Xmas tree, December 28, 1975

Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

Prison changes everything. This is what people who have done time understand. On July 2, 2020, my friend Rojai Fentress was released following a conditional pardon by Virginia’s Governor Ralph Northam. Rojai had served twenty-four years of a fifty-three-year sentence, after being convicted at sixteen by a jury of his peers of a murder that he didn’t commit. The day he was released, he told me that he had never been higher than the second tier, prison nomenclature for the series of cells on the second level of the large warehouse-like spaces that are called “housing units.” He said that in the forty years he had been alive, there had never been occasion for him to be more than fifteen feet in the air. Fats, which is what everyone who has done time with Rojai calls him, was describing the particular kind of violence that the circumstances of confinement brought to his life—a denial of what’s possible, even something as simple as looking out over the edge of a mountain.

Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

And yet I know that even within the confines of those small and cramped spaces, he found many opportunities to be free. On the basketball courts, doing pull-ups on the backs of iron stairs, developing an eye for drawing portraits, sharing a complicated meal built around fifteen-cent ramen noodles and cheese crackers. This interior life of men in prison is what is too often hidden, and this is part of what Nigel Poor has given men an opportunity to reveal through her work. When I spoke with Poor about her new book The San Quentin Project, in which men in prison reflect on and demonstrate the richness of their inner lives, she said the book started while she was teaching a class in the Prison University Project (which was an extension of Patten University and is now called Mount Tamalpais College). For Poor, and the men involved, the class was about working with “photographs as a bridge for conversations about their personal histories.”

Courtesy Aperture; Photograph in work © Stephen Shore, courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery, New York

But to fully grasp the interiority that prisoners seek to assert, it’s important to understand what they are asserting it against, particularly Black and Brown prisoners. In “Strivings of the Negro People,” an 1897 article in the Atlantic, W. E. B. Du Bois recognized that he was shut out from the world of others around him by “a vast veil.” The point is that between the world and Black folks, there seems to be something that forces them, us, to have a kind of double vision. Or as Du Bois framed it, a double consciousness, a “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” Prison offers a different, related but more conflicted kind of double consciousness. As philosopher and prisoner James Davis III explains, those in prison have a double- double consciousness. He argues that the Black prisoner enters his confinement with the double consciousness described by Du Bois and then, is burdened by the double consciousness that incarceration imposes—that “concrete veil that obscures his humanity . . . the lack of recognition [as a human] that threatens to alienate him from the inalienable rights with which he was born.” The prisoner understands that, after having been to prison, nothing is ever the same, and so much of the work of living (both inside prison and outside) becomes about remembering and asserting that you can have agency and a life, without either forgetting or being consumed by your memories. Put another way, you walk, handcuffed and shackled, into a prison and become someone that you hadn’t been before.

![W. H. Woodside, CO [Correctional Officer] fight, April 8, 1961<br>Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison”>

</div>

<div class=](https://aperture.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NP_018_Archive-HR-scaled.jpg)

Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

As a child, I read several memoirs about prison, including Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land (1965), Nathan McCall’s Makes Me Wanna Holler (1994), and a book I had randomly found at the house of an aunt, Albert Race Sample’s Racehoss: Big Emma’s Boy (1984). But these books didn’t prepare me. The philosopher L. A. Paul writes in her book Transformative Experience (2014) about events that substantially revise “how you experience being yourself.” Paul defines an experience as epistemically transformative when the only way to know what the experience is like is to have it yourself. This is why there was no way that Brown, Malcolm X, McCall, Sample, or any of the countless other authors who have written of prison—or even the films that depict life there—can make you know the experience of incarceration. Maybe the point is that these books ultimately aren’t about making you know prison, but rather providing a glimpse of what cannot be understood.

I’ve known the expansiveness and the deep solitude that prisons create. The frustration, the fear. But also the gifts: laughter, grit, possibility. The dilemma of the writer narrating the prison experience is that despite their best efforts, there is always something about incarceration that cannot be fully conveyed. And given this, there is a need for metaphor. The notion that a picture is worth a thousand words is suddenly true when I remember the contraption a man built with wires and a pair of nail clippers to heat water. Prison gives the people who have done time a new way of seeing, a different way to understand the world, which is both a gift and a curse. The San Quentin Project reveals something of that double vision, that sight and insight.

