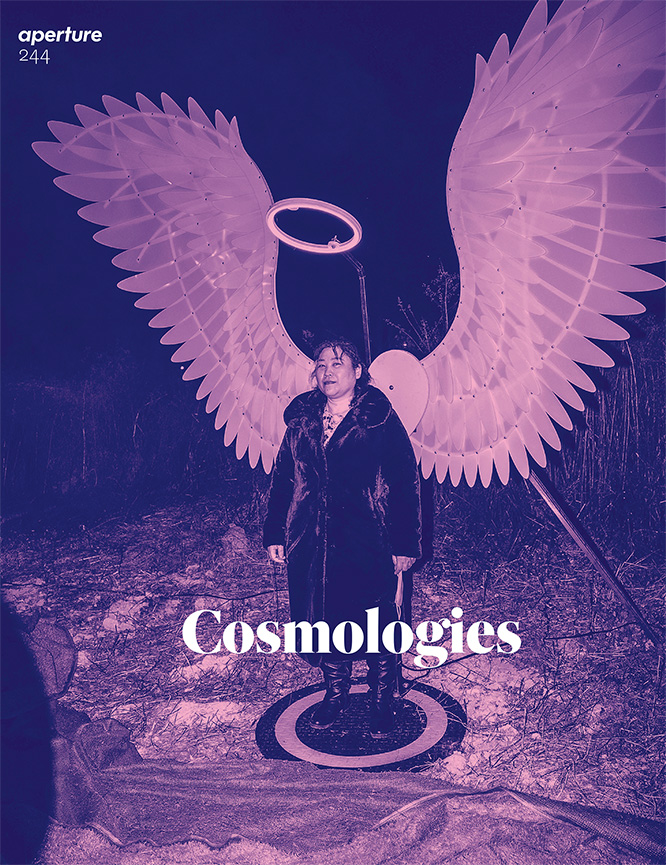

Awol Erizku, Love is Bond (Young Queens), 2018–20

In Awol Erizku’s Jaheem (2020), an African mask is engulfed by fire, an orange-white burn so totalizing that the lapping flames light the steel-mesh fence against which the object is set. Energizing in every sense, Jaheem is a singular image, but the picture also coheres many of the aesthetics and subjects characteristic of Erizku’s multivalent conceptual photographic practice: Africa and its diaspora; the mystical, the spiritual, and the surreal; creation both natural and cultural. High saturate color. Luminosity. Heat.

Fire is not seen but implied in Quotidian Drip (2018–20), the scene bathed in a warm orange, near-red, glow. A still life, the work demonstrates Erizku’s open yet refined embrace of wide-ranging cultural reference points. Leather loafers—one shoe propped up on bricks—meet a Stanley-brand measuring tape, stacks of crisp Benjamins, a single rose stem in a clear vase, alongside a half dozen other dissimilar items. In one art-historical sense, this assemblage can be understood as purposefully nonsensical, engaging traditions of Dadaism and Surrealism. A photographic scrim that a C-clamp would conventionally clasp gets enigmatically replaced by an Ashanti “Akuaba” fertility doll. Behind it, a maneki neko, “lucky cat,” peeks out from behind a jar. To stop at the absurd, however, would risk occluding the ways that Erizku’s arrangements are constructed with intentions toward meaning-making of a kind. The unconventional construction visualizes the syncretism and multiplicity characteristic of contemporary global life, and, perhaps, especially Black creative life: leather, flowers, dollars, labor. At the same time, through selection, placement, and staging, these stable (and ofttimes staid) referents and symbols are cracked open and made anew both ontologically and aesthetically. There is no single reading of any object or juxtaposition, each unfurling along unending chains of signification. A bumblebee is a sartorial flourish . . . an ecological touchstone . . . a simple flash of gold.

This persistent signification is especially true in the case of Erizku’s treatment of cultural objects from the continent. In Quotidian Drip, the faint profile of the Queen Nefertiti bust—ubiquitous within the Western imaging of African cultural import—is enclosed within a semitransparent jeweled cube. Barely visible but resolute, she is both familiar cultural referent and distanced glistening form. In Love Is Bond (Young Queens) (2018–20), Nefertiti is again present, with a quintet of young Black girls encircling a pedestaled bust of the royalty, while playing ring-around-the-rosy. In Erizku’s imaginings, Africa is not only ancient but also mythical, technical, experimental, futurist, innovative, (e)strange(d).

All photographs courtesy the artist and Ben Brown Fine Arts, London

It is also cosmic. In Moon Voyage (Keep Me in Mind) (2018–20), a picture that features two individuals in a ballroom- like embrace, a female figure wears what appears to be a stylized African mask pigmented in blue. Her silk dress and arm-length gloves bring tradition to the image, while the mask presents an electrifying portal to the mythological alien. The energy powering Moon Voyage is not solar but lunar, a green celestial light under which the two dance. But even without fire, the same sensibility that guides work such as Jaheem is present here, as it is in all of Erizku’s still lifes, portraits, and tableaux. It is an approach marked by intuition, style, history, and opacity. A reverence and a confidence. Heat.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies,” under the title “Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax.”