Carrie Schneider, Madame Psychosis (Joelle van Dyne) (detail), 2023

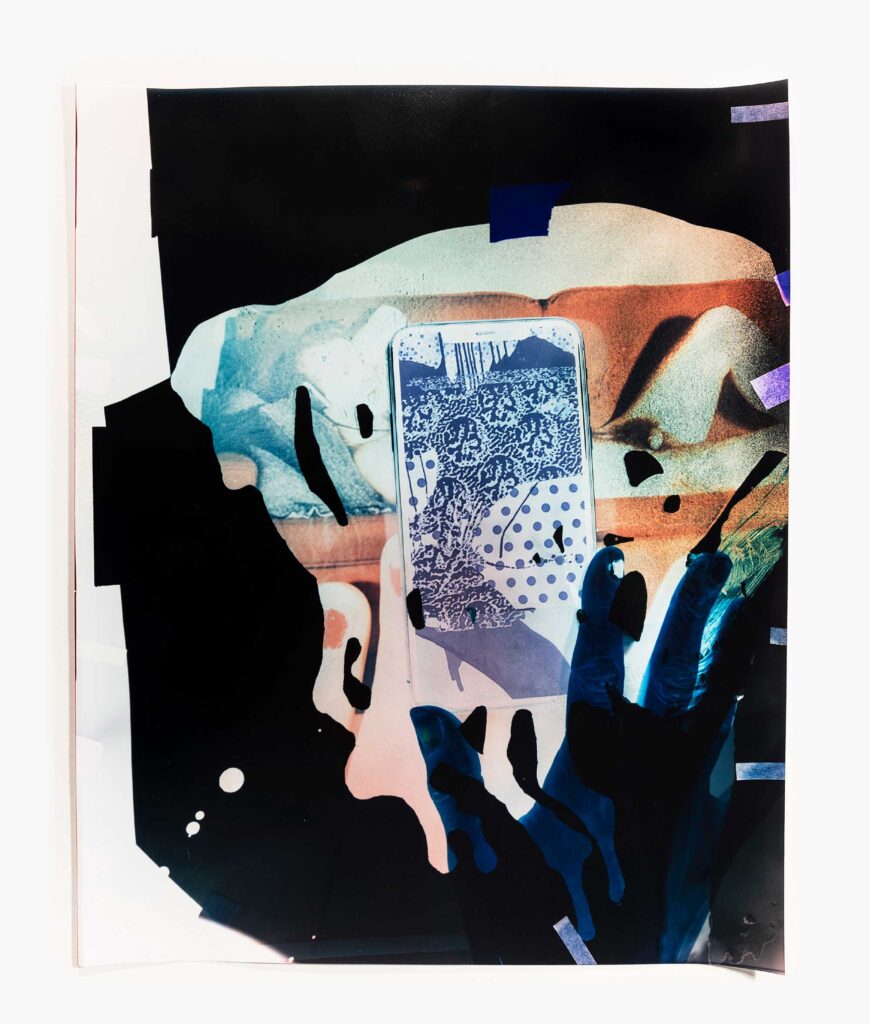

In the vast former-factory space of MASS MoCA, a singular, inscrutable, sculptural photograph, titled Madame Psychosis (Joelle van Dyne) (2023) and measuring an astonishing forty inches by eight hundred feet, unfurled in a seemingly endless scroll, pitched in a roof formation at its peak and rippling out over a large plinth. Another work (Infinite Kill, 2023) cascaded across the gallery’s walls. In the adjacent spaces, one room displayed more than a hundred dreamlike, abstract photographs—multiple exposures of images sourced from a litany of artists, films, and social-media feeds of the artist’s friends, layered onto personal images. Lurid with color, all were photographed and rephotographed in dark, transitory, predawn hours. Here, they were installed with little wall space separating each of them, emphasizing their shared connection. And projected in the back room is a 16mm film that exudes a Warholian Screen Tests energy. Composed of stills showing the actor Romy Schneider, the work flickers on the walls so that Romy seems to watch her own image scatter around.

