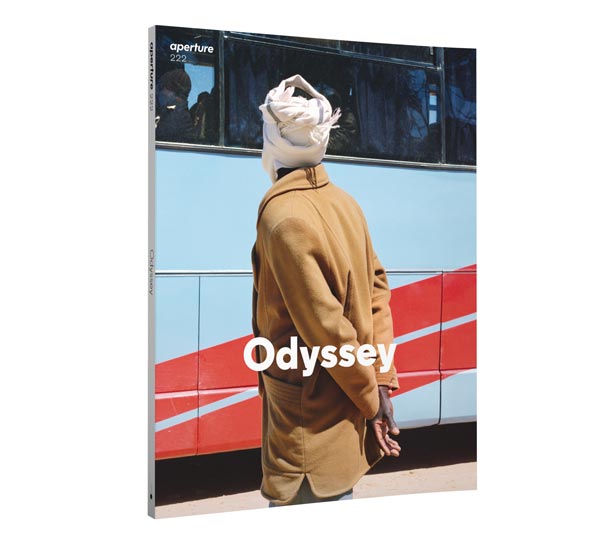

On the Cover: A Conversation with Samuel Gratacap

The Spring 2016 issue of Aperture features a cover image taken by Samuel Gratacap at a transit camp in Tunisia. Since 2007, the 32-year old French photographer has followed the lives of refugees and migrants crossing the Mediterranean, documenting moments of departure—and the emotions of waiting—at sites including the Italian island of Lampedusa and a detention center in Marseille, France. At its peak of operation, the transit camp at Choucha, where his series Empire is set, received upwards of 200,000 migrants, many fleeing the crisis in neighboring Libya and others escaping conflicts in West Africa and Southeast Asia. One of the most pressing debates of current international consequence, the flow of political and economic refugees toward an elusive haven in Europe has been the subject of intense coverage in news media and photojournalism. Resisting the sensational, however, as Bronwyn Law-Viljoen writes in her introduction to Gratacap’s work in Aperture, “There is beauty in his images, but also an attempt to understand the bare-life fact of Choucha, and to avoid consigning the camp’s inhabitants to the realm of the poetic.” I spoke with Gratacap late last year, shortly after he returned from a reporting trip in West Africa for Le Monde. —Brendan Wattenberg

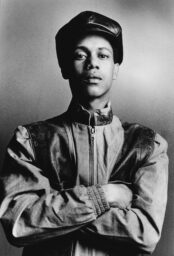

Samuel Gratacap, Departure day, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

Brendan Wattenberg: Do you consider yourself a photojournalist and an artist? How does your reporting on current events influence your long-term projects?

Samuel Gratacap: I’m a photographer. The main thing that pushes me to be more and more involved is the importance of the mass media in representing the topic of migration. Mass media should be concerned with making the complex issues around migration visible, but instead it is limited to making so-called news. However, some photo-editors are starting to create new ways of editing and publishing photography—at Le Monde, for instance—such as double pages dedicated to photography in the print version and portfolios online. For me, jumping between long-term projects and photojournalism is just a way to challenge my own practice, to find new fields and new forms of expression.

BW: Before Empire, you were already working on migration as a theme in Castaways and La Chance. What prompted you to become so interested and involved with this issue? How does Empire extend your previous work?

SG: Photography becomes interesting when making pictures is a difficult process, primarily for reasons of accessibility. I first became involved with migration issues when I was a student at the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Marseille. La Chance (2007–2012), my first series, is a project I created in 2007 in a detention center in Marseille for “illegals.” The underlying reason for my decision to enter the detention center was the desire to understand the conditions of imprisonment and the judicial system in France with regard to undocumented immigrants. I felt like I was moving away from reality by reading newspapers and publications that distorted figures or images, anonymous and impersonal testimonies. I wanted to go in search of a reality on a human scale, make it visible, define the contours of individual stories beyond the numbers, flows, and figures.

Samuel Gratacap, Detention Center for Migrants, Zaouïa, Libya, 2014

Castaways (2007–2016) follows seven years of work about places of confinement and transit areas related to migration routes in the Mediterranean region. The idea is to reverse the concept of borders and create a proper map, within which emerging destinies and random trips take place. Having recorded the testimonies of migrants and asylum seekers throughout my travels, I’ve noticed that it’s often at the cost of freedom of expression and reduction of their basic rights that people choose to leave their country of origin. “Undocumented,” they are forced to hide. They fall into complete anonymity, finding themselves in constant struggle with a system that doesn’t give them the chance to get out and get papers.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

Empire was my first long-term project. It was a natural extension of my previous work, but I had the desire to involve myself, like I had never done before, through a deep and immersive approach. It changed a lot about the way I photograph. I was already working on a project I started in southeast Tunisia, in the city of Zarzis, not far from Choucha. Zarzis was a port of departure for thousands of Tunisian migrants who fled to Italy just after the revolution in 2011. At the same time, the civil war and NATO attacks started in Libya. Hundreds of thousands of refugees moved to Tunisia, specifically to Choucha.

