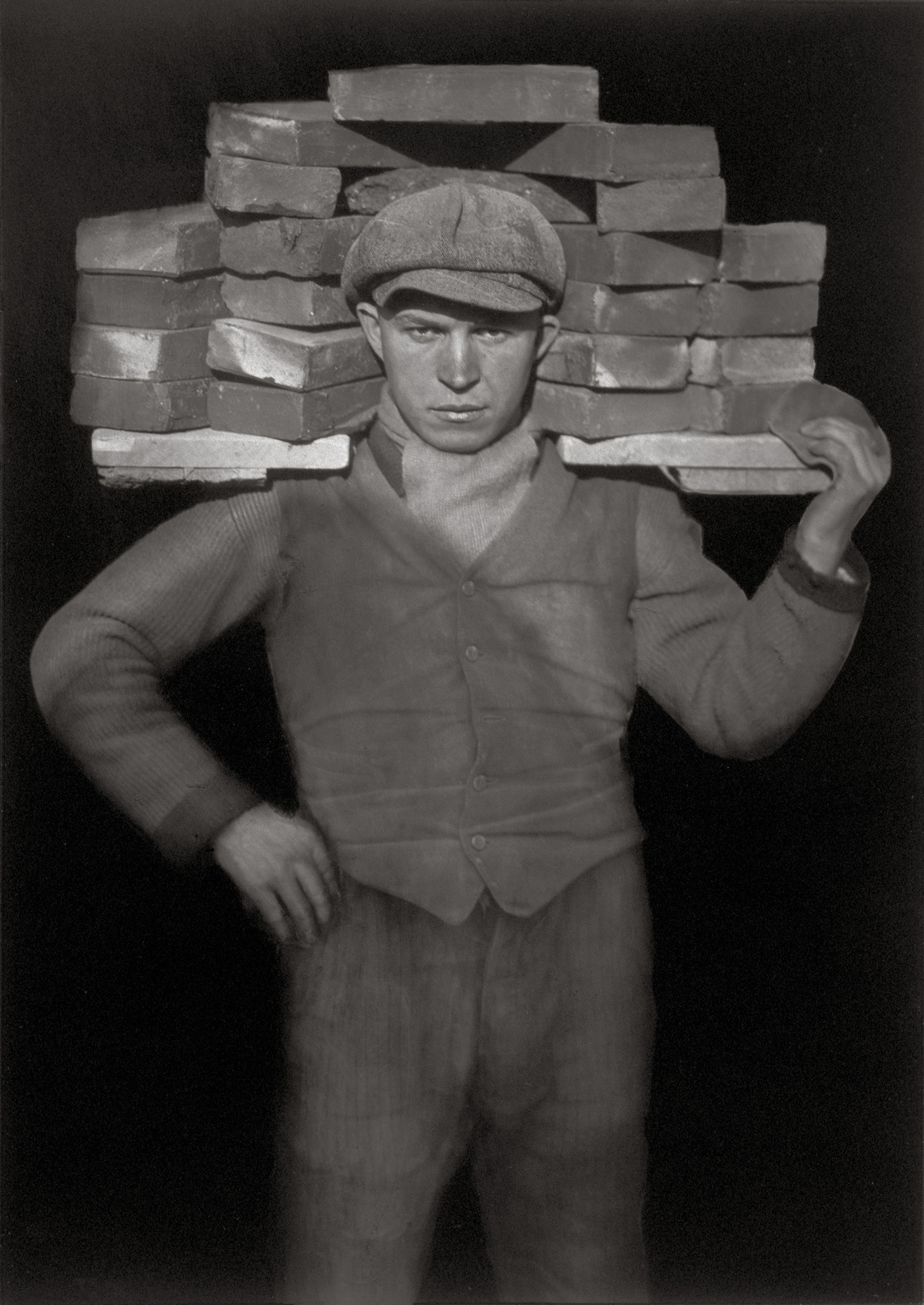

August Sander, Bricklayer, 1928

August Sander’s profound influence on the history of photography is impossible to overstate. But, in the mid-1970s, when Aperture published a volume of his work, only a handful of books on the German photographer’s work were in print. Exhibited in New York for the first time, the prints made by Sander’s son, Gunther, for the Aperture monograph are the subject of an exhibition at New York’s Deborah Bell Photographs, which features some of the most iconic portraits of the twentieth century.

