"Conflict" at Krakow Photomonth 2015

Writer Aaron Schuman reports from this year’s edition of Krakow Photomonth, an annual photography festival held in institutions, galleries, and spaces around the city each June. Schuman reflects on this year’s theme of conflict.

Josef Koudelka, Czechoslovakia, August 1968; from the series Prague, 1968.

Established in 2002, Krakow Photomonth has grown from a rather rambunctious and rebellious upstart—packed into disused buildings, artist squats, crowded bars, and burgeoning galleries—into one of the most ambitious and engaging festivals on the photography calendar, now staged in some of the city’s most prestigious museums and exhibition spaces. In recent years, its various programs have consistently presented thoughtful and challenging shows on a wide range of themes, including ruminations on artistic use of a fictional identity, in ALIAS (curated by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, 2011); to experimental takes on Photography in Everyday Life (curated by Charlotte Cotton and Karol Hordziej, 2012); to investigations into The Limits of Fashion (curated by Paweł Szypulski, 2013); to explorations of the complex relationship between photography and information in Re:Search (curated by myself, 2014). This year’s edition, which ran from May 14 to June 14 and was devised by Wojciech Nowicki, a celebrated Polish essayist, novelist, critic and curator, revolved elegantly and elliptically around the central theme, conflict.

Festival poster for Krakow Photomonth 2015

In part, the seventy-year-old specter of Soviet aggression—resurrected and made real again with the current crisis in neighboring Ukraine—loomed subtly (and at times, not so subtly) over the festival. At Starmach Gallery, a renovated nineteenth-century synagogue that now serves as one of the city’s most distinguished commercial art spaces, Josef Koudelka’s legendary body of work, Invasion Prague 1968, served as a reminder of the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, and the non-violent protests and impassioned resistance that erupted in the streets of Prague during the week that followed, which ultimately failed to prevent the Russians from ostensibly ruling over the country for the next thirty years.

Frederic Lezmi, Taksim Calling (self published), 2013; installation view of TRACK-22: Photobooks on Conflicts at Bunkier Sztuki Gallery of Contemporary Art (photograph by Aaron Schuman)

In Track-22, curated by the publisher and founder of The PhotoBook Museum, Markus Schaden, and held in the imposing 1960s brutalist masterpiece, Bunkier Sztuki, photographic engagements with more recent political uprisings and protests surfaced, including those staged in Istanbul’s Taksim Square (Taksim Calling by Frederic Lezmi, 2013), Kiev’s Independence Square (Maydan: Hundred Portraits by Émeric Lhuisset, Barricade by Julia Polunina-But, and Euromaidan by Vladislav Krasnoshek and Sergiy Lebedynskyy, 2014), and elsewhere. The dynamic installations of these series, and several others, specifically called attention to the potency of contemporary photobooks that deal with such matters, which Schaden argued “counter anonymous and delocalized media coverage . . . have a distinct authorship, and are capable of tracking and witnessing conflict from a genuine point of view . . . through visual dramaturgy and materiality.”

Indre Serpytyte, I, 2009; from the series Forest Brothers

Indre Serpytyte, 7 Margio street, Alytus, 2014; from the series Former NKVD, MVD, MGB, KGB Buildings

At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow (MOCAK), a stunning new arts complex that opened in 2010 on the site of Oskar Schindler’s Factory, was 1944–1991 by Indre Serpytyte. Including two bodies of work—Forest Brothers (2009) and Former NKVD, MVD, MGB, KGB Buildings (2009–15)—the exhibition testified in a discreet yet powerful manner to the Lithuanian dissidents and guerrillas who fought against Soviet rule throughout the second half of the twentieth century, despite being subjected to imprisonment, torture, and murder by the Soviet security services.

