Beyond the Decisive Moment by Ellie Armon Azoulay

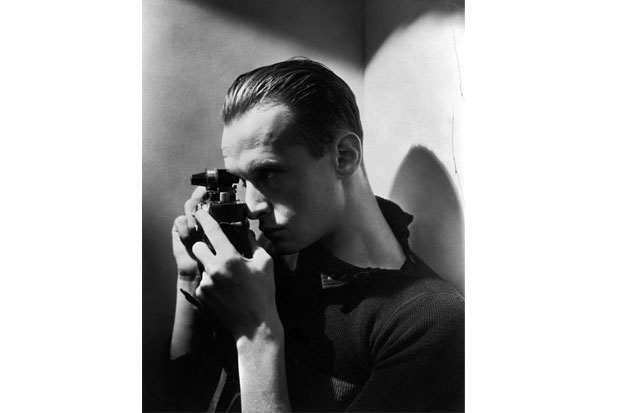

George Hoyningen-Huene, Henri Cartier-Bresson, New York City, 1935

© Collection HCB/FRM/Magnum Photos

The Henri Cartier-Bresson blockbuster retrospective recently on view at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, leaves no doubt that the photographer was gifted with “a velvet hand” and a “hawk’s eye.” His past experience as an amateur hunter equipped him with patience, attentiveness, and precision—skills required to capture the “decisive moment,” the phrase that would become indelibly attached to his work. However, this show, curated by Clément Chéroux, suggests that these qualities were the means to an end, not the photographer’s main achievements and instead strives to convince viewers that there are many faces to Cartier-Bresson.

The exhibition consists of seven thematic, chronologically arranged sections that each reveals a different character: Cartier-Bresson as a potential draughtsman, as a Surrealist, as a communist in his worldview, as an activist, and even as a Zen Buddhist. Three main time periods frame these sections. The first, 1926–35, is mostly marked by early, Surrealist photographs made during his travels; the second, from 1936 to 1946, is distinguished by his return from the U.S.; and the third period begins with the foundation of Magnum Photos, in 1947, and ends in the early 1970s, when he retired from photography and re-embraced drawing. Most of the prints are small and black-and-white, some vintage, and invite the viewer to step in closely to consider the process involved in the making of each photograph; the effect is to dissuade hurried consideration. While Cartier-Bresson’s most noted and loved photographs are on view, they are accompanied by lesser-known images; for instance, those related to his experiences in filmmaking, first as Jean Renoir’s assistant and second director, and later as a documentary-film director during and after WW2.

The exhibition makes clear it was not a coincidence that he was always in what, in retrospect, seemed as to be the right place in the right time. The long-standing focus on his extraordinary ability to capture these moments has implied that it was mainly the fraction of a second that matters. But when looking into Cartier-Bresson’s biography, one can see that he was never a one-night stand photographer. He was never just passing by—in fact, he tended to linger as long as he could. Though he was considered a shy person, it seems that he knew everyone, which enabled him to catch intimate frames of many great people of his time: there’s the photograph from 1961 of Alberto Giaccometti crossing the road in Rue d’Alésia, Paris, while lifting his coat over his head to keep dry from the pouring rain, or the mysterious frame of Jean-Paul Sartre standing with Jean Pouillon on the Pont des Arts on a very foggy day in 1946.

Chéroux’s presentation reveals how he first learned to see the world through the eyes and the philosophy of the Surrealists, whom he encountered in the mid-twenties in Paris. Eugéne Atget and André Breton inspired him to reconsider how he looked at the familiar, and his work from the early thirties shows their influence: dummies and mannequins in shop windows, reflections in vitrines, and expressions of absurdity, irony, and humor. During this time, he also made several series of nude women, some of which might be read today as objectifying but he developed a more respectful approach towards his female subjects in later years.

