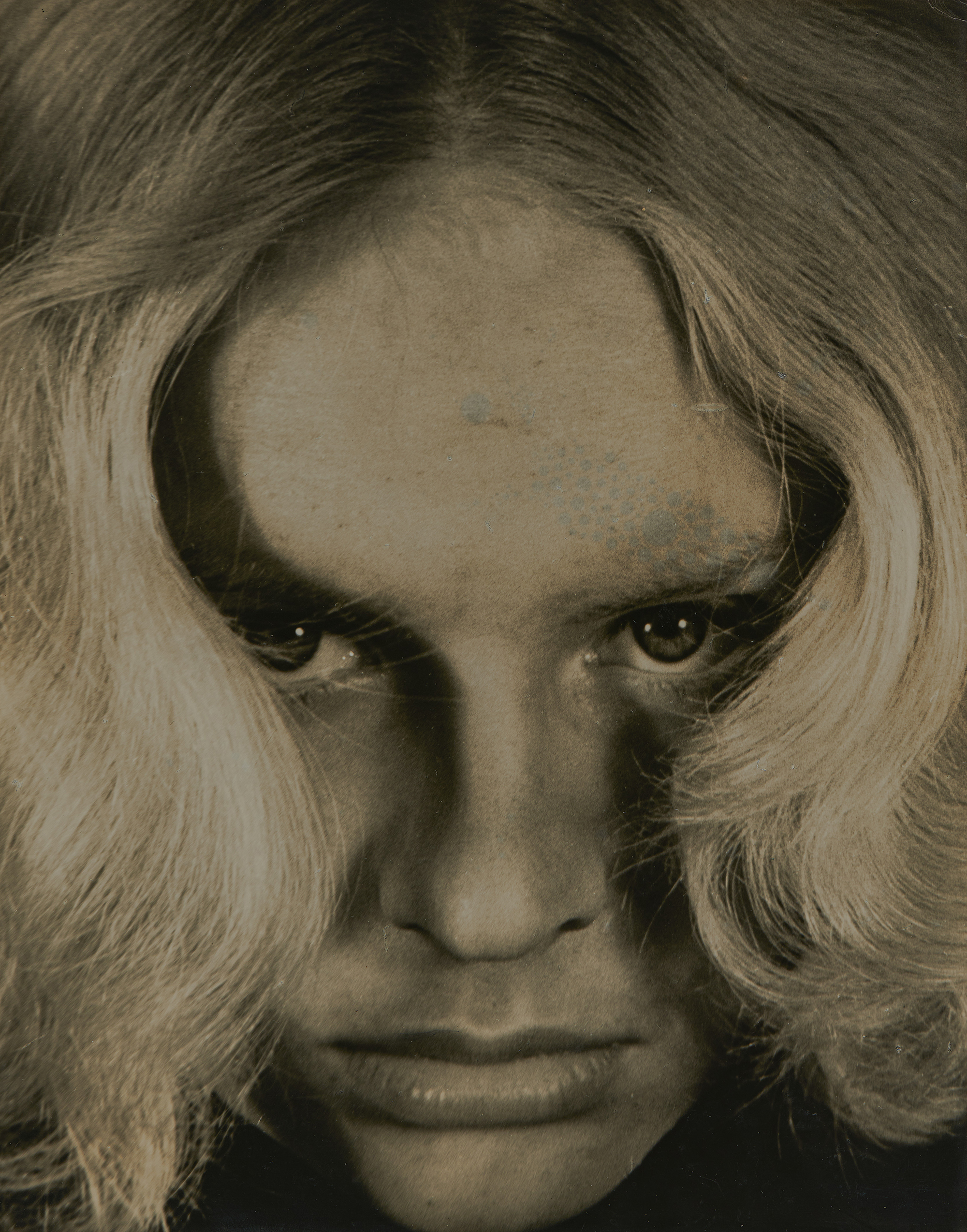

Consuelo Kanaga, Young Girl in Profile, 1948

Over six decades, Consuelo Kanaga, born in 1894, forged a career defined by an avant-garde, collaborative spirit and a photographic practice tied to social justice. In her home cities of San Francisco and New York, she was at the heart of close-knit circles of artists and writers, namely the California Camera Club, Group f.64, and The Photo League. She was an ardent documentarian of the Worker-Photography and New Negro movements of the 1920s and ’30s and the civil rights movement two decades later. It’s therefore confounding that in the years since her death, in 1978, Kanaga’s name and legacy, compared to those of her celebrated friends and contemporaries—Alfred Stieglitz, Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Tina Modotti, and Louise Dahl-Wolfe—have fallen into obscurity.

A retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, Consuelo Kanaga: Catch the Spirit, endeavors to introduce the photographer to a new generation and reestablish her place in the canon of modern American art history. Organized by Drew Sawyer, a curator of photography at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the exhibition first appeared at the Fundación MAPFRE in Barcelona and Madrid, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. With organizational support from Pauline Vermare, the show concludes its run at the Brooklyn Museum, the institutional home to some five hundred prints by the artist as well as many more negatives. Catch the Spirit generally follows the chronology of Kanaga’s life and career, but Sawyer groups the nearly two hundred photographs and contextual pieces of ephemera by style and subject, so that the viewer can sense the artist’s creative restlessness, exceptional versatility, and recurring preoccupations.

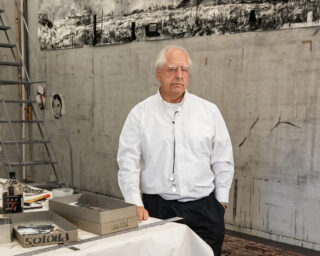