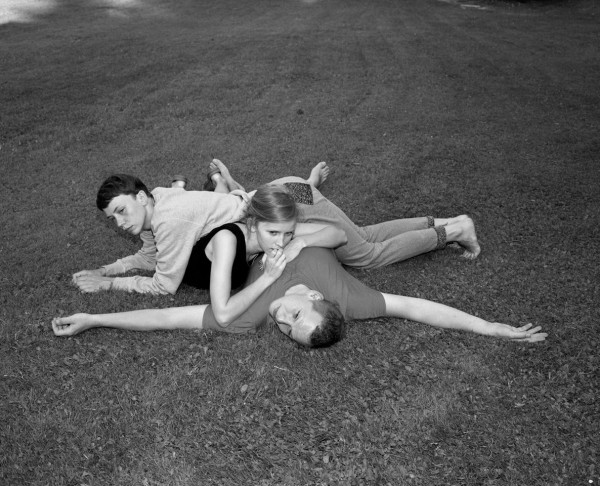

Joanna Piotrowska, XXIII, 2013–14; from the series Frowst

Elsewhere Nowicki’s take on the concept of conflict stretched well beyond the boundaries of politics and war, offering refreshing possibilities as to what could be deemed “conflict photography” today. “Conflict does not mean only armed clashes,” Nowicki explained in the festival’s introductory statement. “Often, conflicts are played out only in someone’s imagination, and consist of gestures, or even memories, that are difficult to capture.” Such sentiments surfaced in surprising ways in Joanna Piotrowska’s Frowst (2013–14), exhibited at the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow, which portrays suppressed yet discernable familial tensions through the physical contortions and awkward body language of her subjects, all of whom are immediately related.

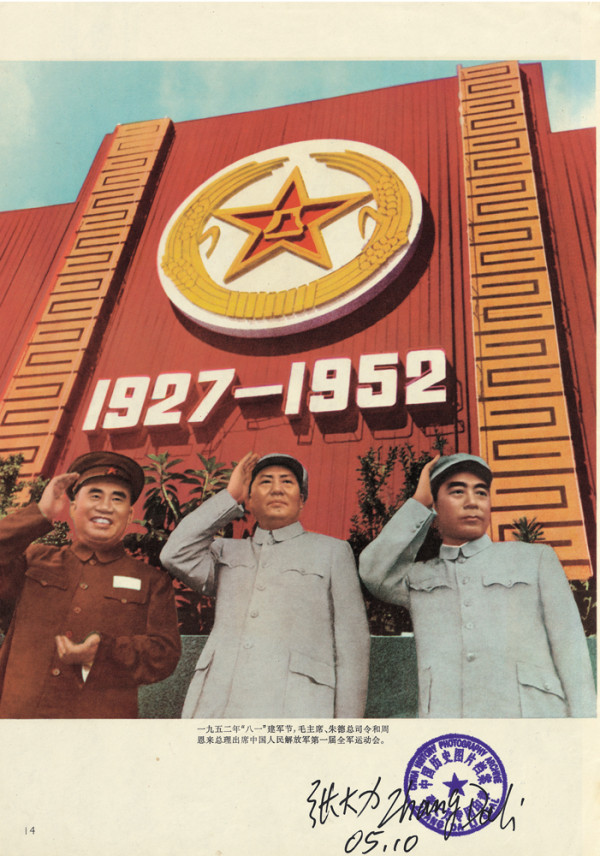

Zhang Dali, The First Sports Meeting of the People’s Liberation Army, 1952. (from the series, A Second History)

At the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology, Zhang Dali’s A Second History explored the doctoring of official photographs in Mao-era China, forensically dissecting the menacing and ridiculous ways in which images deemed in conflict with the Party line were manipulated in order to reflect an acceptable Maoist “reality.” The most unexpected interpretations of the festival’s theme came with Paweł Szypulski’s exhibition, Foreign Body, which brought together a trove of materials—ranging from video clips from Nicki Minaj’s Anaconda, to Leni Riefenstahl’s book, The Last of the Nuba, Kodak’s “Shirley” color-test cards from the 1950s to the 1990s, a 1972 Playboy magazine that served as the source of the standard referencing photograph (dubbed “Lenna”) used in testing image compression algorithms, to a YouTube video entitled HP Computers Are Racist, to Eugène Atget’s photograph of the Callipygian Venus (“Venus of the Beautiful Buttocks”) at Versailles, to footage of Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston topless, and more—presenting a stunning example of curatorial choreography in which intriguing histories and uncomfortable relationships between gender, race, photographic technology, and visual culture at large were exposed in the most entertaining and enlightening of ways.

Ultimately, Krakow Photomonth 2015 represented how a photography festival, when given the freedom to embrace ambition, complexity, and experimentation, can offer thoroughly new insights and engage audiences far beyond expectation. The experience was both an inspiring and a dizzying one, raising difficult questions and contradictions, which likely left visitors feeling satisfyingly conflicted—and surely that was the whole point.