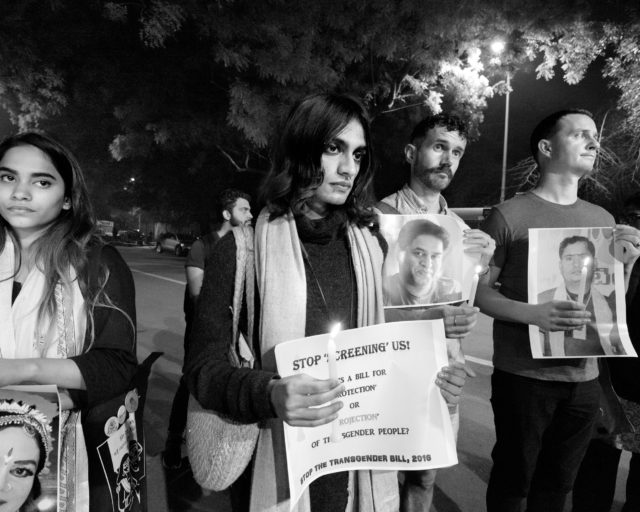

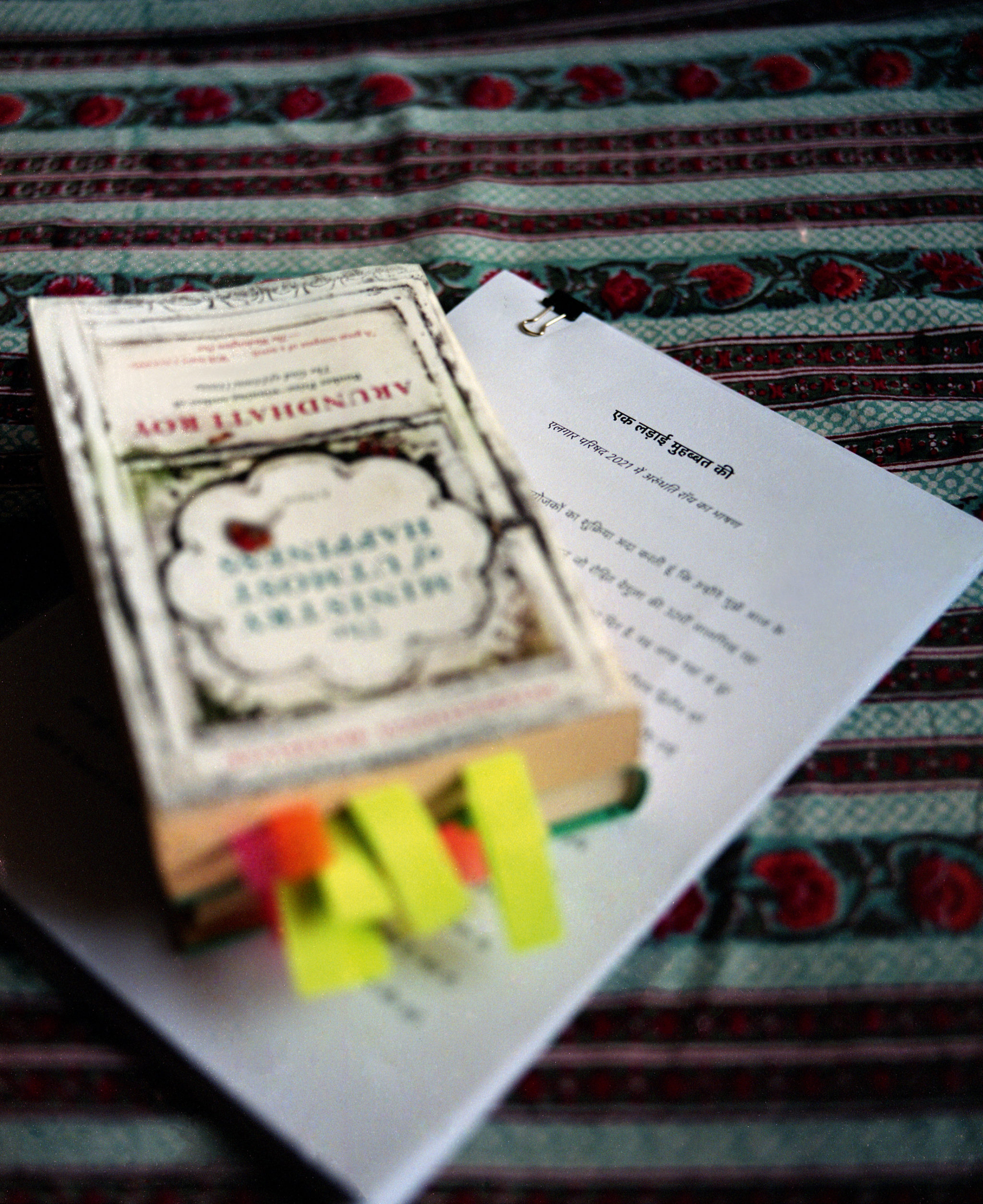

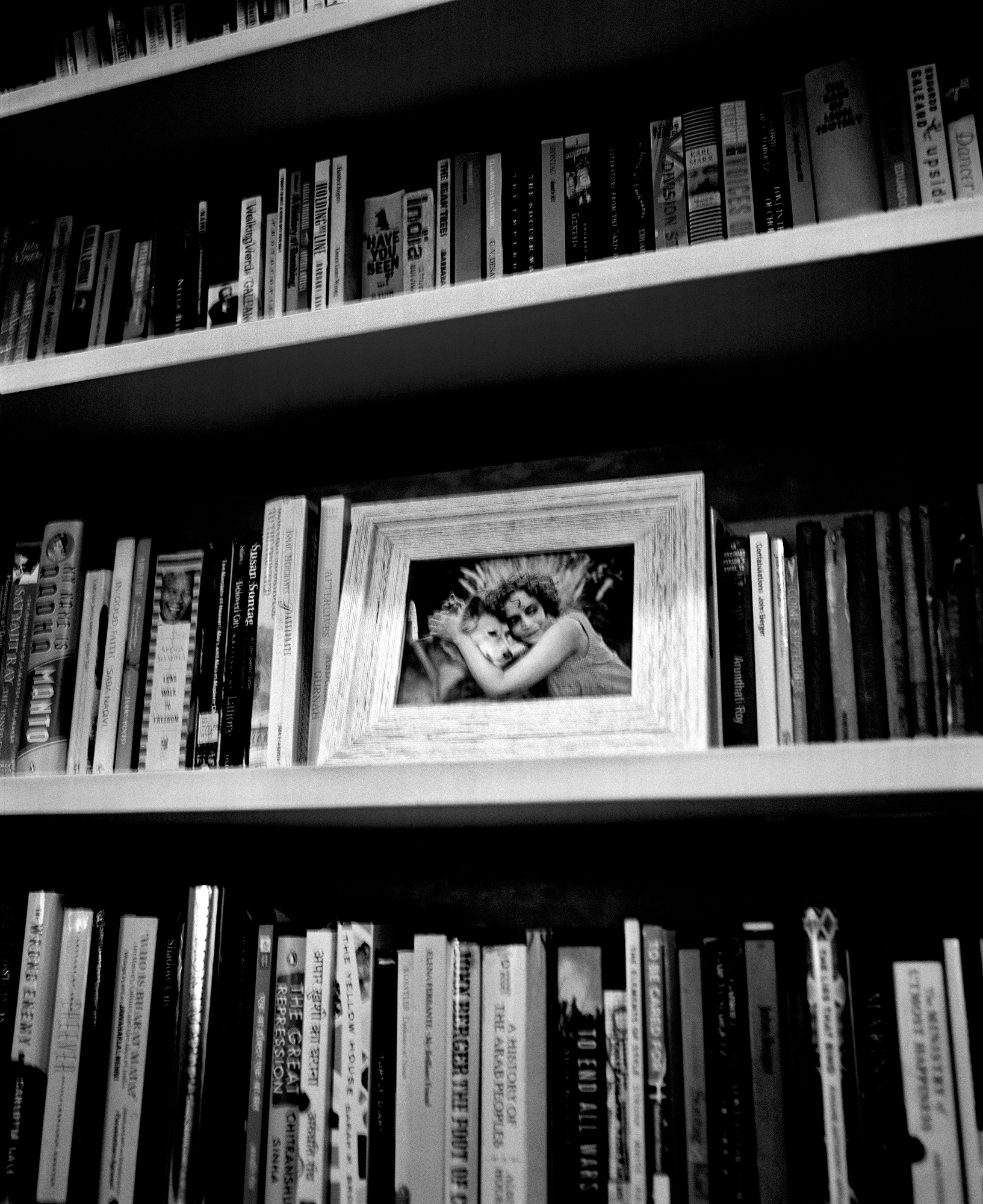

Arundhati Roy, New Delhi, February 2021

Photograph by Ashish Shah for Aperture

“A novel gives a writer the freedom to be as complicated as she wants—to move through worlds, languages, and time, through societies, communities, and politics,” Arundhati Roy recently wrote. Having risen to international fame with her Booker Prize–winning novel The God of Small Things (1997), Roy is a singular voice in contemporary literature, producing riveting works of fiction, along with a prodigious output of essays that address class, gender, and politics with a moral clarity and urgency that reflect her role as a committed activist.

