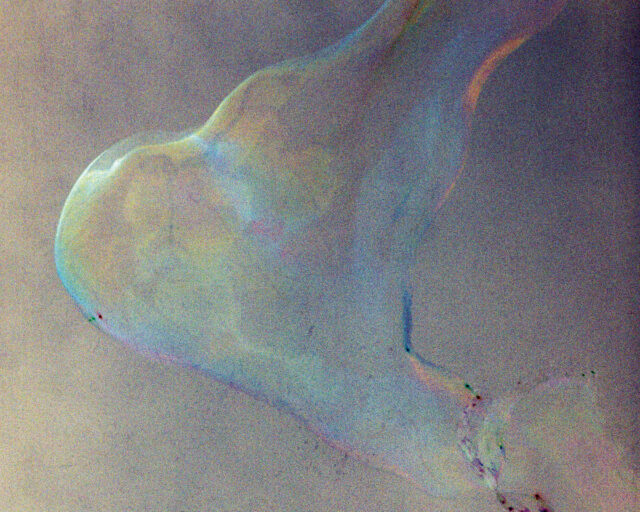

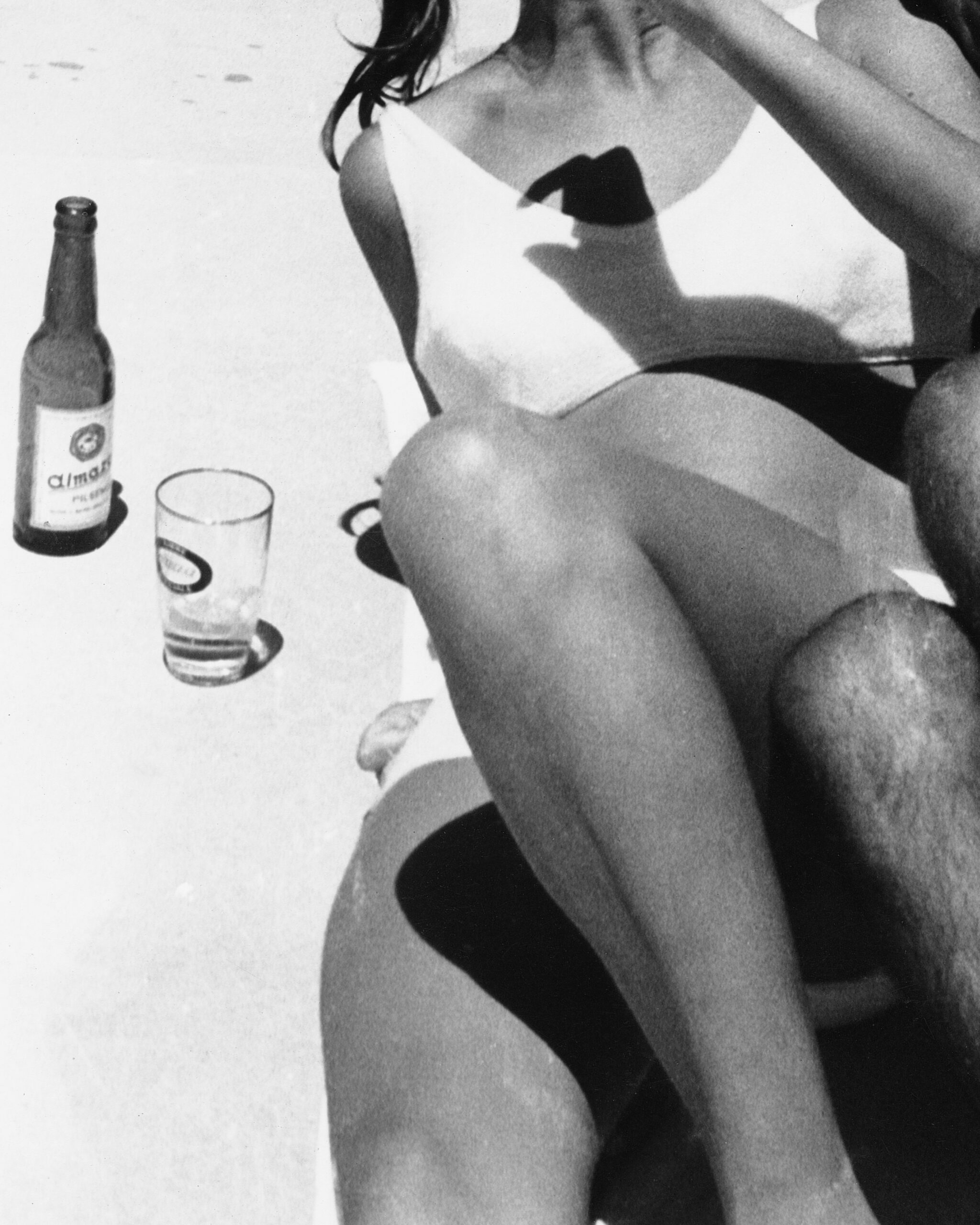

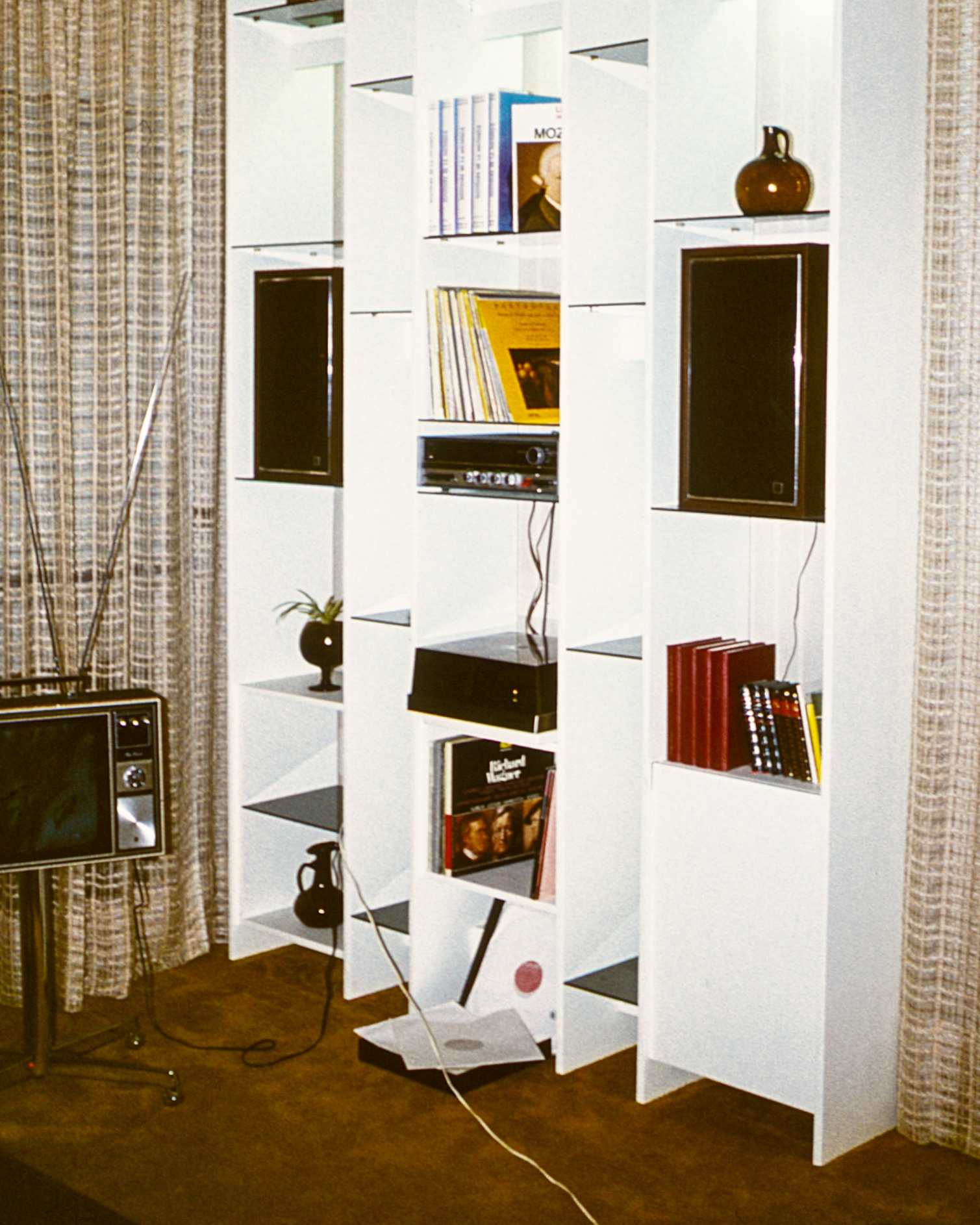

Tanya Traboulsi, from the series Beirut, Recurring Dream, 2021–ongoing

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Winter 2023, “Desire,” under the column Dispatches.

Tanya Traboulsi is an ardent observer of the Lebanese coastline. Her photographs probe the ways in which clay tennis courts and fake grass playing fields are tucked into the hills sliding down to the sea in Ras Beirut, on the western side of the city’s promontory. She is also a dedicated student of vernacular architecture. She details vestibules, awnings, bougainvillea peeking through tactical breeze-blocks, and the elegant arches of a derelict Ottoman mansion. She returns again and again to the playfulness with which shopkeepers in the Lebanese capital use language to advertise the Renaissance Sporting Club, New Fashion, or Dalida, a tiny chocolatier downgraded under financial duress to an all-purpose dekaneh, or grocery store, named for a pop music sensation.