Choucha is symptomatic of the fate often reserved by the mass media for migration. These refugees and migrants went from an anonymous status to suddenly having the spotlight turned on them; they then became contemporary icons of what the media has too often presented as the “migratory drama.” But after the Libyan “crisis” and the death of Gaddafi, in October 2011, the media was much less interested in the fate of refugees. Set upon for a while, in an often spectacular time in which images play a crucial role, refugees became abruptly forgotten and undesirable.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: Empire is characterized by a form of guarded intimacy. The portraits and landscapes represent a closeness and immersion in the camp’s community. Still, you approach the story with the objectivity of an outsider. During the time you worked on Empire, how long would you stay at the camp? Did you live with refugees? How did you establish relationships and take testimonies?

SG: I first traveled to Choucha in January 2012 as a photographer accompanying a reporter. Confronted with the rules of short-term reporting, I faced difficulties in rendering an image. As a result, I decided to return to Choucha in July 2012 and start a long-term photographic and video documentary project. For two years I stayed a total of about twelve months in the field. I lived between the border city of Ben Gardane and the camp. A community of refugees from the Ivory Coast hosted me. I slept there during this time; I was very close to the people. This closeness was important for my understanding of daily life inside the camp. As my time in the camp passed, my photography evolved, but I wouldn’t say it was so intimate. I never considered myself an inhabitant of the camp. The main thing was to maintain a sufficient distance, to go further and push my work.

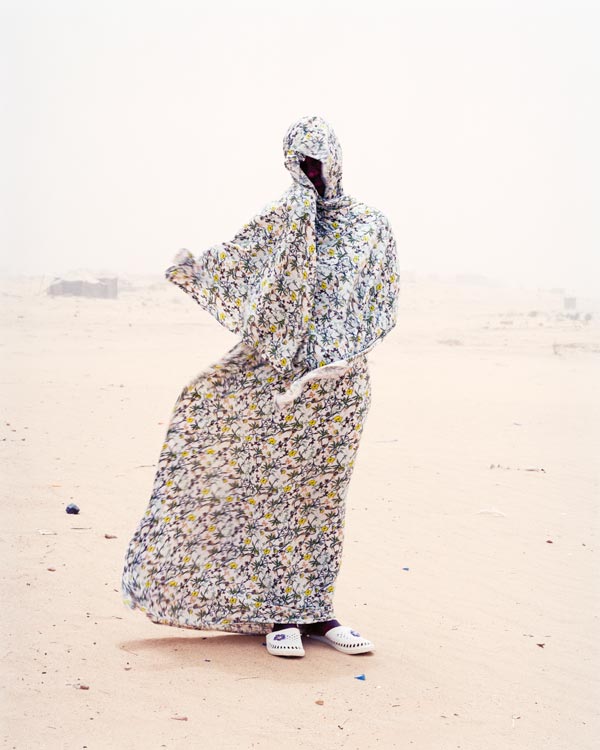

The reality of the camp was so complex; it was important to find a way to make it apparent, starting from a distance, and then getting increasingly closer. There is not one precise story of Choucha, but instead as many stories as the number of the people who’ve been there. I obviously missed some stories, some pictures. I forced myself to find the “right” approach and the “right” moment to document this place as the hostile environment it is. The desert, the sandstorms, the waiting, the everyday moments (the food, the hairdresser), the days of departure … Time passed slowly and people felt more and more abandoned until that decisive moment, in July 2013, when humanitarian organizations “closed” the camp and left more than three hundred people with no food, no water. Men, women, and children were rejected as asylum seekers.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: Even though Choucha is a “transit zone,” your photographs from the camp are mostly about the experience, as you say, of waiting. In fact, Karim Traoré, an Ivorian migrant who you interviewed, says that Choucha is full of “wandering souls.” The spaces they inhabit alternate between claustrophobic tents and wide-open desert horizons. In the image we’ve chosen for the cover of Aperture, of a man facing a bus, you capture a person seemingly at an impasse. Could you tell us what Choucha was like during your time working there?