Born in a small town in Northeastern India and raised in Kerala, Roy moved to Delhi to study architecture, a background that would shape her work as a writer. Here, the filmmaker and essayist Shohini Ghosh speaks with Roy about the links between the space of a novel and the built environs of the city as well as the political crises and large-scale farmers’ protests that have shaken Delhi and reverberated around the world. Their conversation is illustrated with images by Mayank Austen Soofi, known for his popular Instagram account called “The Delhi Walla,” and a photographer whom Roy considers to be one of the city’s finest, most tender chroniclers. (This conversation took place before the second COVID-19 wave hit India. Read more from Roy on the impact of the health crisis.)

Photographs by Ashish Shah for Aperture

Shohini Ghosh: How did you end up coming to Delhi?

Arundhati Roy: It was a well-plotted escape from the village and the small town nearby where I grew up in Kerala. As a child, I was surrounded by concentric layers of fear and dread that came from within my home and family as well as from the community. My mother had married “outside” her community—the very closed, casteist, moribund, and elite Syrian Christian community of Kerala—and then she had committed the double crime of getting divorced. So my brother and I, while we did not belong to any socially oppressed caste or community, were made to understand, in a million different ways both subtle and crude, that we did not belong in the home we lived in or the society to which my mother’s family belonged. To me, the message was clear: “Nobody will marry you.” It made me feel, from a very young age, Why the heck would I want to belong? Why would I want to marry any of you? I yearned to escape.

Ghosh: How old were you?

Roy: I fled in 1976, when I was sixteen. I knew I needed to get an education that would make me financially independent. I chose to study architecture. I had been deeply impacted by the ideas of the architect Laurie Baker, who built the school my mother founded and continues to run. I studied there for many years. “No-cost architecture” is how Baker described his work—the most beautiful buildings that were built so cheaply that they threatened the building industry. So at sixteen, as soon as I finished high school, I was on a train to Delhi to sit for the entrance exam to SPA, the Delhi School of Planning and Architecture. The journey was three days and two nights long . . . and I arrived in a different world. When I turned seventeen and was in my second year, I stopped going home. I never went for years. I worked my way through college—of course, I could do that then. Now, things have changed. Now, higher education is closing its doors to those who have no money. Every day, I feel gratitude to this city that liberated me. Now, I do go back home to Kerala. Those old wounds have healed, but they still lurk close to the surface of my skin.

Ghosh: What images of the city do you most remember from that time?

Roy: I remember the excitement of pulling into the railway station. The smell of freedom and the excitement of anonymity. Anonymity is impossible in villages and small towns in India. For me, that was the greatest gift anybody could give me. The infinite possibilities of naughtiness. I was so ridiculous though. When I first arrived, I had no sense whatsoever of the scale and size of a big city. So I went to the auto- rickshaw rank at the railway station and asked a driver if he could take me to Mrs. Joseph’s house. I still laugh out loud when I think about it. Mrs. Joseph was my mother’s sister—a good and decent Christian—who lived in Delhi then. I was to stay with her. She wasn’t thrilled about her nonpedigreed niece’s arrival and made that very clear. So I made it a point to inflict myself and my indecency on her as often as I could.

I was also very frightened of the city. This is because of the films I saw growing up. At the time, in virtually every Malayalam film, the heroine got raped. The rape was always lovingly choreographed, in elliptical ways . . . reflections in the ceiling fan, flowers dropping off their stalks, or whatever. Utterly destroyed women. As a result of this, I grew up believing that every woman gets raped. It was just a question of where and when. So in that auto rickshaw, on my way to Mrs. Joseph’s house in Delhi, I clutched a knife hidden in my bag. I was fully prepared to meet my womanly future. The first few days in the city were intimidating . . . but then . . . the school of architecture. Anarchist heaven. I knew I had escaped forever. I would be safe in a dangerous sort of way.

Ghosh: Before you wrote The God of Small Things, you wrote two screenplays: In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1988) and Electric Moon (1992). Did the city play a role in shaping you as a writer?

