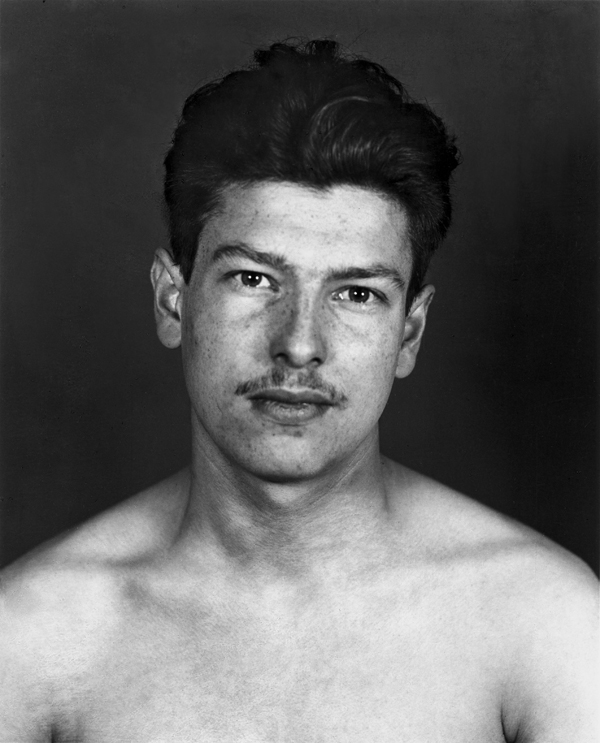

August Sander, VI/44a/7 Political Prisoner Portfolio VI/44a—The City, Political Prisoners, 1943

In December 1941, Adele Katz sent a postcard that was never received. “My two dears, first of all let me send you my very best wishes,” she wrote from the Litzmannstadt ghetto, in the Polish city of Łódź. “I’m sorry to say that so far we have waited in vain for news from you.” Adele’s father, Benjamin (Benno) Katz, had been a prosperous butcher and meat wholesaler in Cologne, having opened his business in 1892 not far from the home and studio of the photographer August Sander. But on April 1, 1933, the day of Germany’s first nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses, Benno and his son, Arnold, were forced to march the streets of Cologne carrying defamatory, anti-Semitic signs. It was a scene of humiliation.

Soon, the family business would become untenable; several years later, unable to go abroad, Benno and Adele were sent to the Łódź ghetto. By May 1942, just months after Adele wrote her postcard from Łódź, she and Benno were deported to the Chemno extermination camp and killed.

This is not how a story about August Sander—the Rembrandt of photography, whose name summons classical archetypes of German identity between the wars—is supposed to start. How do the Jews fit in? But the German Jews who Sander photographed in the late 1930s, among them Benno Katz and his family, are at the center of August Sander: Persecuted/Persecutors, People of the 20th Century (Steidl, 2018), an extraordinary book that accompanies an exhibition of Sander’s portraits at the Mémorial de la Shoah, the Holocaust museum in Paris. Numerous photographic collections have put faces to 180,000 German Jews killed during World War II, as Sophie Nagiscarde, head of the cultural department at the Mémorial, notes in the introduction. But “none compare with August Sander’s skillfully produced portraits of the Jews who sat for him in his studio.” And none, perhaps, have been collected and printed with the austere clarity of this book, with its fragrantly inky, unvarnished pages, which was overseen by Gerhard Sander, the photographer’s grandson.