Kanaga’s practice began when she was working as a young reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, an unconventional profession for women in the 1920s, and she discovered a penchant for directing the photographs that accompanied her articles. Encouraged by her editor, she began hauling the large-format view cameras of the day out to the field and shadowing colleagues in the darkroom. In the Brooklyn Museum installation, this photojournalism—penetrating scenes of poverty and tragedy in the twentieth-century American city—appears alongside portraits of wealthy clients and fellow artists that she made on the side. These are daring exercises in straight photography, made hauntingly beautiful by the almost surgical application of cropping and chiaroscuro.

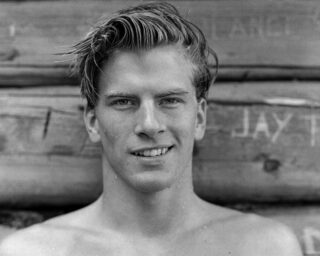

Kanaga favors dramatic closeups. Her gaze captures the piercing blue eyes and supple lips of an androgynous blonde studio model in Untitled (ca. 1925) and the dark, imploring eyes and sunken cheeks of a poor little boy, a recurring journalistic subject, in Malnutrition (1928) with the same devotional intensity. It takes a delicate boldness to get that close to a subject, and an impish curiosity. Kanaga wants to know them, through their faces and hands. Hers is a necessary violation, a shedding of the external signifiers binding her subjects to the realities they suffer. At times, her composition and framing are in service of sly allusions to the biblical and art historical, as in the deprived Madonna and Child of Untitled (New York) (1922–24) and the three mourning Fates of Fire, New York (1922), finely rendering the human experience specific and universal.

In the late 1920s, Kanaga made a sojourn through Europe and North Africa that shifted her work from documentary photography to liberated image making. She took inspiration from French and Italian painting, like the Pictorialists before her, and even tried her hand in watercolor. She felt challenged by photomontage, which was all the rage in Germany and Austria. In Tunisia, she was struck by otherworldly light and towering minarets. In portraits of the Kairouan locals, she eschewed anthropological and orientalist trappings, capturing them as she did the people back home, in their candid fullness. A smile or a glint in the subject’s eyes, as in those of the young woman in Young African, North Africa (1928), tell of an intimacy that has been broached and kindled.