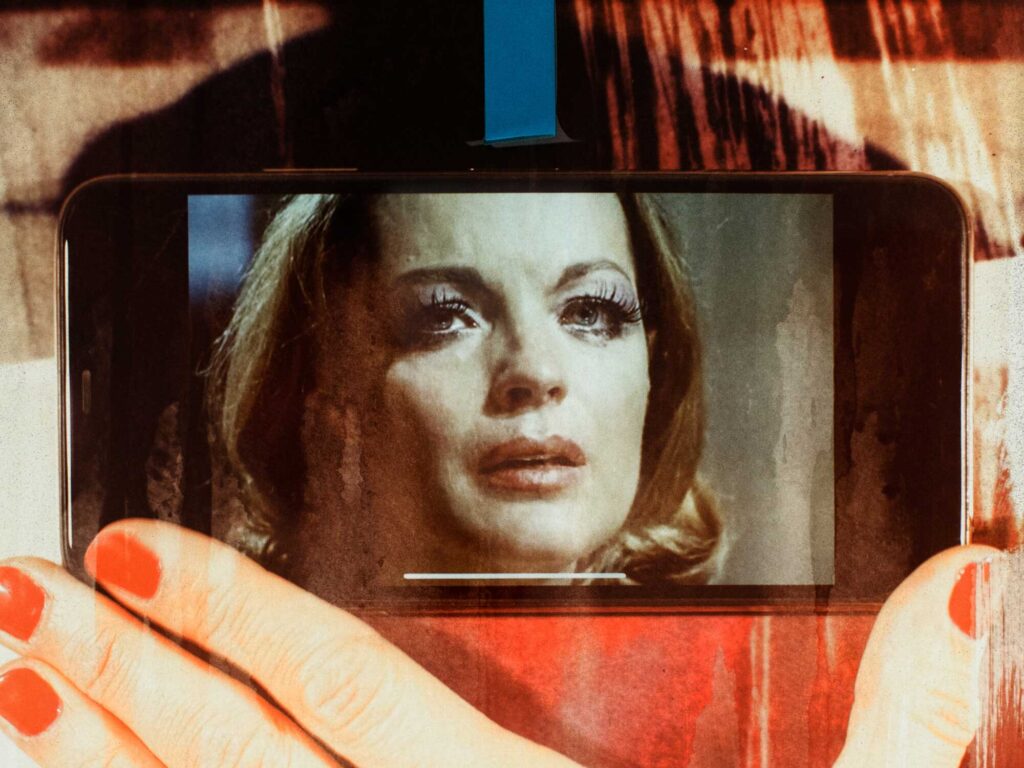

The film is Carrie Schneider’s Sphinx (the answer isn’t man) (2023). Sphinx is also the title of her solo exhibition at MASS MoCA, curated by Susan Cross, which was on view from March to September 2023, and featured work that the Brooklyn and Hudson, New York–based artist made beginning in the fall of 2020. All Schneider’s vivid, sometimes gigantically large photographs were made with a room-size camera that she built herself out of industrial plastic and outfitted with a Rodenstock lens. (Some of the pieces have been shown at Candice Madey and Chart galleries in New York.) As in previous series that incorporate self-portraiture, personal traces of and references to the artist were present in Sphinx too. There’s Romy Schneider, who shares the artist’s surname, in the film, and in Infinite Kill, where she appears on a phone screen that the artist cradles in one hand, nails painted bright red, and holds up to the camera. Revenge Body (2022), a floor-to-ceiling photograph of a repeated abstracted still from the 1976 film Carrie, depicts Sissy Spacek’s title character, who shares the artist’s first name, her face dripping with blood.

On the surface, the pieces that made up Sphinx represent a radical and monumental shift in scale, material, and conception within Schneider’s practice, but also in thinking about photography itself. This is work that particularly invites and rewards close looking, revealing subtle and surprising connections with many of Schneider’s previous series of photographs and videos, from Burning House (2012–13)—for which she built to scale a small house on a tiny island, set it aflame, and filmed its burning—to her numerous collaborations, including those with the choreographer and dancer Kyle Abraham, artist Abigail DeVille, and composer and musician Cecilia Lopez.