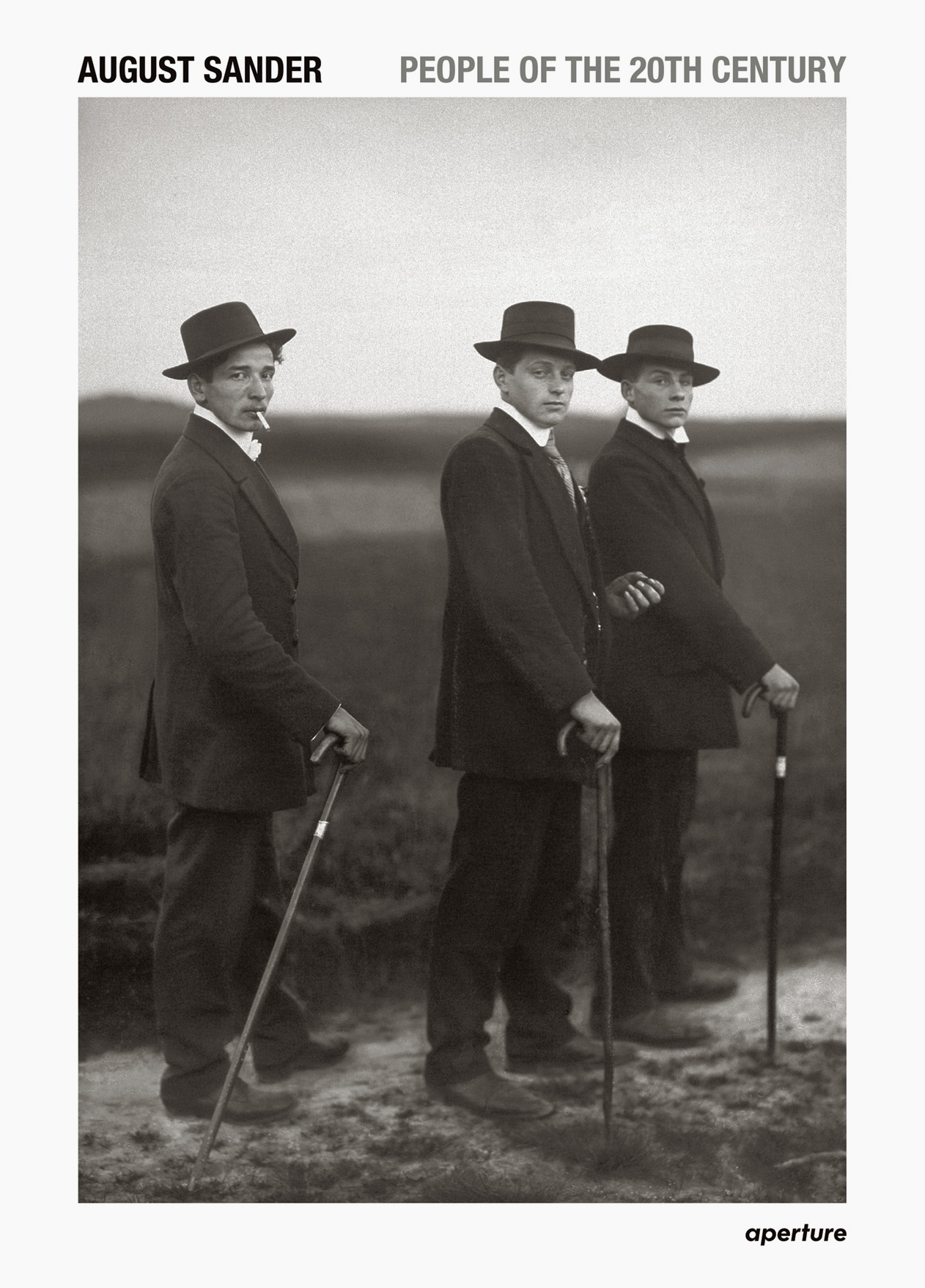

Persecuted/Persecutors unfolds with the graceful structure of a sonata: exposition, development, recapitulation. In the beginning comes Face of Our Time, the 1929 photobook that would precede Sander’s masterwork, People of the Twentieth Century. Taken in the German Westerwald region and in Cologne, Sander’s portraits, as he gathered them into highly organized portfolios, were meant to portray the breadth of humanity through individual faces and bodies marked by a person’s station in life. Here, Young Farmers (1914), Country Girls (1925), Pastry Cook (1928), Working Students (1926), and Tycoon (1927)—some of the most memorable photographic portraits in the history of the medium—are set at quarter-page size, as aides-mémoire. We know them, but they’re not the stars this time. They remind yet again of Sander’s brilliance, and a time when making a photograph was an event, not a habit.