Roy: In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones is about students in architecture school—stoned, bell-bottom-wearing hippie kids in the 1970s. Annie is actually a man, Anand Grover, who is repeating his final year for the fourth time, the victim of one professor’s vendetta. Annie’s a little eccentric, a little defeated. He rears chickens and rabbits in his hostel room and is obsessed with how to handle what he calls “rural–urban migration.” Although I opted for architecture because of a kind of desperation to begin to earn a living, the five years I spent there have laid the foundation for the ways in which I see and think.

By the time I was in my final year, I was almost as interested in urban studies as I was in architecture. My thesis was not a design thesis. It was about the city, postcolonial Delhi, how it came to be what it is, what it does to the people who live in it. The city and the noncity. The citizen who is welcome and for whom the city and its laws are made.

The noncitizen who is unwelcome and lives in the cracks between institutions, who subverts laws as well as the imagination of the urban designer. Who shits on top of the sewage system. That lens, that way of looking at our cities, has remained with me through my screenplays and my novels. To me, the city was and is a fascinating, never-ending story. It’s a novel with characters who appear and disappear, shaping the physical space around them.

Ghosh: When you wrote The God of Small Things, you were living in Delhi and writing about a place that was far away in space and time. How did that work out?

Roy: It didn’t seem to matter one bit. The village I grew up in, the pickle factory, the landscape, the people, the green river, the coconut trees that bent into it, the broken yellow moon reflected in it, the flash of fish—I am made up of all that. I am that. No matter where I go. I knew every plant and worm and fish and insect; they were characters in my life. As oppressive as the humans around me were when I was growing up, the river and the insects, the rain and mud were my pals. But perhaps the physical landscape of Kerala was conjured up more vividly in The God of Small Things because it was so different from the place that I was living and writing in.

Ghosh: For me, the experience of reading The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was like learning to navigate a copious landscape. In one of the chapters in the book, a character called Khadija takes one of the protagonists, S. Tilottama (or Tilo), on a journey across a city in Kashmir. They travel, and I quote, “through a maze of narrow, winding streets in a part of a town that seemed to be interconnected in several ways—underground and overground, vertically and diagonally via streets and rooftops and secret passages—like a single organism. A giant coral or an anthill.” This could well be a description of the teeming metropolis that is Utmost Happiness, in the alleyways of which the many interconnected narratives of the novel unfold. Did your training as an architect and urban planner have an impact on structuring the novel?

Roy: Yes. The city as a novel—the novel as a city. Truly, I think like that. And I don’t just mean the physical landscape of both cities and novels. I mean it more in the manner of how something is designed, and then that design is subverted, ambushed, enveloped, and turned into something else, and then all of that becomes a part of another design, and on it goes. Something like the way the shapes of cities inscribe themselves spatially on the surface of the earth as distinct from the amorphous countryside that surrounds them. They have a form, a logic that is not immediately obvious, except, of course, imperial cities that were created by fiat and decree. But those, too, are subverted. In the novel, too, this happens often to the narrative. And yet, it’s only once you begin to live in the novel-city of Utmost Happiness that you understand that the apparent chaos is designed. It, too, has its underground, overground, and diagonal pathways that interconnect. It has its own complicated logic.

If you remember, there is a passage in which Tilo thinks about the city . . . It’s a sort of wakeful reverie. She thinks of cities like starlight traveling through the universe long after the stars themselves have died— “fizzy, effervescent, simulating the illusion of life while the planet they had plundered died around them.” So there’s that awareness not just of the city, but of the meaning of the city. Right now in Delhi, the confrontation between the city—the seat of political and economic power—and the countryside, and the plundered planet is playing out in a literal way. As we speak, millions of farmers have risen in protest against three new farm laws that will put the levers of control of Indian agriculture in the hands of major corporations. Over the last twenty years, hundreds of thousands of farmers caught in a debt trap have committed suicide, many by drinking the pesticide they are being forced to use to grow crops that the market wants but their land does not support. And now, with these new laws, they are facing an existential crisis. Hundreds of thousands of farmers have arrived on the outskirts of Delhi. It’s being called the biggest protest in human history. The government has barricaded the city with concrete barriers, concertina wire, and iron spikes, and the area is being patrolled by thousands of police and paramilitary. The borders are no longer just national borders. New battles are unfolding. In Utmost Happiness, those conflicts are folded into one another—the freedom struggle in Kashmir, the rise of Hindu nationalism in India, and the many conflicts, environmental and political, that are displacing and devastating people in myriad ways. All these are connected to one another like a maze of city streets.