I first met Schneider in 2009, when we were both in residence (in visual arts and fiction, respectively) at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, where Rineke Dijkstra was a visiting master artist. A few years later, I participated in Reading Women (2012–14), comprising immersive photographic and video portraits of a hundred of her women-identifying friends and peers reading books by other women in their homes or studios. There’s a clear path, it seems to me, from Reading Women to Sphinx. As artist and filmmaker Cauleen Smith (who also participated in the former project) wrote in a 2014 essay titled “Carrie Schneider’s Grown-Ass Women: You Better Recognize”: “She sits with her. She lets her be. Like a thermal current on a cool day the condensation of a woman into a being of pure thought, silent and in violent motion at the atomic level offers mad quotients of marvel. A woman reading is not accessible or controllable. We cannot know what she might do. We are left to wonder.”

Unraveling and unfurling their inner selves, reclaiming how they are seen, the works in Schneider’s Sphinx similarly unspool their riddles before us. Recently, Schneider and I spoke about the process of making Sphinx and discussed its influences, ranging from Imogen Cunningham to renowned film theorist Laura Mulvey, author of the landmark essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” and creator of films including Riddles of the Sphinx (1977).

Rebecca Bengal: Congratulations again on such a brilliant exhibition and catalog—which has stayed so much on my mind since I got to visit earlier this summer. I’m curious how the exhibition changed for you during the span of its run.

Carrie Schneider: Thank you! It was so fresh when I installed the work. My studio is a renovated one-car garage, so there was no way for me to test out these large sculptures. I had been making them in this camera that I built, exposing hundreds and hundreds of feet of this color chromogenic paper—there’s something like 4,600 feet of paper in all in the show—but until we installed, they existed as a plan in my mind of what I wanted to make.

I installed for two weeks straight with a crew of twelve people, and it really extended the way that I thought about the work immediately. It just exploded my brain. I felt like suddenly I had twenty-four arms, and it also really made me think of the next six projects I’ll make. I’m still unpacking what it was like for me to finally see it in this space: I feel like, when it opened, it was so new on the walls, that I really saw it as other people saw it. I’m still in a state of semi-confusion. It still feels very new to me, even though the show itself is almost over.

Bengal: It’s true, even some of the first works in the exhibition feel so new in this context. I’m thinking of Deep Like (2020–21), your series of 105 pictures, all around twenty by twenty-five inches, which take up an entire room in the show. How did that work lead to the larger pieces?

Schneider: Those were the earliest kind of experiments. I think of them as being my alphabet for the language that I then develop in the larger works in the adjacent galleries. I was exposing this chromogenic paper through the lens of this camera that I built in my studio in the pandemic, and then I decided I wanted to scale up. So I made larger prints, I built my camera a little bit larger, just further exhausting the motifs. And then I really leaned into using an image that started in Deep Like: really looking at the face of the actress Romy Schneider.

There was a certain moment where I realized that didn’t need to cut the paper. It was coming in these long rolls, shipped to my home during the early pandemic. And instead of cutting the paper in the dark and putting it into my camera, it just dawned on me: I’ll just continue to advance the paper kind of frame by frame or bit by bit, exposing a continuous roll. That was, maybe about a year into making the work, when I had that realization that I wanted to just use the material in this way that was really structural, expanded into hundreds of feet-long photographs. And then I had to figure out how I would show them, how they would become installations or sculptures, kind of coming off the wall.

Bengal: When and why did you decide to build your own camera?

Schneider: Before the pandemic I’d also been doing a side project where I was figuring out how to expose chromogenic paper through the camera’s lens, and filter it so that if I were to reshoot it as a paper negative, it would faithfully invert—achieving a kind of black-and-white and a neutral tone. And I had been making tests for years using a large-format Deardorff camera that I bought from a mentor.

