A Portrait of the Socialites as Bright Young Things

Everything was so beautiful, until it wasn’t. The parties, the costumes, the faces, the promises.

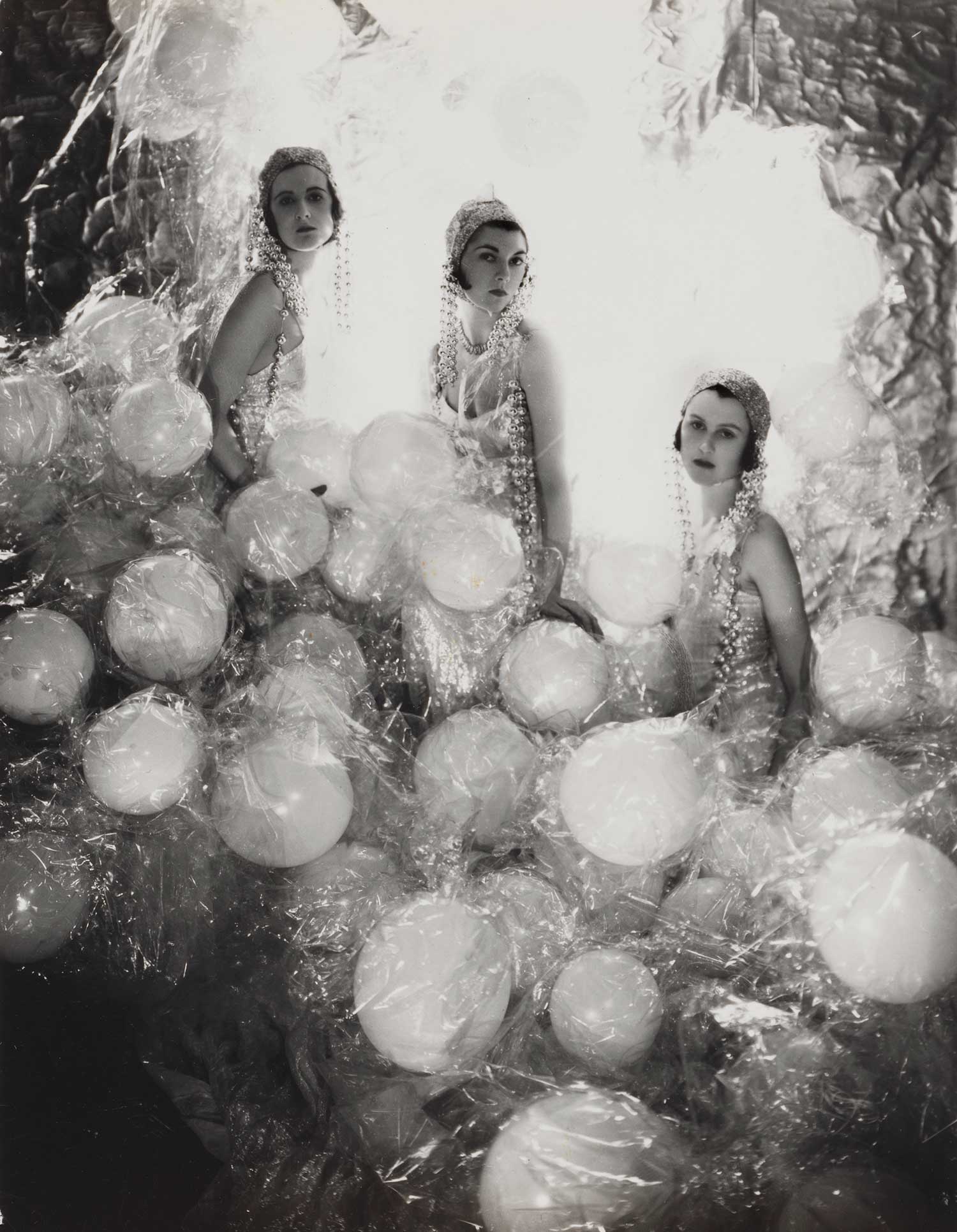

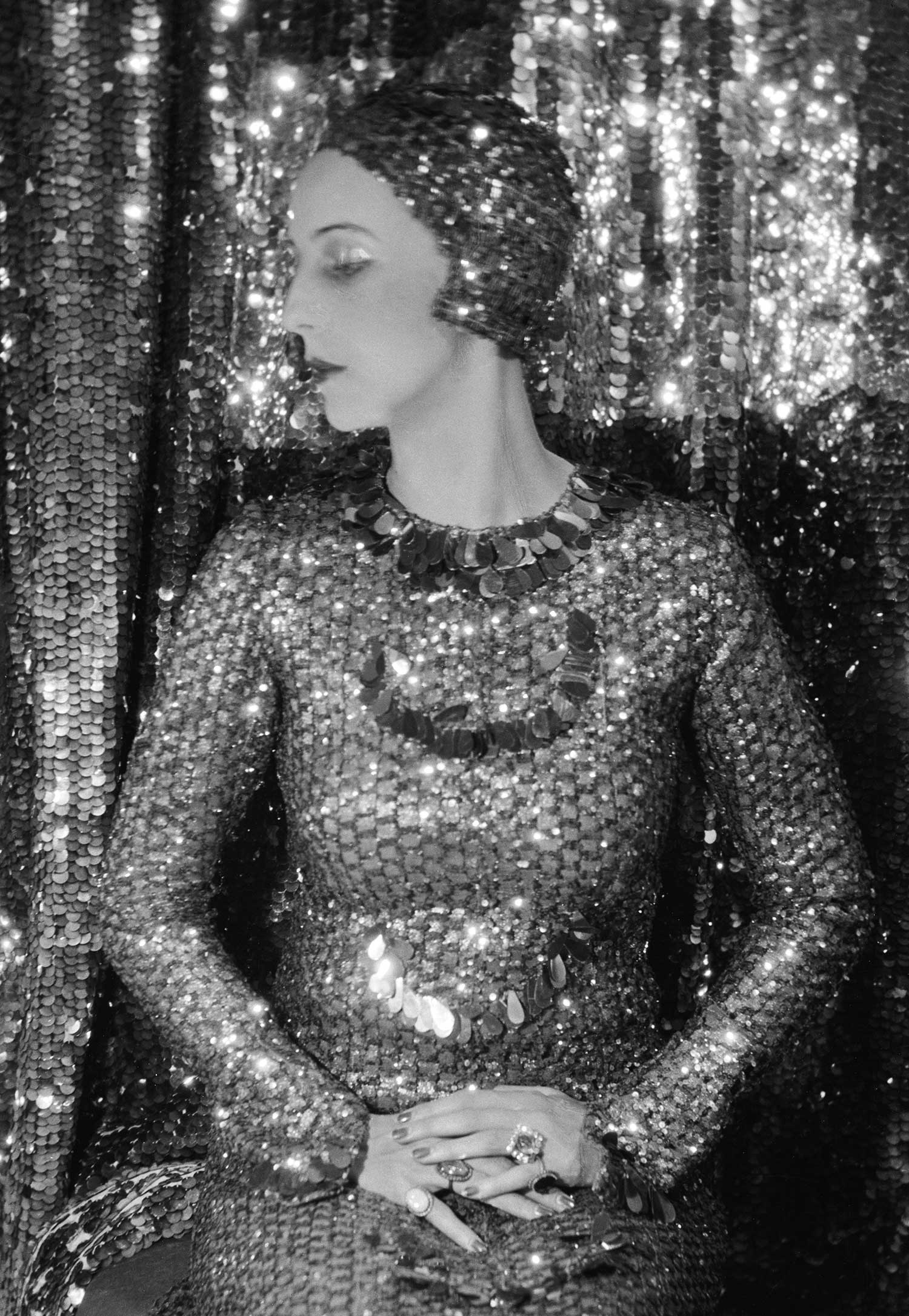

A visit to the exhibition Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things at London’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG)—before it was closed due to the health crisis—or a read of the accompanying catalogue, provokes a complex kind of tenderness. It’s an imagined nostalgia for the seemingly carefree nature of the interwar years, when the parties were long and the people were unashamedly flamboyant; the days when an elaborate headdress, or the gushing words of so-and-so, could be a ticket to social and artistic success. But there’s an odd kind of revulsion too—at the excess, the navel-gazing, the bickering, the frivolity, the wastefulness, and, of course, the emptiness beneath the glitter.

Yes, Bright Young Things is a diverting riot of stylized portraits, silver hues, polka dots, doodles, and Beaton-style handwritten headings, a festival of high-society titbits and deliciously witty hearsay, located by the exhibition’s curator, the talented Robin Muir, in various biographies and diaries. Even the tone of Beaton’s diary-writing seems to have seeped into Muir’s text, which talks gayly of great beauties, meteoric success, effortless humor, and all manner of people coming up and down to Oxford and Cambridge.