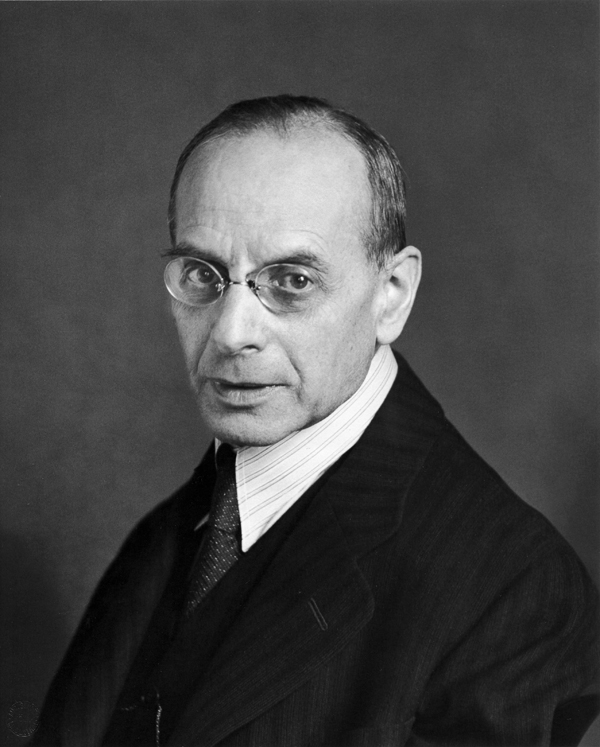

There follows an entirely black spread, the silence before the next movement: “Portfolio IV/23a—Classes and Professions, The National Socialist.” Across ten pages are masculine exponents of the Nazi regime, each at full-page and uninterrupted by any text. They are members of the SS or Hitler Youth, according to the captions in the back matter. Some, in their looks, edge close to Aryan deities; others, with their glasses and well-kept hair and pudgy middles, look like someone’s father or brother. NS insignia is apparent in subtle or glaring ways, as in Sander’s portrait of the Nazi head of the department of culture, seated in profile, a pose that foregrounds the swastika on his armband. “Since millions of Germans from all social backgrounds abhorred it, the Nazi armband was meaningless,” Alain Sayag, of the Centre Pompidou, writes in one of the book’s many wide-ranging essays. “Similarly, the Nazi uniform, authentic or costume, became a hollow symbol: the mask behind which an entire society was hiding.” But it’s not the Nazi accessorizing that makes the portraits in this portfolio unnerving. It’s the hands, calm and carefully folded, a wedding ring shining—or, in one fearsome young National Socialist, wide-spanned and clenched, veins popping. Those hands are capable of anything.

With comparative precision, the persecuted share this book with their persecutors. “Portfolio VI/44—The City, Persecuted” is a collection of studio portraits of German Jews, most taken in 1938. They appear pensive, guarded, their minds are elsewhere. They were having their ID portraits made; they were thinking of escape. Persecuted/Persecutors tethers these plates to biographical research conducted by Cologne’s NS-Documentation Center. Brief and empathic in tone, and printed on light blue pages in the appendix, the stories of the persecuted are often accompanied by transcriptions of letters. Many end with a chilling cadence about deportation. Philipp Fleck, for instance, an editor of a bis z, the magazine of the influential Cologne Progressives with which August Sander was associated, died in the Lódz ghetto in 1942. He never received the letter his brother, Richard Fleck, sent in May of that year. “You can imagine how I long for some news of you,” Richard wrote. “I hope you are, at least, in good health.”

Of the Nazis, we learn nothing.

Apart from the exceptional reproduction of the plates, the revelation of Persecuted/Persecutors comes in the form of the contact prints from which Sander selected the twelve images for the portfolio “The Persecuted” in People of the Twentieth Century, as well as various other ephemera (letters, book covers, archival photographs) that are threaded throughout. The contact prints are set to scale, with full negative frames, on a pale gray-green background, and pull back slightly to reveal the apparatus of the studio. They lose none of the intensity of the final cropped versions. Adele Katz appears in profile with her white blouse and watch, alongside her brother, Arnold, with his wide-lapelled jacket and the still-youthful openness of his features.

This sequence concludes with smaller 6-by-9- centimeter contact prints of Erich Sander, August’s older son, who was imprisoned in 1934 for his political activities with the Socialist Workers’ Party. Erich, who died in prison in 1944, became a prison photographer, and several of his own portraits of political prisoners would be integrated into his father’s work in “The Persecuted.” A leitmotif in Persecuted/Persecutors, the unexpectedly moving relationship between father and son, between master and protégé, finds its most eloquent expression in a photograph of August at his desk, two years after Erich’s death. On the wall are five portraits of Erich, including one from his student days, recognizable from Face of Our Time, and one of his death mask, included in Sander’s final portfolio, The Last People.

All photographs © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Köln; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; ADAGP; and courtesy Galerie Julian Sander, Cologne and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

“Last week I was again busy with Menschen des 20. Jahrunderts,” Sander wrote, in 1947, of his intention to include the persecuted in his portfolios. “We got the Jew folder down on paper. These are people who emigrated or breathed their last in the gas chambers. All magnificent heads of unpolitical people.” Sander aspired to make a portrait of society as it was, not as it could or should be. The pictures might well have been enough. But, the cumulative effect of the research and short biographies of the Jewish subjects and political prisoners in Persecuted/Persecutors, arriving at the end of this book like a coda, is devastating. No longer “types,” Sander’s subjects are envisioned here as windows onto individual lives brutally cut short. Adele Katz’s letter was never received because it was intercepted by the Nazis. She is alive now only in a photograph, but her words, at last, can be read by an audience she might never have imagined: “Heartfelt greetings and kisses from me, and say hello to everyone who knows me.”

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 015 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.