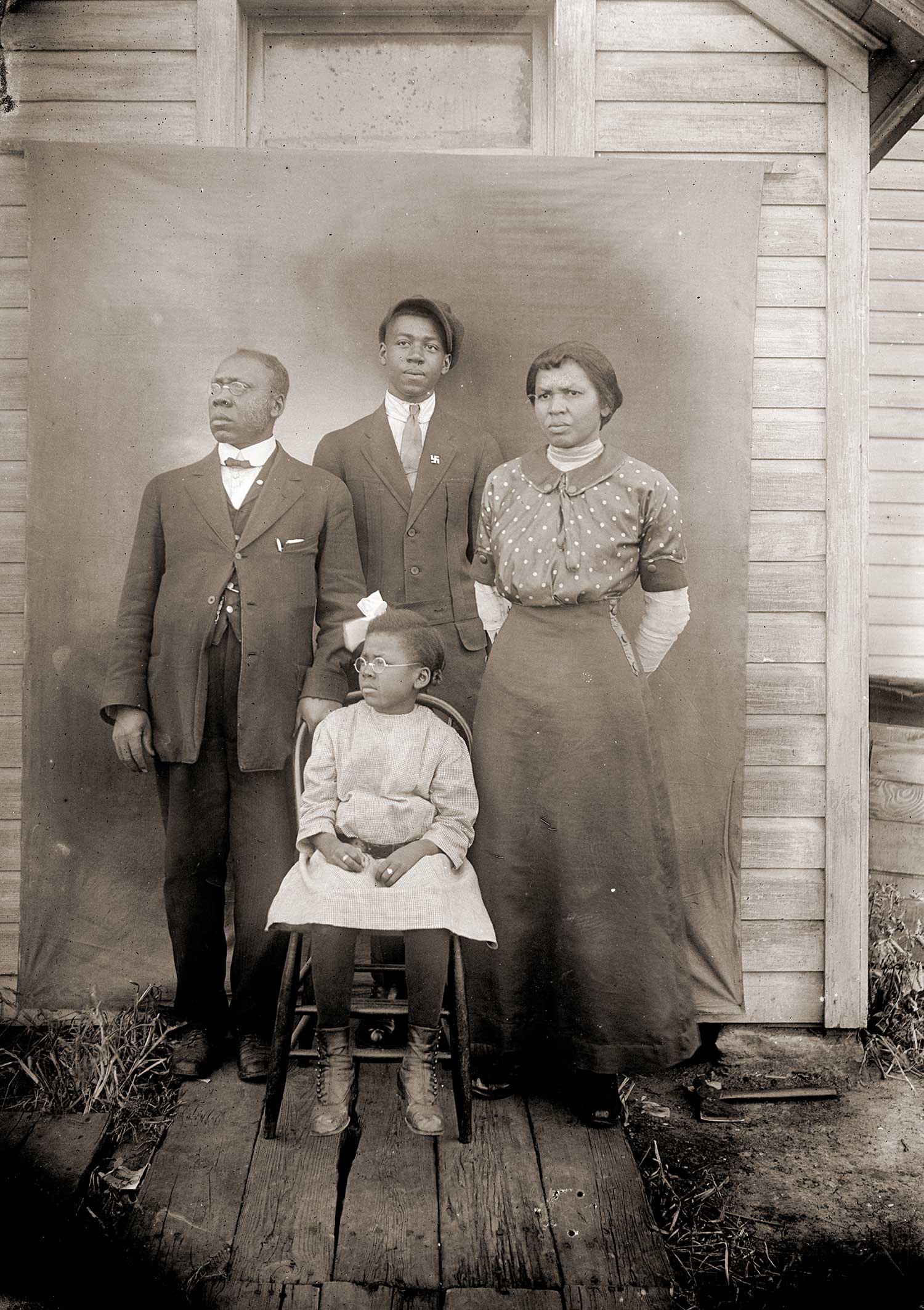

Courtesy the Douglas Keister Collection

Combs: To your point of Frederick Douglass and Joseph Douglass—you see them, as you stated, in this established studio, and there is a sense of prominence. You could juxtapose that with the print of the Talbert family standing in front of a photographic backdrop not in a studio, but outdoors, made around 1914 by the photographer John Johnson. But there’s still a sense of regality and pride and esteem that is established by this family.

Willis: Right. And it’s known to be of Reverend Albert W. Talbert and his family. So we know his station in the community. It’s probably a rural community, and we see that it was important for his family to be photographed, probably for an official church portrait.

Combs: This was in Nebraska.

Willis: One button closed. This is probably not the original one that Johnson, the photographer, selected. We see the scene beyond the backdrop—we see where the photographer could actually crop the image to just show the family as if they were standing in a lighted photographic studio. And the way Reverend Talbert’s son wears his hat—the way that he cuffs the brim—looks as if he is a bit rebellious. He’s wearing the style of the time of the young sporty man.

