Collecting the Japanese Photobook

Ryuichi Kaneko interviewed by Ivan Vartanian

Ryuichi Kaneko is a leading historian of Japanese photobooks, and over the course of four decades he has amassed a formidable collection of twenty thousand volumes, including magazines and catalogues. In his role as curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, from its nascency up until this year, he oversaw the development of the institution’s public collection. As a scholar, Kaneko has been an important figure in supporting and extending scholarship surrounding Japanese photography and photobooks. Ivan Vartanian, who guest edited the latest issue of The PhotoBook Review, spoke to him about how he became one of the first and most enduring champions of the Japanese photobook, the evolution of the form, and what makes a book irresistible. This article also appeared in Issue 6 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

Ivan Vartanian: You began collecting books at a time when no one else had interest in Japanese photobooks. How and why did you start?

Ryuichi Kaneko: It started in high school and university, when I was taking photographs and realized I possessed absolutely no talent for it. But I loved photography. My father was an amateur photographer, and after the war he worked as an editor at a fashion magazine, which influenced me too, with all the exposure to material it provided. Since I couldn’t make images, I thought intensely about what I could do that would connect me with the world of photography, and started to just consume and absorb whatever materials I could get my hands on. Photobooks were a vehicle for that.

The first Japanese photobook I ever purchased was Otoko to onna [Man and Woman, 1961] by Eikoh Hosoe. And the first book I purchased by a foreign photographer, in 1967 or ’68, was William Klein’s New York [1956]. Around that time, 1967 or ’68, I started to become acquainted with a lot of photographers, and by 1974 or ’75 I started to buy books actively.

Kazuhiko Motomura is a publisher and editor who made Robert Frank’s The Lines of My Hand [1972] with Yugensha. When I ordered a copy of the book, Motomura delivered it by hand to my door. And from there started a long friendship and a sort of mentorship. He introduced me to a slew of photographers, bookstores, and bookstore owners, particularly in the Kanda area of Tokyo. After that, Kanda became my library, where books and magazines could be bought. My passion became my mission.

And it was just about this time that independent galleries were operating in Tokyo. To the photographers in these places— which were hangouts as much as they were noncommercial exhibition spaces—I became known as the guy who had all these photobooks from Japan and the West. It was an opportunity, or excuse, if you like, to talk to photographers and be connected to the medium that I loved so much. For example, at Photo Gallery Prism, I met photographers Hitoshi Tsukiji, Kineo Kuwabara, and Hiroshi Yamazaki. At Image Shop Camp, I met Keizo Kitajima. These photographers were of the same generation as me. That was an important point because they had an antiestablishment way of thinking.

IV: So what was the experience of buying photobooks at that time?

RK: It wasn’t simple. There weren’t a lot of photobooks by Japanese photographers. And of those that were in existence, only a handful were worth buying, like Shomei Tomatsu’s Taiyo no empitsu [The pencil of the sun, 1975] or Kikuji Kawada’s Sacré Atavism [1971]. But there were several gems from the West: Lee Friedlander’s Photographs [1978], Garry Winogrand, Nathan Lyons, and Bruce Davidson, as well as Aperture’s Paul Strand and Walker Evans retrospectives. There was also Dorothy Norman’s book on Stieglitz, An American Seer [1973], which I went around and showed to everyone, and it changed our impression of Stieglitz. It was this process that led me to become interested in the history of photography, too.

IV: After the mid-1970s, with the proliferation of photobooks, were you able to keep up?

RK: I bought pretty much ninety percent of everything that was published then. I don’t think you can imagine this: I would go to Kanda twice a week, and then Waseda, to visit used bookstores. And of course Shinjuku’s Kinokuniya bookstore. Unlike now, when there is a surplus of books, at that time there weren’t many Japanese photobooks to buy. How could I use the ¥10,000 I had in my hand? There were days when I couldn’t find a single book to buy and would go home feeling dejected.

IV: Were there any other people buying photobooks at that time?

RK: No! There was no one else.

IV: So how did this culture of collecting books grow in Japan?

