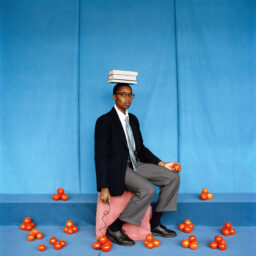

Documenting the Weaponization of Water Along the U.S.-Mexico Border

Richard Misrach, Agua #1, near Calexico, California, 2004; Water placement by the organization Water Station.

© the artist

Last month, four volunteers for the Arizona-based humanitarian aid group No More Deaths were convicted on misdemeanor counts of trespassing after entering the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge without a permit in 2017. Charged with threatening “pristine nature” (in the words of U.S. Magistrate Judge Bernardo Velasco), they left canned food and jugs of water in an uncompromising expanse of protected desert in order to help long-journeying migrants suffering from dehydration and malnourishment.

The volunteers knew the statistics of the pristine desert all too well. Since 1999, more than three thousand migrant deaths have been reported to the Pima County medical examiner, but as so many have pointed out, those numbers are necessarily low. Bodies decompose fast in the desert sun. The story of migrant death along the U.S.-Mexico borderlands always carries an even grimmer footnote: there are many more. The deserts of Arizona and California are many things to many people, and they are also certainly graveyards, landscapes now defined by human remains scattered amidst saguaro cacti and lowland brush, disintegrating into dust in heat-stunned canyons and gulches.

The Border Patrol has never liked the work of No More Deaths or their California counterpart, Water Station, which for years has installed large blue barrels full of six-gallon water jugs in remote stretches of terrain. Agents have been known to shoot up barrels, slice open and empty jugs, and destroy canned food.

Richard Misrach, Bullet-ridden water station, Carrizo Creek Gorge, California, 2014

© the artist

When Richard Misrach traveled the California and Arizona deserts in 2014, taking photographs that would find their way into Border Cantos, he worked closely with both organizations. He hiked with No More Deaths volunteers in Arizona, photographing them near Arivaca on a trek to deposit water jugs. In his Agua series, he shot over four dozen images of water station barrels and beacon flags, including one barrel dripping red paint into bullet holes left by the Border Patrol. Installed next to a fallen shade tree in the Carrizo Gorge, the water station is only feet from a cross of white stones, a makeshift migrant grave.

Richard Misrach, Water placement by the organization No More Deaths, near Arivaca, Arizona, 2014

© the artist

As part of his Border Cantos collaboration with Misrach, composer Guillermo Galindo turned these visual traces of volunteer aid and the attempts to stop them into musical instruments and sonic outcries. In his Water Station Scores, Galindo superimposed forensic data of human remains over Misrach’s water station photographs. In his Sarape Tracking Flag, he printed a musical score on a tattered water station beacon. But his crowning intervention is Fuente de Lagrimas (Fountain of tears), a blue water station barrel that slowly drips water onto a slab of rusting metal floor. When the drops hit, you can hear the weaponization of water in the age of militarized border enforcement. Galindo compares it to “rain falling onto a tin roof,” but this is no symphony of shelter. This is a grueling drip-drop rhythm for a place where shelter is scarce, help has become a criminal act, and no Samaritan is safe.

Click here to purchase Border Cantos at a discount. For the duration of the sale, Richard Misrach and Guillermo Galindo will donate 100% of their royalties to the Arizona humanitarian group No More Deaths.