Dispatches: Athens

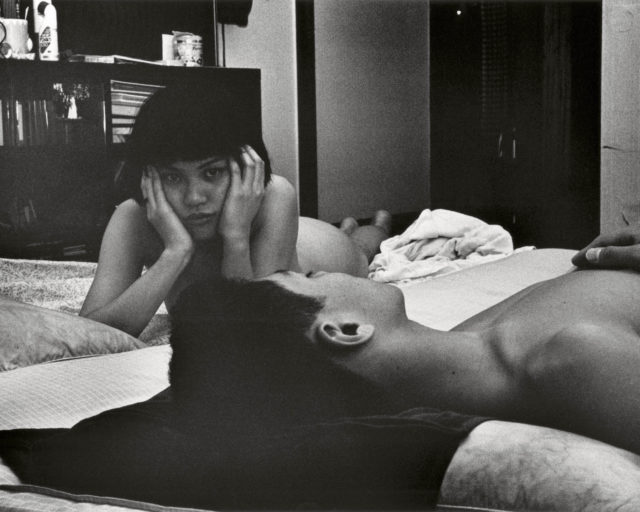

Georges Salameh, Broken Nose, 2012, from the series Spleen

Courtesy the artist

Art flourishes in times of adversity. In the charged political landscape of Athens, austerity measures and the prevailing division in the European Union have taken an irreversible toll on the city often referred to as the cradle of democracy. Yet, there is a pulse of creative inspiration and artistic production. On ghostlike streets where businesses are closing down and rental signs are ubiquitous, new artist-run spaces have emerged and collectives are being formed.

Depression Era is one of the products of this condition. Formed in 2011 and with almost thirty members to date, the collective operates in a unique format: its members are professional artists, photojournalists, architects, activists, and filmmakers who are joining forces in their free time. By resurrecting and embracing the value of communal ideals, strangers from different backgrounds and disciplines come together to experiment collectively—a configuration quite unknown to the mantra of neoliberalism and individualism heard throughout the art world.

Kostas Kapsianis, Watchdog, 2012, from series “Bliss”

Courtesy the artist

The idea was born at the onset of the Greek crisis by the photographer Pavlos Fysakis, who was drawn to the artwork being produced in Greece at the time and looking for a way to tie it all into an action. Fysakis started inviting people to come together, and the invited ones, once they joined, could then invite others. The group began having conversations about their work and the need to depict the hidden reality of their city as they were experiencing it themselves, versus the Athens being portrayed by foreign and domestic media. Their gatherings soon led to exhibition opportunities. As they characteristically state, their mission is to “document our own downfall rather than someone else doing it for us, in this colonialist-style ‘crisis supermarket’ the country has turned into.”

Eirini Vourloumis, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, November 2013

Courtesy the artist

From Eirini Vourloumis’s photographs of ministry interiors and Georges Salameh’s peripatetic discovery of overlooked urban scenes to Kostas Kapsianis’s upscale suburbia and Marinos Tsagkarakis’s abandoned beach bars, the result is a diverse mapping of the city. Despite its range of individual sensibilities, the collective’s vision manages to meet at the intersection a nostalgic longing for the past and the symbolic interpretation of the living present, producing an ironic commentary and an inescapable projection of a future promise.

“The making of culture produces politics,” Fysakis explains. It was vital, then, for Depression Era to channel their production of knowledge appropriately, which led to the group’s action being directed toward “infiltrating the system and the institutions” rather than adopting conventional activist action formats, like public protests or local interventions. At the 5th Thessaloniki Biennale in 2015, for example, Depression Era exhibited a project compiled of their own work mixed with images by participants who had taken part in their workshop series earlier in the year, some of whom had never been exhibited before. The strength and power of the group lies not only in their individual artistic practices, but in the collective effort made for those practices to be exhibited within a dismantled and censored sociopolitical context, where opportunities to be heard are nonexistent. The empowerment generated via their ability to speak out provides a platform upon which disillusionment, insecurity, and despair transgress into a sense of clarity and transparency for the present moment.

Yiannis Theodoropoulos, Skiros from the series Greek Party, 2004

Courtesy the artist and AD Gallery, Athens

Members of Depression Era, including Fysakis, George Moutafis, Tsagkarakis, Maria Mavropoulou, Kapsianis, and Pasqua Vorgia, could also be found at last year’s Athens Photo Festival (APF). APF, an institutional synecdoche of the photographic world, is the first private festival in the country and the fifth oldest photography festival in the world. Initially conceived in 1987 as a biennial with support from the state, APF is now annual and scarcely self-funded; its committed team, led by Manolis Moresopoulos, is mostly compensated by the pride of accomplishing something otherwise impossible. With other similar photography initiatives having tried and failed to sustain themselves in Greece throughout the years, APF’s ability to successfully establish its presence within the international scene is also a reflection of photography’s historic trajectory in the country, as the medium slowly began to be considered fine art in the 1990s.

Just as APF’s development testifies to photography’s development in Greece, so does Depression Era’s nomadic and diasporic circumstance act as a reflection of the political climate. With a growing institutional presence and educational action in the form of seminars and workshops, Depression Era uses art to chronicle an honest and untold story of the city’s urban landscape. Rendering an alternative visual archive of contemporary Athens, Depression Era attests to this nation’s uncompromised free spirit.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.