RK: It’s thanks to me and Kotaro Iizawa. He, too, was studying Japanese photo history, and when we eventually met we realized we were both doing pretty much the same thing at the same time. Iizawa often said that we needed to change the culture from the enjoyment of taking photographs to the enjoyment of looking at photographs. That was in the first half of the 1980s, just before I started working at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. But the culture of actually enjoying reading Japanese photobooks didn’t evolve until after the 1990s. The 1980s were about foreign photobooks, but I was a cheerleader for Japanese photobooks.

IV: Were there any dramatic shifts in the form of Japanese photobooks between the 1960s and the ’80s?

RK: No, except for the dramatic improvements in printing technique. It was something that became apparent later. There was gravure printing in the beginning, after the war, and then after the 1970s it was all offset printing. But there still wasn’t this sense that a photobook was a function of its printing. That would be entirely the influence of the American photobook, which was recognized in Japan in the 1980s.

IV: Japanese photobooks have special value as the vehicles by which a lot of Japanese photography has been seen by the West. Do you think some distortion has resulted from this, by not seeing the prints themselves and only seeing the work in the form of photobooks?

RK: In Japan the photobook has had special significance for photographers from the 1930s onward; from the 1950s to the 1970s, there was a widely accepted understanding that there were certain modes of expression that could only be achieved in the form of a photobook. The print was forgotten to a certain degree. And when it came to academic matters of collecting, which is what I did as a curator for the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, the first selection of images was often based on what was in photobooks. Quite frankly, many Japanese photographers are quite unconcerned with how work is shown in a gallery setting because the photobook is already out in the world and circulating among people.

It is precisely because of this imbalance that Japanese photobooks have their unique sensibility and can achieve new levels of expression. A great example of this would be the 1963 version of Eikoh Hosoe’s Barakei, which was printed in gravure. You could cut those pages out of the book and frame them. One shot of Yukio Mishima staring into the camera at close range has not only become a symbol of that body of work, it has become iconic. So when the prints from that series are sold, that image gets prominence over the other images, and the book’s context and complexity get lost.

IV: So how about contemporary photobooks? Are you actively collecting those too?

RK: [laughs] To be totally frank, it’s no different from the situation I was facing back in the 1970s. It’s very difficult to find a book I feel I must own. There are a lot of books out there now, which is like a dream come true, but sadly only a few make it into my collection. There are few books that communicate an innate need to exist, or to even be a photobook to begin with. Then there are the books that you just take one look at and know, “I must own this.” That’s what I’m looking for when I visit bookstores.

Ryuichi Kaneko is a critic, historian, and collector of photobooks. He has authored or contributed to numerous publications, including Independent Photographers in Japan 1976–83 (Tokyo Shoseki, 1989),The History of Japanese Photography (Yale University Press and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2003), Japanese Photobooks of

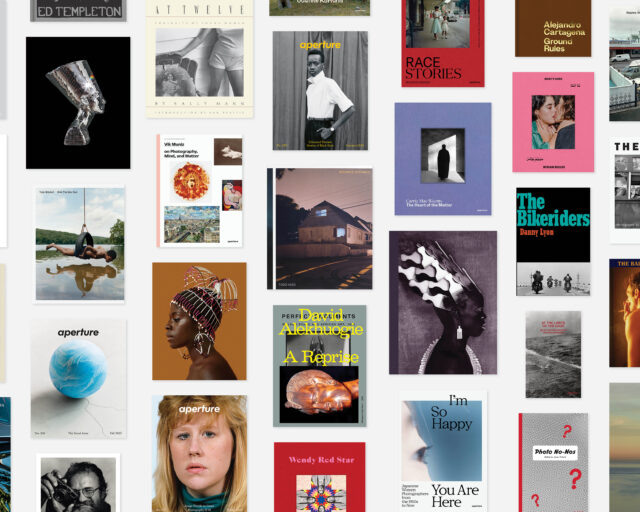

the 1960s and ’70s (Aperture, 2009), and Japan’s Modern Divide (J. Paul Getty Museum)