SG: From 2012 to 2014, Choucha was still a refugee camp, but the living conditions had become worse and worse. The sand destroyed everything, cracking the fabric of tents that were too fragile. The wind swept everything away. This picture of a man walking in front of the bus leaving the camp is an image of a tearing, a prejudice. Departure days were both sad and beautiful for the fact that some people could go and some people no.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: In Empire and your previous series, you show quiet, often very personal scenes, such as a man having his head shaved in Choucha or young men seeking a moment of leisure in Zarzis. In contrast to news photography, which is concerned with action and conflict, why is it important to portray these moments between action?

SG: I try to portray these moments to reveal how people are occupying time. How life is still going on despite the difficulties people are facing. How they are organizing themselves to fight against the hostility of places they are passing through. At the camp, the body undergoes an “administrative” status. The evolution of the people in these areas often lasts for years: there’s zero stability; men, women, and children are in a state of precarious vulnerability. My work is about these territories of movement: the border crossings, the waiting zones for daily workers, the prisons. As well as the places related to the “rest” of the body, the paths toward a newfound identity. How does it feel when one person is, at the same time, not feeling at home and not being accepted as a foreigner? How does the body “store” both the rootlessness and the rejection?

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14

BW: How do these projects integrate photography, video, and postcards together with found materials such as personal pictures, maps, and journals?

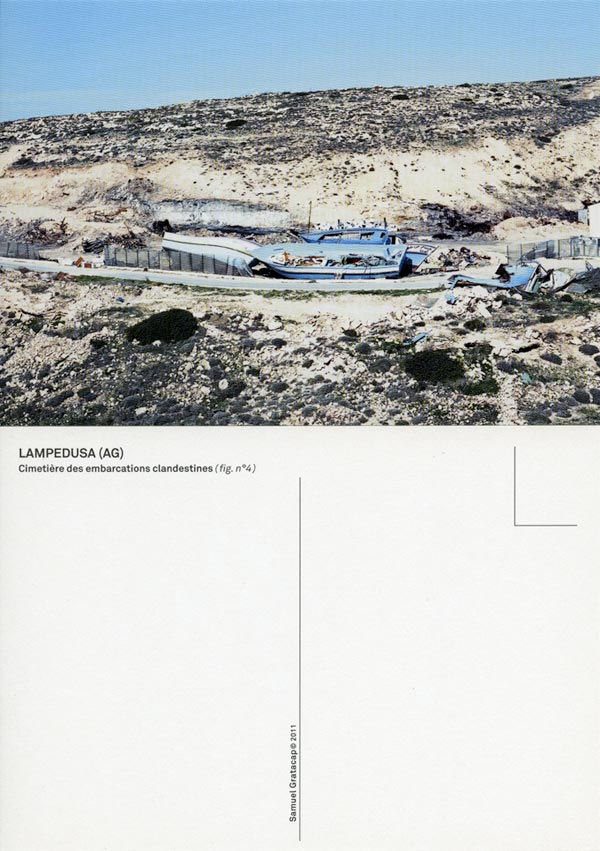

SG: The project to which you refer here, La Chance, is about the Italian island of Lampedusa, a place of shipwreck and a paradise for tourists. Lampedusa was a popular destination in the Mediterranean before becoming an emblematic place for the arrival of migrants by boat. With the series of postcards, I tried to reveal this paradox, showing the hidden side of the island. In parallel to this work, I created photographic reproductions of documents and photographs belonging to migrants, washed -up and recovered on the beaches of the island.

Samuel Gratacap, Cemetery of clandestine boats (fig n°4), Series of 8 postcards of Lampedusa, Italy, 2011

BW: Have you been able to stay in touch with any of the subjects of Empire? Have they seen your book?

SG: I stayed in touch with many people I met in Choucha. Some of them are still in the camp; some are in the capital, Tunis; some in Italy, in France. Social networks help to maintain contact. I think that only a few people I met in Choucha have seen the book yet, apart from some who are in Tunis and Paris.

Samuel Gratacap, Empire, Choucha Camp, Tunisia, 2012–14. All images courtesy the artist and Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire, Paris

BW: You are currently living between Paris and Tunisia and continuing to work in North Africa, particularly in Libya. What other projects are you working on now?

SG: I’m now pursuing my work about Libya and my assignments for Le Monde. The exhibition of Empire will travel to Tunis in 2016; this is the next step. At Le BAL, particularly through my project’s exposure in the press, I realized that the exhibition could reflect the situation of the refugees in Choucha for all visitors. That’s really important for me, because the project is about Tunisia. The camp still exists. People are still inside almost five years after their arrival.

Samuel Gratacap’s work is featured in Aperture Issue 222, “Odyssey.” Selections from his series Empire will be presented by Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire at AIPAD: The Photography Show from April 14–17, 2016 in New York.

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.