Courtesy Aperture and San Quentin State Prison

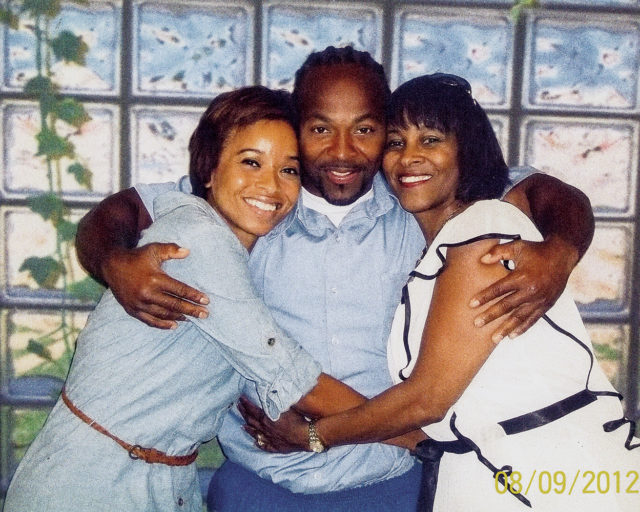

What this book establishes, first, is that incarceration does not dim the desire to be full. These photographs—probably taken by correctional officers in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, while some may have been taken by men who were incarcerated at the time—tell a different story of prison. By bringing these photographs to the world, Poor makes an argument for the capaciousness of both the lives that incarcerated men experience and the loss that ripples through their days. One image, Mother’s Day, May 9, 1976, depicts a family reconnecting while visiting San Quentin. Everyone has on a version of their Sunday best, and it is impossible to tell who, if any of them, is incarcerated. In another photo, a group of men pose behind a drum set, with one cat leaning on a guitar that reminds me of the one Prince threw into the sky as he walked offstage after a performance. The image of a Native American, in full regalia in a prison yard, is arresting and makes us pause. What men do to avoid the erasure of prison is as unpredictable as it is vital. Images of men together on a football field, in uniforms and helmets, men lifting weights, even a man whose eye is stitched and swollen closed, are reminders of what the living do. It is only when you see the bars, the narrow corridors of violence, when the angle of the image brings to mind Michel Foucault’s criticisms of the panopticon—where prisoners are controlled by constant observation—that the constraints of prison become part of the point. What is left out of the images reminds us of how much of life in prison remains undocumented.

© George Mesro Coles-El, courtesy Aperture; Archival image courtesy San Quentin State Prison

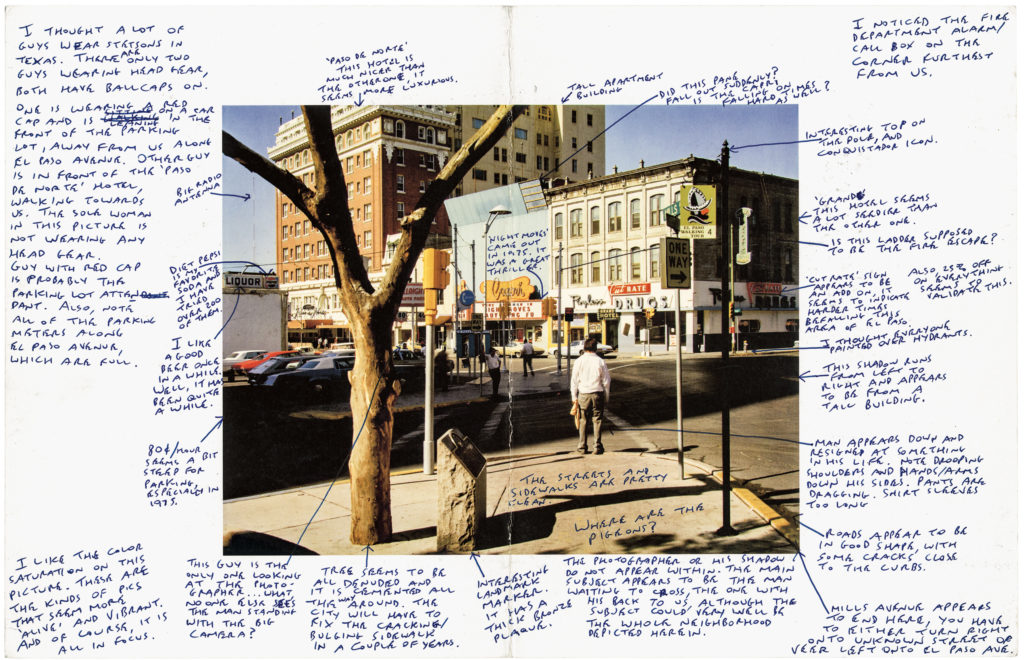

Most poignantly, this project allows men inside to begin contemplating—through their stories, annotations, and conversations—the moments that the photographs leave out. The students in Poor’s class not only reflect on their lives or on lives adjacent to theirs but also provide insight into the iconic works of well-known photographers. How do you begin to interpret moments you haven’t begun to live? The San Quentin Project gives us a chance to witness this process of close reading. “That distinct voice,” as Poor says of the guys inside, “is really beautifully communicated to somebody who doesn’t necessarily have the experience.” These voices and these stories create a space of compassion for us all to rest in. And yet, Poor’s project is far more significant than just bringing images that haven’t been seen before to the public. By allowing men on the inside to annotate photographs, she forces readers to become witnesses to how deprivation changes how we see. And the stories, frequently, become a meditation on loss. A man describes a stabbed body as a “once proud castle.” The point becomes a revelation, not just of the stories that this particular photograph might contain but of all the stories that have been buried by prison.

This essay and images were originally published in The San Quentin Project (Aperture, 2021).

A portion of the sales from The San Quentin Project are being donated to Mount Tamalpais College at San Quentin State Prison. This publication is also part of the Million Book Project, which will create curated libraries of five hundred books to be distributed to one thousand prisons and juvenile detention centers in the United States.