On Physique Magazine Photography

In Aperture magazine #187, from 2007, writer Vince Aletti reflected on early twentieth-century physique magazines, a genre of men’s fitness publications that became a de-facto source of gay erotic photography as early as the early 1900s. During a time when homosexuality was considered scandalous and American obscenity laws prevented the publication of provocative photographs, physique magazines served as a veiled source of homoerotic imagery, serving a largely closeted audience. To coincide with the release of Aperture magazine #218, “Queer,” we republish an excerpt of Aletti’s look at this overlooked, and in some cases, purposefully obscured, area of photographic history. This article first appeared in Issue 3 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

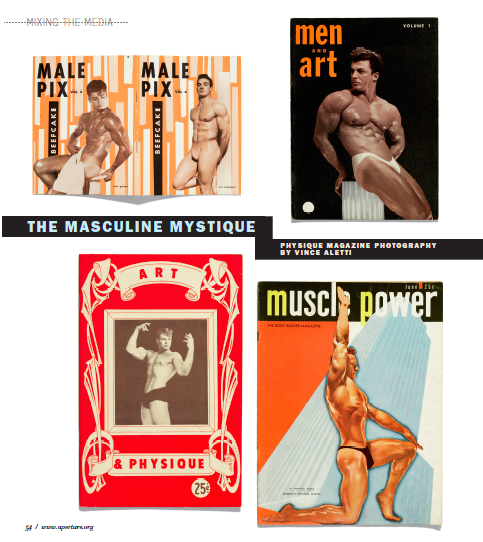

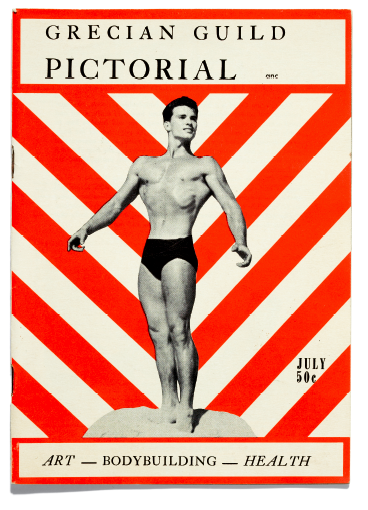

The magazines on these pages were produced for an audience that their publishers never named and rarely acknowledged; in a sense, they were as closeted as many of their gay readers and even more vulnerable to discrimination and attack. Muscle magazines like Vim, Superman, Strength & Health, and La Culture Physique, some of which date back to the early 1900s, were the first to feature photographs of nearly naked men, but they were all professional and amateur bodybuilders, and their display was intended to inspire sportsman-like admiration and emulation, not prurient interest. Although the physique magazines that began appearing in the mid 1950s—including Art & Physique, Physique Artistry, Men and Art, Body Beautiful, and Adonis—also printed photographs of Mr. America contestants, the emphasis shifted, ever so subtly, from sport to sex. But if these new, pocket-sized magazines were more frankly erotic than their muscle-builder peers, they weren’t about to admit it.

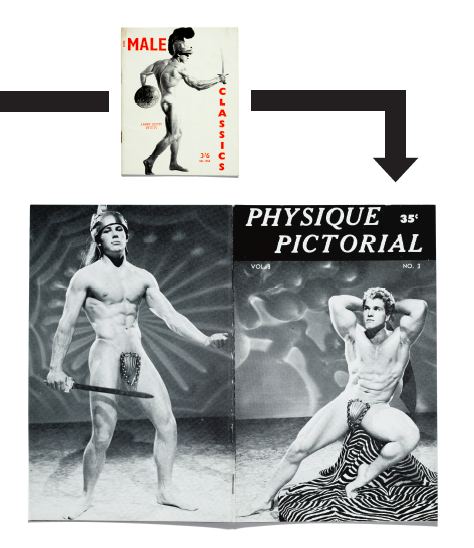

Most of them covered their metaphoric asses with statements announcing their high-minded intentions. A note in a 1954 issue of Physique Pictorial claimed its collection of preening male nudes was “planned primarily as an art reference book and is widely used in colleges and private schools throughout the country. . . . Several psychologists and psychiatrists have told us that books such as Pictorial often have a highly beneficial effect on negative, withdrawn patients who become inspired by the extrovert enthusiasm and exuberance of healthy, happy athletes.” Other publications prided themselves on combining self-improvement and art appreciation: articles titled “Are Bodybuilders Oversexed?” and “Sex Fears Probed!” and rudimentary exercise instruction appeared alongside photographs of Greek and Roman statuary and “art studies” of handsome young men wearing the polyester equivalent of the classic fig leaf. Still, it’s hard to believe these magazines ever passed for straight; they certainly didn’t fool their queer readers.

To be fair, physique publishers weren’t being cowardly, merely circumspect. Despite an incipient movement for gay liberation and visibility (the Mattachine Society’s magazine, One, began publishing in 1953), homosexuality was still a scandal in the 1950s, and American obscenity laws tended to keep its photographic representation either furtively underground or heavily coded. Photographers and publishers could be arrested if a model’s pubic hair was not sufficiently airbrushed out of the picture or the bulge in a posing strap was too clearly defined, and any hint of affectionate contact between men was strictly policed.

The look of physique work from this period wasn’t entirely a matter of wary self-censorship, however. Many photographers in the field (some of whom had begun their careers in muscle mags) had a keen eye, a refined sense of their craft, and strikingly individual styles. Surely most of them were aware of the artistic precedents set by Thomas Eakins, Eadweard Muybridge, and F. Holland Day, and more contemporary examples of male nudes by Edward Weston, Herbert List, Minor White, Imogen Cunningham, and George Platt Lynes would not have been hard to come by. (Lynes’s most frankly homoerotic work wasn’t published until after his death, and it springs from the same hothouse atmosphere of repression and rebellion that inspired the headiest physique photographs.) Much more obvious precedents were the turn-of-the-century photographs of Wilhelm von Gloeden, Guglielmo Pluschow, and Vincenzo Galdi, whose sepia-toned pictures of Italian peasant boys posing with panpipes and classical drapery were widely circulated in the gay underground. The American studios tended to cling to an equally mannered, obviously commercial tradition as much from an impulse to idealize and romanticize the nude as from a need to redeem it.

Physique photographers used props that evoke the classic nude—fluted columns, elegant drapery, “marble” pedestals—in order to nudge their teenage bodybuilders, amateur athletes, and tattooed Marines into the realm of Art even as they hovered on the brink of pornography. To update the classical ideal, they drew on the conventions of Hollywood glamour photography (the dramatic lighting, the prominent prop, the “thoughtful” stare into space), the standard muscleman posing repertoire (including the requisite gloss of body oil), a butched-up version of the vocabulary of gesture and attitude found in fashion magazines, and pieces of the hyper-masculine wardrobe fetishized in the same period by Tom of Finland: denim jeans, motorcycle boots, leather jackets, jockstraps, hard hats. The resulting images were at once stylized and subversive, way over the top and just under the radar.