“I would sacrifice resemblance any day to get the inner feelings of a person,” Kanaga wrote home to her friend and patron Albert Bender. “It seems so much more of one than our face which is so often just a mask.” In the darkroom, she mixed formulas to achieve specific tones, experimented with burning and overexposure. She traced lines over a printed image with graphite, or smudged them altogether. She cropped prints and negatives with equal ferocity. All of this, a calibration of drama with dignity, or the feeling of connection to the subject with implication and self-awareness on the part of the viewer.

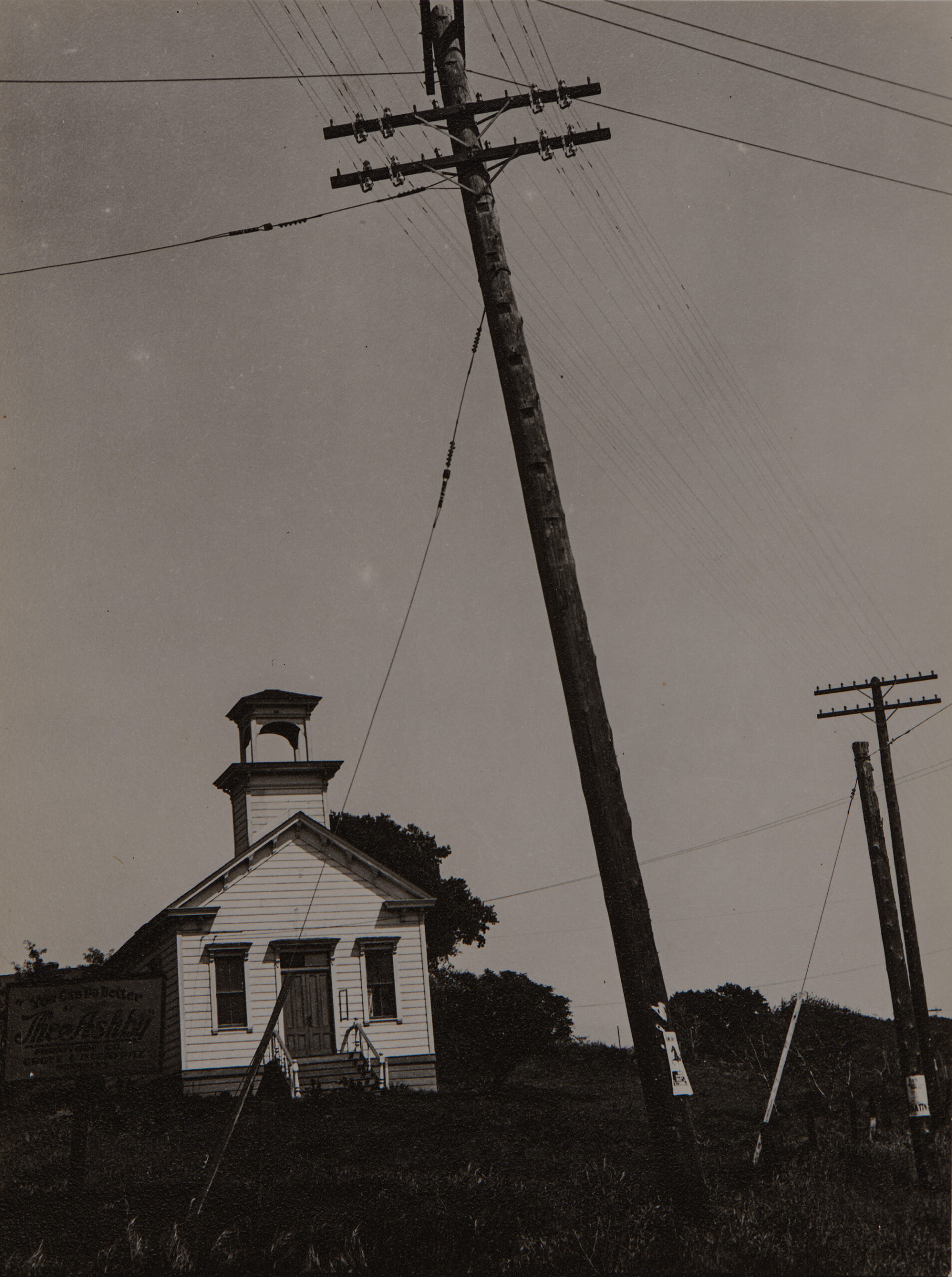

Time blurs magnificently at the midpoint of the show, a delightful interlude of Americana still lifes, landscapes, and abstract nature studies, showcasing Kanaga’s compulsion to push her medium to its limits. Mostly devoid of human subjects, the pictures are charged with her wit and worldview. The lipped porcelain pitcher in Untitled (1925) is a reclamation of the libido from the exploitation of capital, represented here by the hard-edged bar of Ivory soap. The Abstraction and Untitled series (1948), snapshots of the reflective surface of the pond by the Yorktown Heights home Kanaga shared with her husband, the painter Wallace B. Putnam, like Monet’s water lilies, occupy the threshold between the material world and the divine.