I was ready for it to move to the next level. I really knew I wanted to scale up, and I’d been shopping around how to get a custom camera built. But the quotes I was getting felt prohibitively expensive, and of course it’s the pandemic, and everything was so demoralizing. One day I’m out on a run and I thought, suddenly, Oh my god, I know how to make a fucking camera! It’s just a light-tight box. It’s just a dark box. It doesn’t have to be beautiful. And that same day, I went to Home Depot with a mask on and bought all that stuff . . . I think it was something like $110 total. And I went home and I made it, and it completely worked, first try. What I’m working with now is maybe the sixth generation of it. It’s slightly bigger now. I call it my Frankencamera.

Bengal: It makes me think about the sculptural aspect of your work, especially projects like Burning House: the idea of a camera as a house.

Schneider: Exactly. They’re actually about the same size. And of course, camera means “room” in Latin.

Bengal: Your approach to this work is so intuitive and original, but I also know there’s some important inspirations for you lurking in its backstory.

Schneider: I really love everything about Imogen Cunningham’s work, but there are these two negative images in particular: one is of a snake, and one is of her friend Roberta. When I first saw that one, Roberta (Negative) (1961), about fifteen years ago, I thought, What is this? I immediately printed it out and put it on my studio wall. I think what she did is she just used a paper negative, kind of like a contact sheet in reverse. I just wanted more things like that to exist in the world.

Bengal: It’s such a cool and incredible picture. What else about it, specifically, drew you in?

Schneider: What I took from it as a kind of a stepping-off point is seeing how an image of a familiar thing in negative produces this really uncanny effect. I think the image of Roberta is just some textures, like plants and her face. It’s just that simple, but when they’re inverted and negative and kind of superimposed on one another, the results are so surprising. So what I took from that is that the magic didn’t really need to be made with much, but to just be open to experimenting with everyday things floating around. I didn’t feel like I had to go too far to find something that might produce something satisfying to me in a similar way.

I don’t know if I’ve made my Roberta (Negative) yet, but I feel it gave me permission to start really simply, just shooting from within a dark room out of a window. Just seeing how the world outside looked in negative. I think it was very, very simple at first, and then pretty soon after that I started getting a little more weird.

Bengal: With Deep Like, you sourced images from friends’ and others’ social-media feeds, starting when we were all a bit isolated in early pandemic days. Were you actively looking for images at first, or was it born out of mindlessly doomscrolling in that doomy era?

Schneider: I don’t think it was so conscious at first. When I’m teaching, I try to remind my students that it’s okay to work intuitively because you have this whole armature of theory, or the art history you’ve absorbed. In early pandemic no one was watching. I didn’t have any shows lined up. So, in a way, I was totally liberated.

I was working at this really fast clip. I had to work in complete darkness because I’m working with the chromogenic paper, which is totally light sensitive. I wasn’t able to totally black out my studio, and of course I couldn’t even have a safe light, so I had to work at night when there was no sunlight. I’d had some insomnia in the pandemic, and I was going to sleep when my then five-year-old son was, at eight p.m., and then I was waking up at three or four in the morning. This became my prime time. I think it’s really kind of a famous time of day for, like, mother-artists’ work. I think Sylvia Plath called it the blue hour—you know, before anyone wakes up, where you actually have time to yourself. I felt that really viscerally.

Bengal: I love those times. They can be super generative and freeing when the rest of the world is turned off. You have a beautiful artistic relationship to night, too, that’s there in your 2015 series Moon Drawings. Were there other discoveries you made from working these hours?

Schneider: Before I was a photographer, I studied painting, and so when I started this work, I was thinking about Sigmar Polke and the way he just exhausted motifs. He would appropriate something from somewhere and just make hundreds of photocopies of it, and they’d show up in paintings, these serigraphic images. It’s this different sort of engagement with Polke. It’s not like Warhol; it wasn’t a commentary on mass media or anything. It was just the weirdest, most idiosyncratic stuff. It emboldened me to do the same thing, and then there was this moment where I realized, Oh, these images that I’m reproducing, what if I then rephotographed those and those kind of invert yet again, and then I invert them again. I was really immersed in it.

