William Christenberry, Poet of the Ordinary (1936–2016)

Aperture remembers the life of the Southern photographer, whose work evokes the power of passing time.

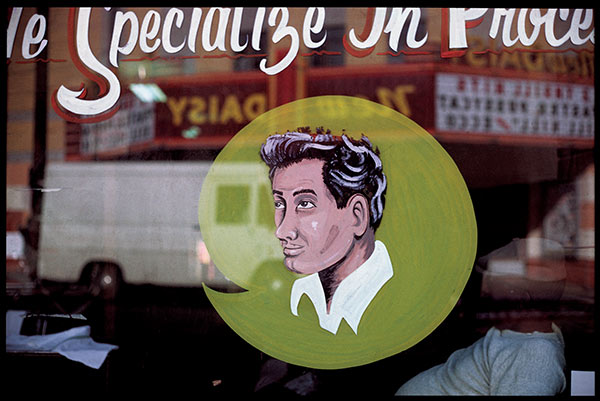

William Christenberry, Processing, Beale Street, Memphis, Tennessee, 1966

In 1963, as director of the Pasadena Art Museum in California, I mounted a retrospective of the work of Marcel Duchamp, which was widely reviewed. I had put together a catalog and a poster for the show, and I was very proud of both of them, but we sold precious few, and almost none by mail order. One day, my secretary was going through the mail, and she said, “Here’s a strange one. Somebody in Memphis, Tennessee, has written requesting a catalog, and he’s sent fifteen dollars.” I said, “Who the hell in Memphis, Tennessee, would want a Duchamp catalog?” Duchamp, at the time, was not exactly a household name in the South. Because the catalog cost less than fifteen dollars, I told my secretary to throw in a poster as well.

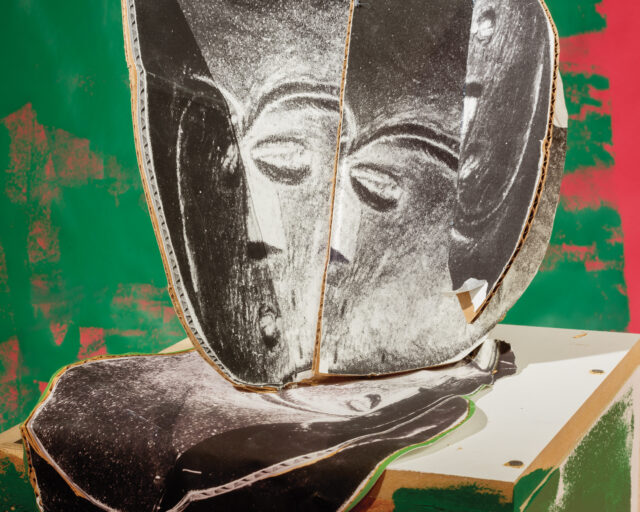

William Christenberry, Signs in Landscape, near Marion, Alabama, 1975

Years later, I was in the atrium of the Corcoran Gallery in Washington one day when a lanky-looking man came up to me and said, “Excuse me. You’re Walter Hopps, aren’t you? I just wanted to thank you for that Duchamp poster you sent me.” He told me his name and explained that he was living in Washington now. I asked him what he did, and he said, “A little bit of everything. I draw. I make sculpture. I’ve done paintings. I take photographs.” In an age when everyone else looked like a hippie, he was short-haired and straitlaced and very polite in a southern way. I asked him if I could come by sometime and see his work. When I got to his house, I looked at everything he’d been doing, but the minute I saw the photographs—both black and white and some small ones in color—a light went on in my head, and I knew that they were special. As Walker Evans once said, they were like perfect little poems. I often wondered afterward whether I ever would have met Christenberry if I hadn’t sent him that Duchamp material. He was shy—it might have taken years.

William Christenberry, Double Cola Sign, Beale Street, Memphis, Tennessee, 1966

William Christenberry was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, in 1936, and spent a lot of his childhood in Hale County. He went to the University of Alabama at a time when many of the teachers there were former students on the GI Bill. One of those teachers turned out to be important in his life, a graduate of the California School of Fine Art named Lawrence Calcagno. Calcagno turned out not to be one of the majors himself, but he was a sophisticated, mature person, and he opened up all kinds of things for Christenberry. He sent him to the library and forced him to look at art he’d never heard of before. A couple of years after college, Christenberry moved up to New York to look for work. He got a job at Bella Fishko’s gallery. That didn’t work out. Then he got a job cleaning Norman Vincent Peale’s church. That was too depressing. Next he was taken on as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art. That was too boring. Finally, he heard that Walker Evans was working at Time-Life and Fortune magazine. This was late in Evans’s life, and he had been almost forgotten. Christenberry went over to the Time-Life Building and met with him. Evans, who never had a son, took to Christenberry right away—especially when he realized that his family lived right down the road from the people he’d photographed for his book with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Evans had documented the lives of sharecroppers in the area; Christenberry’s family was just one rung up the ladder—they owned the land they worked on. So that was a real connection between Christenberry and Evans, and it was Evans who encouraged Christenberry to go back to the South for his work.

William Christenberry, Building with Nehi Sign, Stewart, Alabama, 1965

Agee, in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, called for the use of the most humble materials to create a lyric poetry of everyday experience. Words “are the most inevitably inaccurate of all mediums of record and communication,” he said. “Words cannot embody; they can only describe.” To convey the dignity of the lives observed, one must form a montage of details—scraps of iron, the wood from a table, a broken chair, chickens. This is the aesthetic principle that Christenberry has been developing since the 1950s, and he has done so in an extraordinarily wide variety of media. He has also devoted considerable attention to one particular fringe element of the American South: the Ku Klux Klan. Curator Thomas Southall has written of Christenberry’s Klan pieces, “This creation, like his other work, has a way of giving physical form to intangible feeling. We are left not with a simple polemic or documentary statement, but with a new sense of how complex and deeply rooted prejudice is.” For Christenberry, these fetishistic works seem to constitute a kind of exorcism of racism.

William Christenberry, Child’s Grave with Pink Rosebuds, Hale County, Alabama, 1975

What fascinated Christenberry about Duchamp was that Duchamp could make art out of anything. He was, to use the French word, a bricoleur—a fix-it man, an improviser of modest and humble materials, who can patch your chair or fix your chicken coop. In Christenberry’s work, Duchamp’s and Agee’s ideals come together: even the most modest of farmers knows inherently how to survive. If the plow breaks, he knows how to mend it. If he can’t find tar paper for his roof, he figures out how to insulate with newspapers. His life is an improvisation. When Christenberry saw all the found materials in Duchamp’s work—the old bottle racks, the bicycle wheels—he felt an instinctive rapport. It makes Christenberry nervous to call what he does art. For him to take a good picture is simply a matter of getting the right kind of crop planted and then harvesting it on time.

What a harvest.

This essay was originally published by Aperture in William Christenberry (2006).