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

But there’s a probing sense of concern too. In the catalogue’s introduction, Muir writes of the summer of 1927, which solidified the reputation of the Bright Young Things, the monied young people who delighted in endless parties and dress-up opportunities. He quotes from the diary of Evelyn Waugh, who bullied Beaton at school, and whose novels—especially Decline and Fall (1928) and Vile Bodies (1930)—are deliciously bitchy takedowns of the whole Bright Young Things scene. “I went to another party the other night,” wrote Waugh. “Everyone was dressed up and for the most part looking rather ridiculous. Olivia had had her hair died and curled and was dressed to look like Brenda Dean Paul. She seemed so unhappy.”

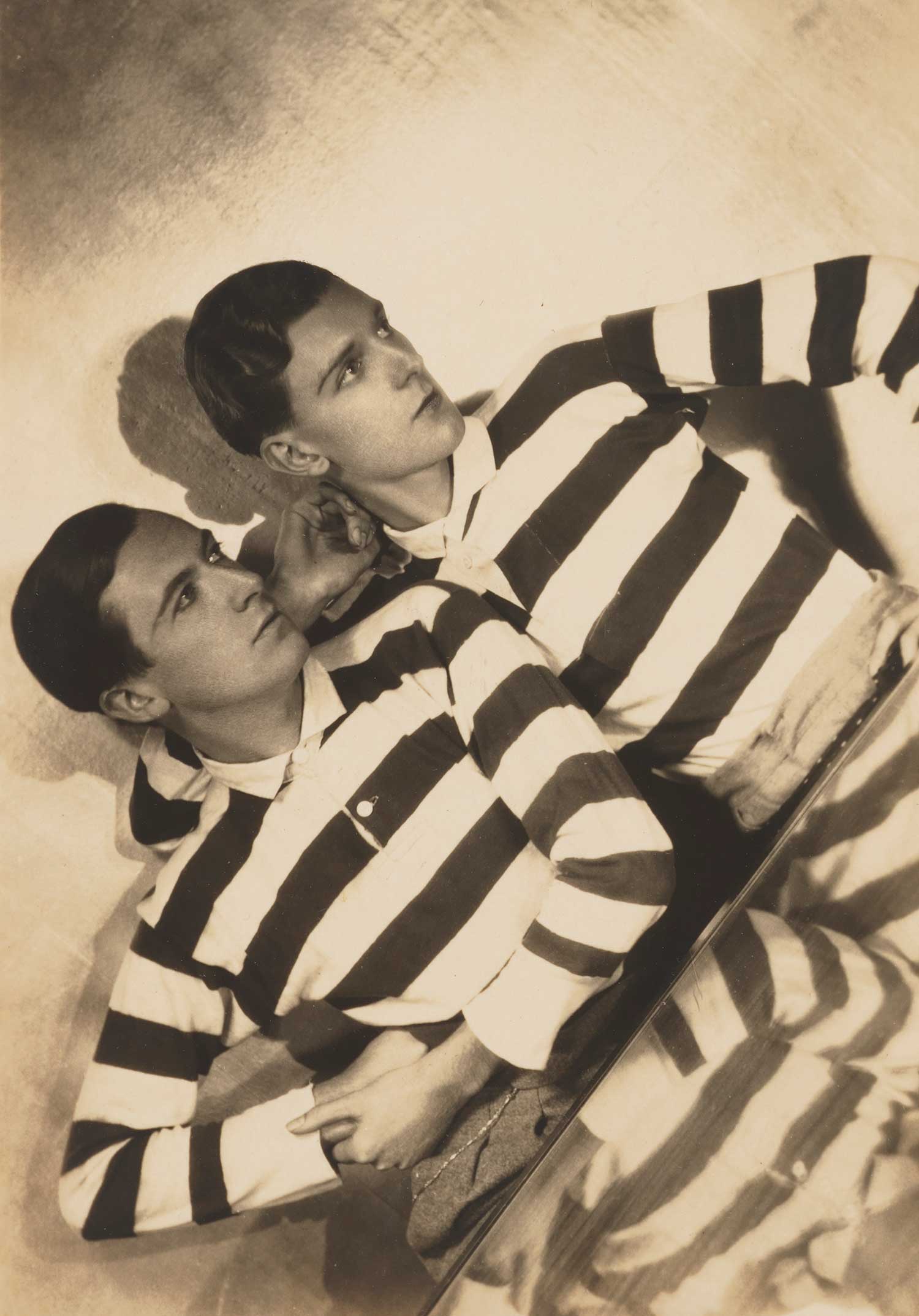

Dualities are a good way of thinking about Beaton’s work, which is, in some ways, in step with the zeitgeist, when one considers his devotion to artificiality: the performance of identity, a freewheeling approach to gender, the idea that through dress and image, you can become the person you want to be and transcend your lot. Yet these same qualities might strike as jarring, given the conversations around privilege and representation abundant in photography—and society—today. Beaton’s folk were posh folk; the book itself is largely a who’s who, ordered by name and family—the Sitwells, Stephen Tennant, Lady Diana Cooper, the Countess of Oxford and Asquith, the Princesse de Faucigny-Lucinge, the Marquesa de Casa Maury, the Maharani of Cooch Behar.