Bengal: So much of your work is cinematic in feeling and in origin, embodying these ideas that go back to Laura Mulvey, who introduced this idea of the male gaze—viewing a woman’s image as sexual object or giant threat.

Schneider: I’d had a Zoom studio visit with my friend Sarah Lookofsky, she had also studied with Laura, like I did at the Whitney Independent Study Program. And as we were talking, she said, “Have you read Laura recently? Maybe you should read her again.” And it was like, Oh my god, you’re so right. I mean, I hadn’t, like, in a decade. I went back, and I saw that the new work was illustrating this. It was so bizarre. Obviously, this was part of the armature upon which I’m building this work when I’m working intuitively, but it wasn’t conscious at all. When I reread her texts, I was just smacking myself on the forehead. You couldn’t do that, in a sincere way, to illustrate theory, but it felt so unbelievably parallel that I reached out to Laura and asked her if she’d meet with me on Zoom. We’ve had an ongoing conversation since then. She’s so sharp, and she’s writing about so many other things, too, and also updating texts she wrote that are now, like, forty-five years old.

She was telling me the other day how she was screening Citizen Kane for some people and when she was loading the film, it unspooled. It just spilled everywhere—but it also retained this form of the coil. There’s chaos, but it also somehow retains its form.

Bengal: Which was surely messy and maybe a little horrifying in the moment. But, as I also see it in the unspooling of your Sphinx, so vulnerable and exciting, to just lay it all bare and be. I think there’s a power in that. I also wanted to go back to something you said earlier, where you described your “alphabet of imagery.”

Schneider: I call it a seed-library impulse. At the start of making this work I was reading Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, as so many people were. So, just the idea of preserving these creative influences, whether they were my peers or mentors or just different canonical works in the history of art, like this very idiosyncratic collection, but kind of preserving them in an analog form, just in case the digital technology could fail. There was something doomsdayish about it.

I also thought about it as, maybe that Mariah Carey clip [present in Schneider’s recent exhibition at Chart, I don’t know her] is, like, the golden record. To preserve some aspect of human culture and make this analog, as if we were sending it out into space. Putting it into a tangible form was a way of making a big statement about wanting to possess it or preserve it in a way.

Bengal: It feels to me also like a reclamation. To make your own camera. To articulate your own language. To take that all into your hands. To repossess those images and retranslate how they are seen. The immense space that the sphinx and Romy Schneider and Spacek-as-Carrie and all these women occupy in these rooms.

Schneider: When I kind of scaled up my camera, I started working in a way that felt much more loose. But also, sourcing these original images, it felt like it was something that could spin outwardly forever into these infinite possibilities, like in the way Agnes Martin could infinitely source a grid. For her the grid was so innocent and pure, like a tree. I felt like there was this really beautiful thing where I thought: I don’t have to go any further. I have it all right here, in this cache of images.

But also: if it is autobiographical, I think about the way Lauren Berlant said that the autobiographical impulse is inherently anxious and ambivalent. I think that’s kind of what drives it, that tension. There’s an element of possession and homage, but also theft.

All photographs courtesy MASS MoCA

Bengal: How did the physical process of making those giant prints affect the way you felt about and understood your own work?

Schneider: The owner of My Own Color Lab, where I printed all of it, and all of the employees—they went out of their way, stayed late, would help me run these massive things through. And just seeing, you know, that they even allowed me to do that is so rad. But also, their excitement about it was so motivating. I think it goes back to using all these technologies that require a lot of material knowledge but then using them in a way that they’re not meant to be used. That spirit of experimentation just made it all possible. The fact that they were even game to let me try to do it and were so psyched about it.

Bengal: There’s this inherent spirit of rebelliousness about that. How far can you extend this idea?

Schneider: What if this could just go on to infinity?

Carrie Schneider: Sphinx was on view at Mass MoCA through September 17. The accompanying catalog was published in 2023 by Hassla.