Ghosh: In its magnificent embrace of people (living and dead), creatures (birds, mammals, bugs), and places (from the dystopian to the paradisal), Utmost Happiness imagines a world where the nonhuman is integral. Even in The God of Small Things, the world in which the narrative unfolds is as important as the protagonists themselves. In your universe, it seems to me, the human predicament is inextricably linked to the nonhuman.

Roy: Not everybody notices that, actually. I remember somebody telling me that she thought the hum and scurry of insects and other creatures in The God of Small Things were like a background music score. She could hear them. I am incapable of looking at the world, or even thinking about it, with only humans at its center. How can we take anything—any discourse, any ideology, any religion even—that is exclusively about human beings seriously? It’s a sort of violence. A futile, blinkered, foolish violence.

Of course, in The God of Small Things, the landscape and its nonhuman populations wrap themselves around the human protagonists. But even in Utmost Happiness, the nonhumans are an integral part of life. There is so much nonhuman activity even in our most densely populated metropolitan cities, and it’s not just pets on leashes. There are crow conferences, street-dog conclaves, horse confabulations, monkey madness. All you have to do is keep your eyes and ears open—and yes, your heart too—and whole other cities and city-stories will make themselves known.

Ghosh: The COVID-19 pandemic and the complete lockdown in March 2020 transformed the images and imagination of the city. As a majority of the inhabitants locked themselves in, you ventured out into the streets. What did you see?

Roy: I saw what the rest of the world saw, except not just on my cellphone screen. When Modi announced the world’s strictest, cruelest lockdown, giving 1.3 billion of us just four hours’ notice, it became obvious that he had absolutely no idea about the country he is the prime minister of. He was just copying what was being done in the United States and Europe but in a more authoritarian, autocratic way. The previous week, he had asked people to come out on their balconies and bang their pots and pans and ring bells! Like people had in Europe. How many people have balconies in India? It was ridiculous. Lockdowns in affluent Western countries were to enforce physical distancing. But here in India, in the densely populated slums and shantytowns, it enforced the opposite—physical compression. The day after the lockdown was announced, India spilled its terrible secrets for the world to see. Millions of working-class people hidden away in the crevices of big cities—the noncitizens of my architecture thesis—working for a pittance in informal, unregulated jobs, found themselves out of work, unable to pay rent for the cramped tenements they lived in. A mass migration began—biblical in its scale. Millions of workers and their families began walking thousands of miles home to their villages. On the way, they were beaten by the police, hosed down, killed by trains as they walked on railway tracks, held in containment camps. As soon as I saw the streets of our city turn into this river of COVID refugees, I went out. I saw the scenes on the Delhi–Uttar Pradesh border. I walked part of the way with some of the walking people.

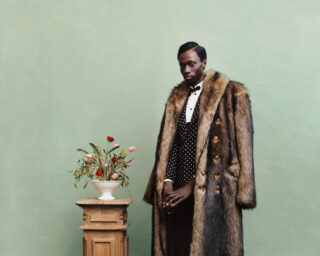

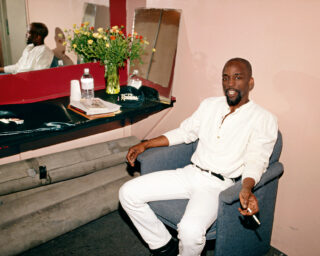

All photographs courtesy the artist

Ghosh: Well over a year later, what has been the consequence for the city?

Roy: The result of this lockdown that wasn’t a lockdown is that the virus spread across India. Fortunately, it hasn’t proved as devastating or as fatal as it has been—and continues to be—in more affluent countries. But the lockdown caused an already severely slowing economy to crash. The urban economy collapsed. India’s GDP shows deep negative growth. In all this devastation, even though agriculture is generally in crisis, during the COVID pandemic, farmers continued to work their fields, so we did not have a food-production crisis. But if all this awfulness isn’t enough, now farmers, too, have been dealt a blow from which they may not recover. Unless we all stand with them and force the repeal of these new laws. So here’s the latest chapter in the story-city and the city-story. Last year, millions of workers were forced to leave the city. This year, millions of farmers have arrived at its outskirts. Between these two events lies an epic tale. The story of our times.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Looking Out/Looking In: Delhi,” under the title “Arundhati Roy: The City as a Novel.”