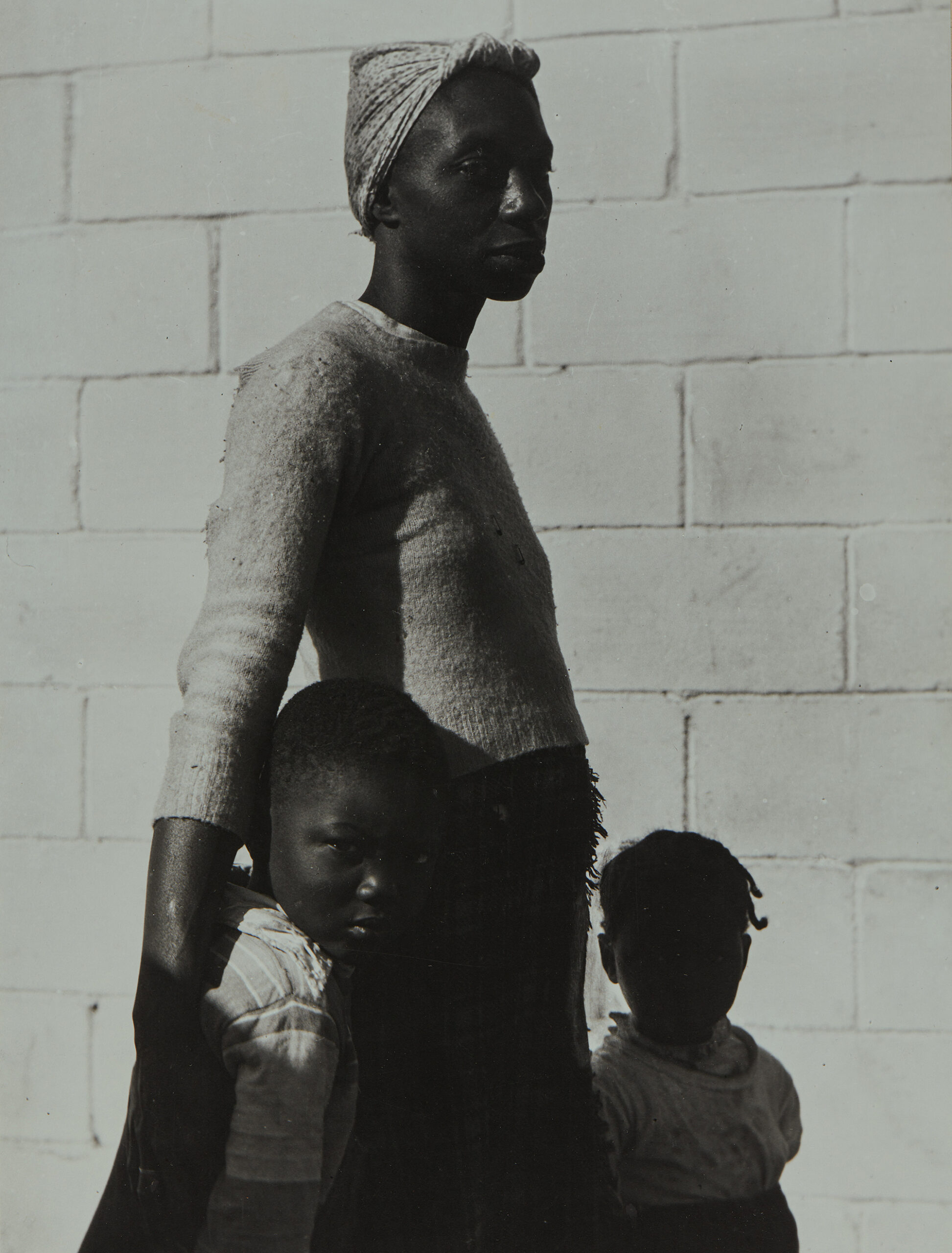

Among Kanaga’s most important works is She Is a Tree of Life, II, Florida (1950), which she made during a visit to the mucklands of Florida, where migrants worked the fields, picking lettuce and other vegetables. She had spent the day with her subjects, a mother and her family, learning about their life and toil, taking several pictures. This composition, practically sculptural, arrived in their parting moments when the light was just right. It would be immortalized in Edward Steichen’s landmark Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1955. “This woman has been drawing her children to her, protecting them, for thousands of years against hurt and discrimination,” Steichen captioned the photograph. The image is a technical study of contrasts, epitomizing Kanaga’s trademark blend of social documentary and expressive pictorialism.