Combs: Totally.

Willis: The good daughter, with her bow, and the rebellious son, and the supportive wife. Isn’t it wonderful to see the complexity of families, and the stories that are told through photographs?

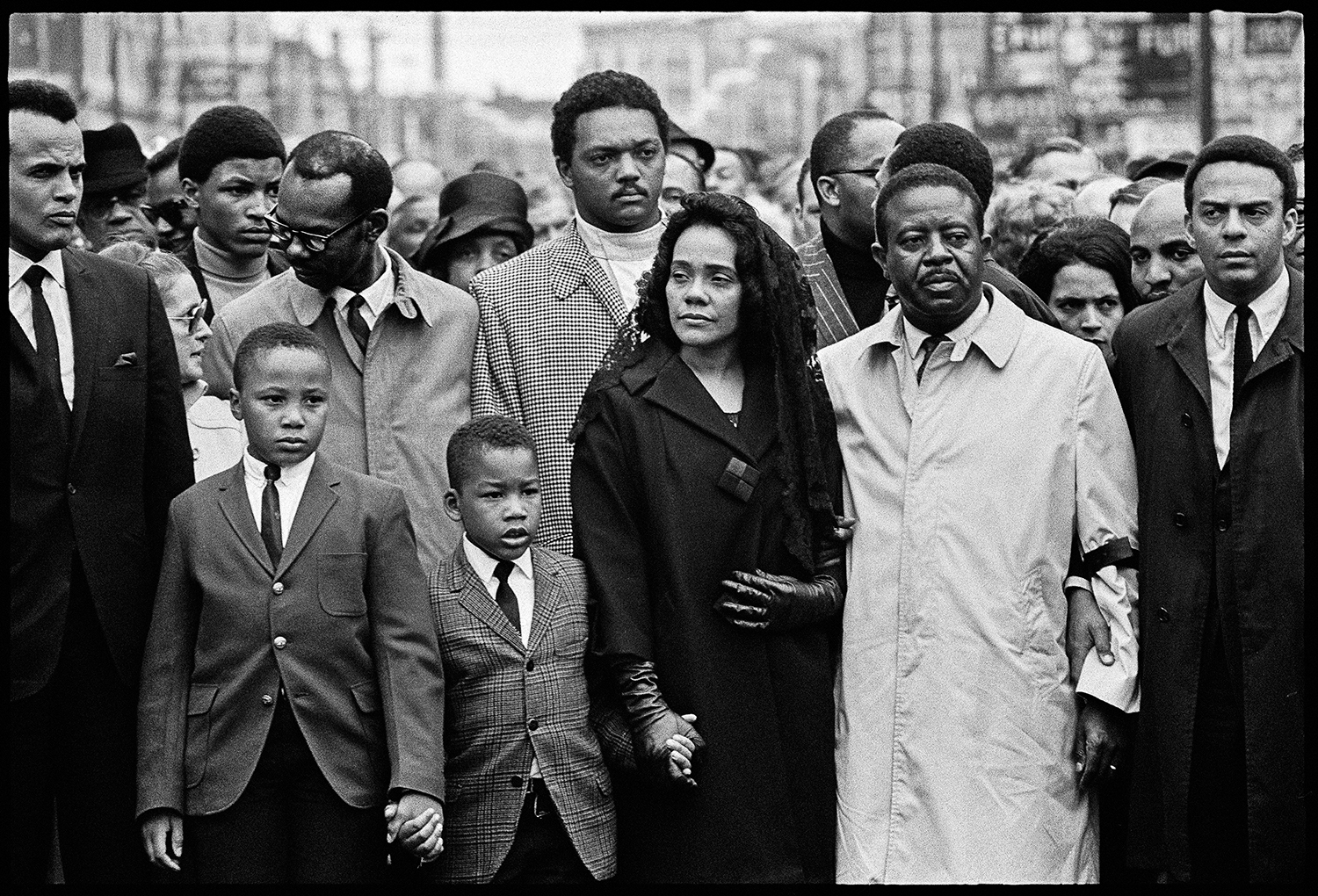

We see in an early 1950s image of Emmett Till and his mother the pride that his mother had in posing with her son. She is looking away from the camera; he is looking directly into it. He is happy to be with his mother, happy to be photographed. Think about this along with the image of Martin Luther King Jr.’s family at his funeral: here are two images of people who’ve lost family members in a violent manner. We see two mothers with sons. The sense of protection, the sense of having them as witnesses within that frame.

Courtesy the artist

Combs: How do you think family photographs have been utilized as a way of understanding the civil rights movement?

Willis: Black photographers like Gordon Parks, Ernest Withers, and Moneta Sleet took their cameras into these communities to look at injustice and asked: How do we educate our children? How do we think about the future of our children? Photographs helped to push the spirit of black people during that time, to think about the act of being photographed as a representative family member, to walk to church, to walk to school, to go to vote, to be activists.