Traboulsi’s series Beirut, Recurring Dream (2021–ongoing) pairs photographs she has taken in the last two years with images from her personal archive: six large boxes of material, including family albums and pictures she took during her childhood and adolescence. Traboulsi’s diptychs are fluid and unfixed. They appear in different configurations, depending on their context. They are also matched by intuition. By placing a photograph of a couple lounging on a beach in the 1960s next to an image of a woman standing alone, her back to the viewer, on the corner of a low wall jutting into the sea, as she gazes toward a blurry horizon and ambivalent skies, Traboulsi isn’t suggesting narrative so much as time travel or a flash of inherited memory.

Traboulsi was seven years old when she left Beirut with her family on a boat crossing the Mediterranean Sea. It was 1983. Lebanon’s civil war was lurching through its first decade. The center of the capital had been destroyed in the first round of fighting, starting in 1975. Beirut was split in half and the armed forces had fractured. The government was about to collapse. Massacres had occurred all over the country, and there was shelling in densely residential neighborhoods. Syria had intervened, and in 1982, Israel had invaded and besieged the country, which, among other things, closed the airport for months at a time. Fleeing residents had to risk dangerous mountain roads or the ferry lines connecting Beirut to Cyprus.

As a city, Beirut has been photographed with a prodigiousness disproportionate to its size, even its history.

Traboulsi’s parents met before the civil war began. Her mother had moved to Lebanon from Vienna to work as a ski instructor, and Traboulsi’s father cut the line to sit with her on the lift. An enduring romance ensued. Traboulsi was born in Austria but spent her early years in Beirut, taking pictures of the city using an Instamatic camera and 110 film. Her family left and stayed away for more than a decade, in part because the civil war lasted so long and in part because it ended with such uncertainty. A general amnesty was announced in 1991, although some argue the conflict continued by other means.

“The moment I left, I wanted to go back,” Traboulsi told me this past summer. “The image of how Beirut looked from the sea stuck with me for thirteen years.” She was separated from her two best friends in Lebanon and saw them constantly in her dreams. She didn’t return until 1996. From that point, she shuttled back and forth between Austria and Lebanon until she finished university. She settled in Beirut in 2003.

As a city, Beirut has been photographed with a prodigiousness disproportionate to its size, even its history. The so-called photographic mission of 1991 invited six leading photographers—Gabriele Basilico, Raymond Depardon, Fouad Elkoury, René Burri, Josef Koudelka, and Robert Frank—to document the tremendous violence done to the heart of Beirut’s city center by fifteen years of civil war. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, artists and filmmakers such as Walid Raad, Jalal Toufic, and Akram Zaatari responded to the conditions of postwar and reconstruction-era Beirut with their own trenchant questions. In their wake, Traboulsi has emerged as one of the city’s most thoughtful and affectionate chroniclers.

Traboulsi and I are nearly the same age and came to live in Beirut at the same time. In many ways, her photographs narrate my own relationship to the city. She has photographed buildings I have lived in, corners I have loved, places I have walked by and wondered about daily. I vividly remember my first encounter with her work, in a group show called Be-Sides: How Young Lebanese Photographers See Present-Day Lebanon, organized by the Goethe-Institut in 2007.

Beirut’s photographic history can make the city feel trapped in the past, forever in the rubble of the civil war. But Traboulsi has stayed with the story and followed the city through more recent upheavals. With great subtlety and sensitivity, in Beirut, Recurring Dream she gathers traces of the revolution that erupted in 2019, followed by the economic collapse that devalued the local currency by 90 percent and plunged more than half the country into poverty. She captures the afterlives of the catastrophic explosion that ripped through the port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, killing hundreds, injuring thousands, and displacing three hundred thousand people from their damaged homes.

Courtesy the artist

“The explosion changed everything,” Traboulsi told me. “It changed me, my friendships, my relationships, my view of love, what I accept and what I can give to other people.” Seeing the city so damaged compelled her to admit that Beirut was and always had been her subject.

The Lebanese poet Etel Adnan described a mountain in California as her best friend. She painted it every day, in all kinds of light and weather, for more than a year. This was in the mid-1980s, after Adnan, the ultimate chronicler of Beirut, had made her own exit from the city and Lebanon’s civil war. In 2021, Traboulsi made a film with the writer Ibrahim Nehme, unrelated to Beirut, Recurring Dream, called Son of the Sun. Nehme’s voiceover offers a visceral response to the port explosion (he was seriously injured in the blast), but Traboulsi’s images are long, steady shots of the sun rising and falling on the coastline, waves lapping the shore. Adnan had her mountain, Traboulsi has her city on the sea.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Winter 2023, “Desire.”