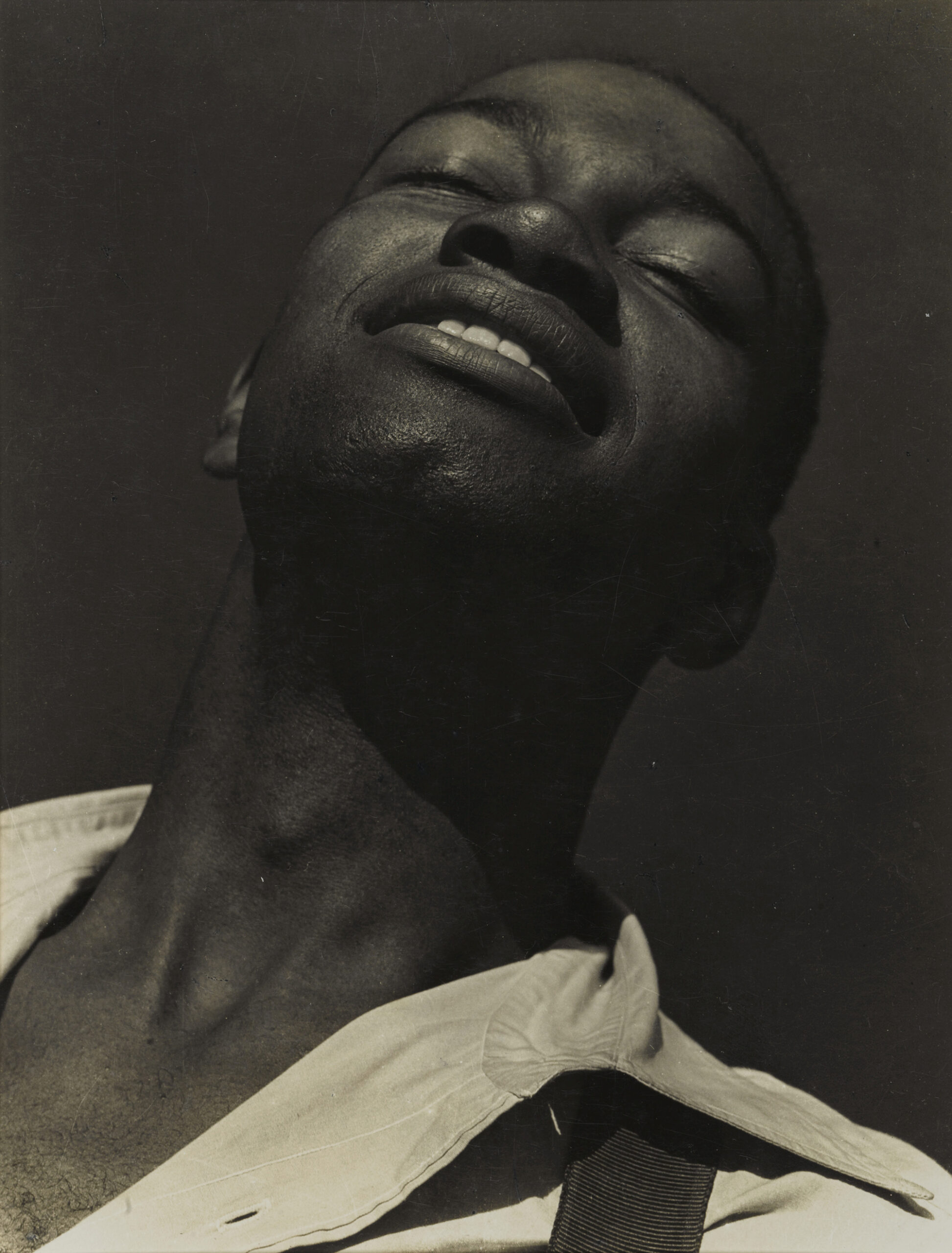

Kanaga’s early descriptions of her affinity for Black subjects can sound naive, paternalistic, or overly romantic. Yet, in a time when discrimination was law and racial terror was ever-present, she aligned her work with Harlem Renaissance artists and intellectuals, celebrating Black beauty and self-expression while pushing for progressive reform. Many of these portraits were collaborations with the subjects, not only in the studio, but in life as close personal relationships. Kenneth Spencer (1933) is a tight close-up on the actor and singer. His head is lifted, soaking in the warmth of what appears almost like stage lighting. If you were to zoom out of the frame, he could be, blissfully, mid-pirouette. The poet is in repose on a méridienne in Langston Hughes (ca. 1934), Olympia in a smart suit, a playful assertion of the freedom to move between the worlds of desirability and respectability. Eluard Luchell McDaniel (1931) cradles Kanaga’s family friend and constant muse (the San Francisco police once detained them for driving in a car together). Eluard rests his head on the grass, hands pressed against his cheeks, eyes closed in unburdened tranquility. In these final rooms of Catch the Spirit, there is a surge of both fiery passion and gentle uplift.

All photographs © Brooklyn Museum