There is talent amongst it all. A web of names spins around every image, every interaction—Virginia Woolf, the actress Anna May Wong, the economist John Maynard Keynes, the author Daphne du Maurier. Everyone seemed to know everyone. And they are all lovely looking, and maybe that in itself is just fine. Beaton, after all, didn’t pretend to care about much more than appearance (recall the title of his lauded book, The Book of Beauty, from 1930, which featured drawings and photographs of some fifty sitters, personally selected by Beaton as a means of cementing his status as an authority on taste, fashion, and the general hierarchy of who was in and who was out). Beaton’s goals, read aloud by Muir at the exhibition’s opening back in March, were, “all the trappings of celebrity.” In 1923, Beaton wrote, “I don’t want people to know me as I really am, but as I am trying and pretending to be.” Has there ever been a more modern sentiment, so fitting for the Instagram age?

As Nicholas Cullinan, the director of the NPG, explains in the catalogue, Beaton’s work offers a nice narrative arc when it comes to the museum’s—and, indeed, Britain’s—display of photography. This is the third Beaton exhibition at the venue. A large retrospective in 1968 was the first of any living photographer to be held in a British museum. The exhibition was extended twice, and its installation saw the gallery change its stance of displaying portraits of living sitters; after the show’s success, the gallery hired its first keeper of photography and film. Another display of Beaton’s portraits was mounted in 2004. It seems fitting that Bright Young Things comes at a time of transition for the gallery, which is scheduled to be closing this year for renovation, and at a point when questions around photography, and, in turn, gender, performance, style, and identity (all Beaton themes) are in a dynamic period of flux.

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

Those interested in detail will be well served. Muir, with meticulous research, encourages us to think about the amount Beaton did with so little. At the start, Beaton’s tools were little more than his patient sisters, a folding Kodak A3, and a stash of bedsheets and household objects to be used as backdrops and props. Muir describes Beaton’s photographic style, once fully developed, as “a marriage of Edwardian stage portraiture to nascent European surrealism, filtered through a determinedly English sensibility, one that revered in particular the modes and gestures of the upper classes.” The pictures themselves reveal something elemental about the human condition, about wants, needs, social habits, manners, norms and, that all-important factor in Beaton’s career—maybe the most important factor of all—ambition. We see, through Beaton, his subjects’ relentless search for distraction and, simultaneously, for meaning. We see their quest for a semblance of place, a home, but also, in contradiction, for freedom—for an escape from the humdrum, for that heady, if sometimes startling, sensation of not being trapped, never fully attached, maybe never fully present.

Still, of course, it had to end somewhere. And Bright Young Things smartly chronicles the demise, as well as the rise, of the Bright Young Things—including Beaton’s own fall from grace after he submitted a design with an anti-Semitic slur in the margins to Vogue in 1938. Clearly, from the very fact of this book and exhibition’s existence, and the countless more before it, the downfall was short lived.

© Estate of Paul Tanqueray and courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

Elsewhere, we learn of the addictions, the suicides, the time wasted, the unfulfilled potential. I found myself moved by the restlessness of it all—the hedonism, the vaguely nihilistic sense of freedom, but also the guilt. The Bright Young Things were the generation after the war had passed. They were, for a while, the lucky ones. There was, like today, a remarkable split between generations, a chasm between young and old. And if you were young, you were so very young.

Post-lockdown, post-COVID-19, post–all the death and anxiety and the relentlessness of being cooped up and afraid, will the young of today fully take up their place as a “generation after”? Will it be the roaring twenties all over again? Will they break free from worry into parties and make-believe and lightness? Or will they do something more? I’m sure the latter, but who can know. The words of Lord Metroland, in Waugh’s Vile Bodies, have never seemed more poignant: “There was a whole civilization to be saved and remade. And all they seem to do is play the fool.”

Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things opened at the National Portrait Gallery, London, on March 12; the museum is currently closed due to the coronavirus crisis. See the museum’s website for updates.