Aperture #211—What Matters Now?

Photographs as Things

Photographs, especially personal ones, have always served as physical manifestations of memory. Held between fingers or hung on a wall, photographic prints had a direct material connection to their subjects, from light to lens to film to paper. Today, of course, our photographs are born digital. Their power as images remains, gloriously so; but their reality as objects is often lost.

In my house, these two ideas collide in the small hands of my three-year-old daughter, compulsively snapping photographs with a phone snatched off the table. She has amassed hundreds of them (mostly of fingers and floors). They are not merely weightless, but evanescent. So in an effort to fix them in the most literal way, we bought a sixty-nine-dollar wireless printer. The effect was strange: a photograph taken with one magic box was magically transferred through the air to another magic box, out of which a photograph (on paper!) slowly emerged. Up it went on the refrigerator door. The images themselves are beside the point. What I am grasping for, perhaps foolishly, is the sense of a photograph as a thing, an object of value—something to be cared for in the physical world, as we care for each other.

—Andrew Blum, journalist and author of Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet (Ecco, 2012)

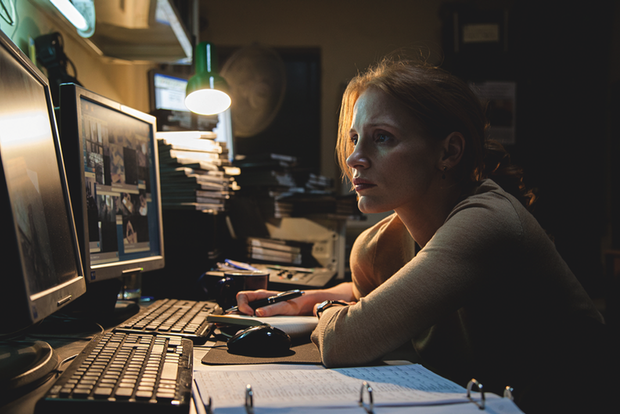

CIA Torture Tapes

Production still from the film Zero Dark Thirty, 2012 (dir. Kathryn Bigelow). Photograph by Jonathan Olley. © Zero Dark Thirty, LLC. All rights reserved.

For the past several years I have been obsessed with images I’ve never seen. They were recorded and destroyed. These images document torture. In their absence, fictitious images have emerged.

Jose Rodriguez, the man who in 2005 ordered the destruction of ninety-two videotapes of torture committed by the Central Intelligence Agency, claims: “I was not depriving anyone of information about what was done or what was said. I was just getting rid of some ugly visuals that could put the lives of my people at risk.”

Rodriguez, a high-ranking intelligence officer, made the decision to destroy the torture tapes in response to the public reaction to the Abu Ghraib photographs in 2004. It is often forgotten that the abuse at Abu Ghraib was made “public” before those images were released. Four months before the publication of the photographs, the U.S. military issued a press release saying they were investigating claims of prisoner abuse in Iraq. The announcement received little media coverage or interest. Had the photographs not been leaked to the New Yorker and 60 Minutes, Abu Ghraib would likely have disappeared from history.

Without visual evidence of CIA torture, history is being written by Hollywood. In Zero Dark Thirty, the CIA torturers are the heroic protagonists. Can we imagine this happening with Lynndie England, the woman holding the end of a dog leash around the neck of a naked prisoner at Abu Ghraib? Or Sabrina Harman, who gives the “thumbs up” sign over the dead body of Manadel al-Jamadi, a man killed during a CIA interrogation?

If the CIA’s torture tapes had been made public, how would history be told differently?

—Laura Poitras, documentary filmmaker and MacArthur Fellow, whose work includes The Oath (2010); My Country, My Country (2006); The Program (New York Times Op-Doc, 2012); and Death of a Prisoner (New York Times Op-Doc, 2013)

North Korea’s Gulag

After Hurricane Sandy last year, photographer Iwan Baan captured an iconic shot of Manhattan, half in blackout: it is a photograph that will haunt our collective memory for a long time. At the same time, Google Maps recently added North Korean coverage by means of a clever juxtaposition of aerial shots, satellite imagery, and clandestine on-the-ground documentary photos by daring locals and visitors alike, giving us firsthand views of this notoriously media-shy country and its equally notorious death camps. With this ostensibly minor extension of its mapping service, everyone’s favorite search engine entered the political arena—and Google deserves great credit for this unexpected advance. In the end, this “citizen documentation” of actual gulags on North Korean ground is more likely to unsettle the restrictive regime than any international sanctions.

Both Baan’s image and Google Maps in North Korea have reignited my appreciation for straightforward reportage that channels and politicizes key issues via powerful visual records. When I think about Vietnam, the Cold War, or space-age advances—as well as events that occurred before my lifetime—I consider those times and events through iconic press shots that strike a mental, emotional, and sociopolitical chord. Images help us to contextualize topics, ideas, and historical events. Great press photographs trigger desires, anger, compassion: they get me going. I expect photography to play a powerful part in developing my political agenda. I believe that the decline of quality news outlets goes hand in hand with a decline in empathy, political involvement, and democratic engagement. We are ready for a new breed of earnest and enthusiastic photojournalists who can produce those shots that capture our hearts and minds.

—Robert Klanten, founder and publisher of Gestalten, Berlin

Possibilities of Pleasure

A favorite image from the past few years is by Maha Maamoun. What is depicted is a children’s playground in a Cairo park, dominated by an aging tubular metal slide, which is painted in the bright colors of the flag of the Arab Republic of Egypt and bears an inscription in Arabic that translates to: “Baby Land Welcomes You!” Two small girls and a toddler boy are about to climb the stairs to the top of the slide, while a young woman in gray veil is helping another woman, in a black niqab, who just slid down, to emerge from the industrial-looking orifice at the bottom of the slide.

The image, which is humorous, sad, and indicative of a certain psychosis, brings to my mind a 1920 drawing by Max Ernst called The Hat Makes the Man, which is full of colorful tubular forms and men’s black hats, and bears a cryptic inscription: “seedcovered stacked-up man seedless waterformer [edelformer] well fitting nervous system also tightly fitting nerves! (the hat makes the man) (style is the tailor).” Like Ernst’s drawing—which suggests a kind of an alchemical-industrial transubstantiation of masculinity— Maamoun’s photograph delicately charts a cosmology of women’s lives and the possibilities of pleasure within a certain conveyor-belt religious order.

—Anton Vidokle, artist and co-editor of e-flux journal