In 1977, Aperture published a slim volume of photographs by August Sander, for the seventh entry in the Aperture History of Photography Series. With a selection of forty-three portraits from the German photographer’s expansive, early twentieth-century study of German society, the Aperture book was then one of the few available introductions to Sander’s work. At the time, his son Gunther Sander had prepared a set of prints for the bookplates, following his father’s technique. The younger Sander deposited the prints in Cologne with Könemann, the publisher of the German edition, and they were soon forgotten. More than thirty years later, after their discovery in a private collection earlier this year, Gunther Sander’s prints are now the subject of a jewel-box exhibition at Deborah Bell Photographs in New York.

August Sander was born in 1876 in Herdorf, a mining region near Cologne. In his youth, as an apprentice to a foreman, Sander was chosen to assist a landscape photographer contracted by a local mine. He soon became fascinated by photography. After a stint in the army, he worked for a photographer in Linz, Austria, and later bought the studio. By 1910, having returned to Cologne, Sander began cycling around the rural lands of the Westerwald to make portraits of local farmers and tradespeople. These images, the first entries into Sander’s prolific catalogue of German types, display the clarity and precision that would later become the hallmarks of New Objectivity, a Weimar-era artistic response to the chaos of World War I.

Prior to Aperture’s monograph, the primary book on Sander’s portraiture was Antlitz der Zeit (“Face of Our Time”), published in 1929 by Transmere Verlag in Munich. Sander intended the sixty images of Antlitz der Zeit to be a preview of his anticipated multivolume series, which would divide his photographs of German citizens into seven major categories and numerous subgroups. In contrast to Antlitz der Zeit, which is sequenced according to the structure of Sander’s portfolios—beginning with the farmer, ascending through the classes and professions, and concluding with the “last people,” the destitute and the dying—the Aperture book contains a populist, illustrative combination of memorable portraits. Many images are masterpieces, ranking among the most iconic photographs in the history of the medium.

The exhibition at Deborah Bell Photographs presents all forty-three prints in the same order as in the Aperture book, elegantly framed and set in the window-mats of pebbled white paper favored by Sander. The modestly scaled images and the narrow salon of the gallery belie the arresting power of the portraits, which collectively provoke a peerless, insatiable curiosity. Seeking to portray every type of German citizen with the same amount of concentration, Sander provided an immensely detailed transcription of German life, from the clothing and hairstyles of the time, to the physiognomy that characterized the conditions of a subject’s working life.

Sander’s lucid approach no doubt owed to his consistent use of glass plate negatives, which allowed for extreme detail. For the expert viewer acquainted with the sociology and material culture of early twentieth century Germany, the images contain a wealth of information to be endlessly scrutinized. The painters, sculptors, musicians, and prominent intellectuals to be filed under “Trades, Classes and Professions” were often identified in later publications on Sander, which opens up the possibility of reading deeply into their work. But, for the unnamed peasants, clergymen, high school students, athletes, and homeless figures, who appear as living sculptures, what can we possibly learn about their inner lives? Though New Objectivity photography aspired to transparency without adornment, Sander’s portraits protect as much as they reveal. Like the comparative industrial studies by Bernd and Hilla Becher, who referred to New Objectivity as a model for their systematic typologies, Sander never goes out of style.

The exhibition, which follows Gerd Sander’s selection, is notable for its differences from the sequence Sander originally chose for Antlitz der Zeit. The indelible classics, Young Farmers (1914) and Boxers (1929), are there, but so is Circus People, Düren (1930), an extraordinary multiracial portrait of seven performers listening to a gramophone, which wasn’t included in Antlitz der Zeit. By the mid-1930s, the Nazi party had declared Sander’s project antisocial, halting sales of the book and destroying the printing plates, ostensibly in retaliation for the resistance politics of Sander’s son, Erich. In a portrait such as Circus People, it’s easy to see how Sander’s democratic vision of Germany, which brought all types into its genealogy, implicitly defied the idealized Aryan body of Third Reich propaganda.

All photographs courtesy Galerie Julian Sander / Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne

For Working Students, Cologne (1926), one of the final images of the exhibition and the Aperture book, Sander photographed his son Erich together with three young men. With its comparative approach, and its voluminous yet subtle range of poses and facial expressions, Working Students is a precedent for Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits of adolescents, Nicholas Nixon’s multi-decade series The Brown Sisters, and Thomas Ruff’s untitled 1980s portraits of artists and friends at the Kunstacademie Düsseldorf. The wake of Sander’s influence is impossible to measure. Sander’s subjects are types and originals, individual and universal. “The portrait is your mirror,” Sander told his grandson, Gerd. “It’s you.”

August Sander: Prints for the Aperture Monograph, Printed by His Son Gunther Sander is on view at Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, through October 31, 2015.