Kanaga’s final assignment as a photojournalist, a favor for her friend, the poet Barbara Deming, was to document the Quebec-Washington-Guantanamo Walk for Peace, a series of marches, from 1963 to 1964, for Black liberation and in protest of the Vietnam War. The photographs, some of which Deming later published in Prison Notes, harken back to Kanaga’s early days of straight photography. Yet, even at this late stage, she could not resist the application of painterly flourishes. Dramatic shadow throws the smiling titular figure of Ray Robinson, Albany, Georgia (1963) into stark relief. While his more solemn comrade holds out an open palm, curved and questioning, Robinson’s arm grips with assurance a suitcase with the acronym “CORE,” for the Congress for Racial Equality, and the phrase “LOVE FORGIVES,” from Corinthians. The image is taken from a low angle, so the figures are elevated. Behind them are bare trees, leafless tendrils reaching to the sky.

Catch the Spirit arrives in a season of diminished public welfare, deportations of lawful residents, and criminalization of dissent, all government sanctioned. Kanaga’s creativity and conviction, therefore, feel especially timely, and the exhibition a call to action, as well as a case for beauty in the face of adversity. “I don’t feel I’m young enough to stand the rigors of peace walks,” Kanaga, who was almost seventy and suffering from emphysema, said about marching with the coalition of young people in Georgia, Black and white together. “But I’m heart and soul for peace and integration and if my camera can be of help, I want to use it to the fullest.”

Consuelo Kanaga: Catch the Spirit is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through August 3, 2025.