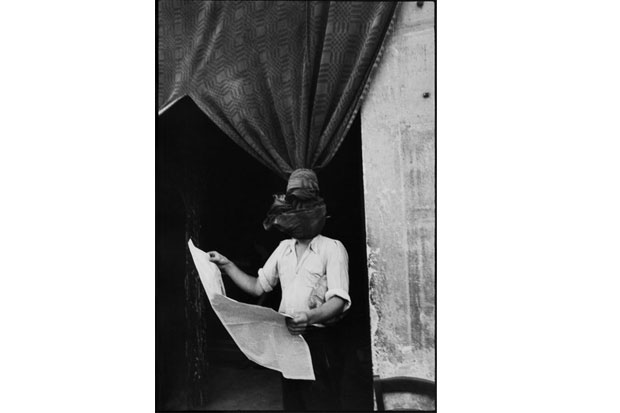

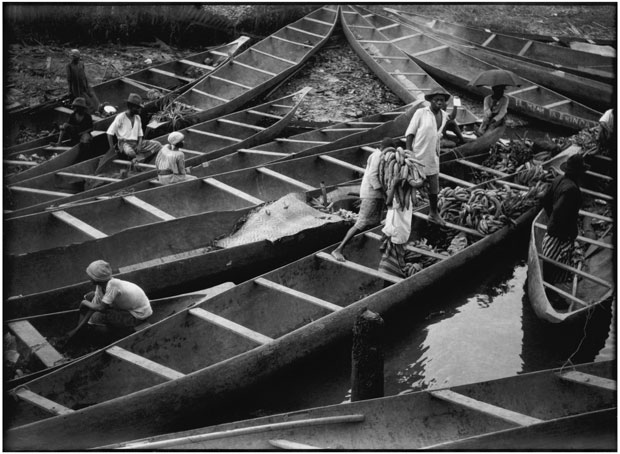

In 1930, he took his first significant trip to Africa. He stayed a year and traveled throughout Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Togo, and along the Niger River toward the colonized territory then called “French Sudan” (today Mali). Well aware of the common representations of the continent through white-European eyes, Cartier-Bresson tried to avoid them, and in the photographs from that trip one can see his attempt to capture mundane aspects of daily life as well as abstract, or more formal representations of people and their communities. Most of the people who appear in these photographs are shot from afar and are organized around actions, movements, and collaborative work, such as loading bananas from small boats on a port or fixing fishing nets as in an image titled Côte d’Ivoire, Africa (Ivory Coast, 1931).

Following that trip, Cartier-Bresson continued to focus on people and their living conditions. In Mexico (1934), a disabled woman is seen walking in a large empty courtyard in a poor neighbourhood in Mexico; she is captured from behind at a respectable, non-invasive distance. When documenting children from poor and neglected parts of the world, such as in Seville, Valencia, or Madrid, in the mid-thirties, and later in the sixties, he also managed to photograph in a way that did not degrade his subjects. Rather than focusing on their harsh living conditions, he captured playful behaviour and peoples’ curiosity about his presence and his camera.

Despite Chéroux’s efforts to broaden our view of Cartier-Bresson’s output and move away from the limitations imposed by the term “decisive moment,” the decision to only focus on the photographer’s activism in the third section of the exhibition, called “Political Commitment,” focusing on Cartier-Bresson’s return from the U.S. and Mexico, is questionable. This is not to say that the works on view do not carry a political tone, but that his work was political before 1934–35. This potentially casts doubt on the photographer’s intentions in other branches of his work; the need to classify by theme runs the risk of generalization, neglecting important nuances. For example, in the second section of the exhibition, “The Attraction of Surrealism,” a large number of photographs are read through the prism of Surrealism, which diminishes their humanistic, social, and political aspects. In one instance, the wall text reads: “the viewer would dearly love to lift the cloth, but the image cannot be unveiled: that is how our desire to see it aroused.” This invocation of the “veiled erotic” seems out of place when applied to photographs such as Livorno, Italy (1933), a picture of poor children who wish to cover their faces in front of Cartier-Bresson’s camera. The same feeling surfaced when looking at another photograph taken in Spanish Morocco in 1933, in which we see a man lying on the ground on a street corner, covered in a dirty piece of cloth. Even with these thematic impositions, the stated curatorial intent to “to trace the history of Cartier-Bresson’s work, independently of the myths and superimposed categorization,” as stated in the exhibition’s catalog, was accomplished, offering fresh ways of thinking about this influential photographer’s work.

—

Henri Cartier-Bresson was on view at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, from February 12 to June 9, 2014. It is now at Fundación Mapfre, Madrid until September 7, 2014. Thereafter, the show will travel to the Museo dell’Ara Pacis, Rome, from September 26, 2014 to June 1, 2015.

Ellie Armon Azoulay is a writer, critic and curator based in Paris. For the past five years she has been an art correspondent for Haaretz newspaper, Israel, and also contributes to other art publications.