Combs: What you said brings us to the work of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is committed to telling the story of America primarily through the African American lens. In many ways, its physical place becomes a space where families can gather, either literally or metaphorically, through images. I would love to hear from you how this notion of family and family photography, even photo albums, can help tell the American story.

Willis: I think about the images that we know from the movement, and about families who used the Green Book to travel safely, to know where they could rest, stop, and get food. They didn’t have social media then; they had word-of-mouth. And that’s how most families survived during migration and on vacation—it was because one sent a postcard photograph of a family member. The photographs in the museum are essential for showing a contemporary viewer that path. That’s why Du Bois, in the photographs he selected for the Exhibit of American Negroes at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, included Thomas Askew’s photographs taken at homes: they show ownership by blacks. This is right after emancipation, and this was the hope of emancipation—that people could buy homes and perform the duties of family, church, and civic life.

Combs: There’s also an interplay between intimate moments and vernacular photography and interior spaces. I love one particular photograph in the museum’s collection of a young woman with go-go shorts and little heels, posing in the living room. And also another vernacular photograph that was found by photographer and collector, Adreinne Waheed, of this interior space of a family gathering down in, I’d imagine, a basement.

Willis: It reminds me of my house in North Philadelphia. They played cards. They sang and listened to music. They loved dancing. And all this is a memory that’s part of my memory of pure pleasure. Not just family members, but their family friends.

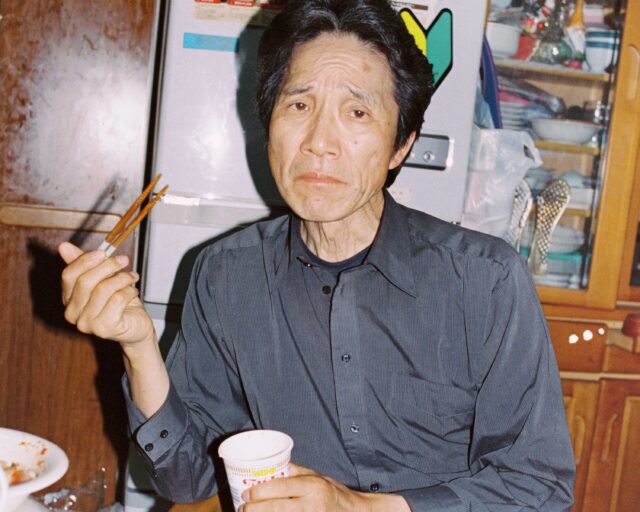

Courtesy the artist

Combs: How do you think an image is affected by who is taking the photograph? Especially as it relates to family photographs.

Willis: Jamel Shabazz is a person who loves photographing groups and people. You can see it in the way he uses that love as a sense of getting to know people through photographing them. Zun Lee’s collection of Polaroids is a way to think about textural memory and visual memory. The first car. The red shoes. Going to church on Easter Sunday. Going to a wedding. Just documenting the sense of joy. We can see what it meant for a black man to buy his child a gift and to pose for it.

Combs: What are the differences between Lee’s image of a man sitting on a toy car with his children and Frederick Douglass posing with his grandson? How do you see the arc shifting across the formal nineteenth-century photographs to the Polaroid photographs, which are so accessible?

Willis: I imagine that the impact is the same. They wanted to document and celebrate a moment and a memory. It’s part of that reflection on why photography of families is so important.

Courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Combs: I also wonder what we are not seeing in these photographs. I recognize that families are complex and dynamic, and relationships can run the gamut. So when you see the range of images, intergenerational connections, and the role of family, is there a way in which you could surmise what issues these photographs are not engaging with?

Willis: Well, we think about divorce in families. Family photographs are remembered in certain ways. We think about abuse; who is the abuser in the photograph? When we think about what’s missing in family photographs, we often say that the queer or the trans family members are often not photographed. But sometimes you see that sense of love in those photographs, too. We know that a person is presented a certain way in the photograph. How do we tell that story about a queer family member or a trans family member, and the acceptance of that?

Combs: I was thinking about your recent TED Talk with your son, Hank Willis Thomas, and about how photography is instrumental to your work and his. You articulated so beautifully about love as a verb, and how that infuses and is incorporated in your art. When you think about your body of work and how family has been so critical to your research, I wonder if there’s a way in which your philosophy around love and family and photography filters into the things we’ve discussed.

Willis: The love that I find represented in family photographs—even if there’s abuse and there’s separation—is the initial part that is historicized, the love of family. I just had a death in the family, and we had to collect photographs. My aunt, who was eighty-eight, was a stylishly dressed woman for as long as I remember. All of her photographs show her sense of style, and her love of the camera and of people. We celebrate death with photographs, just as we celebrate life.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 233, “Family.”