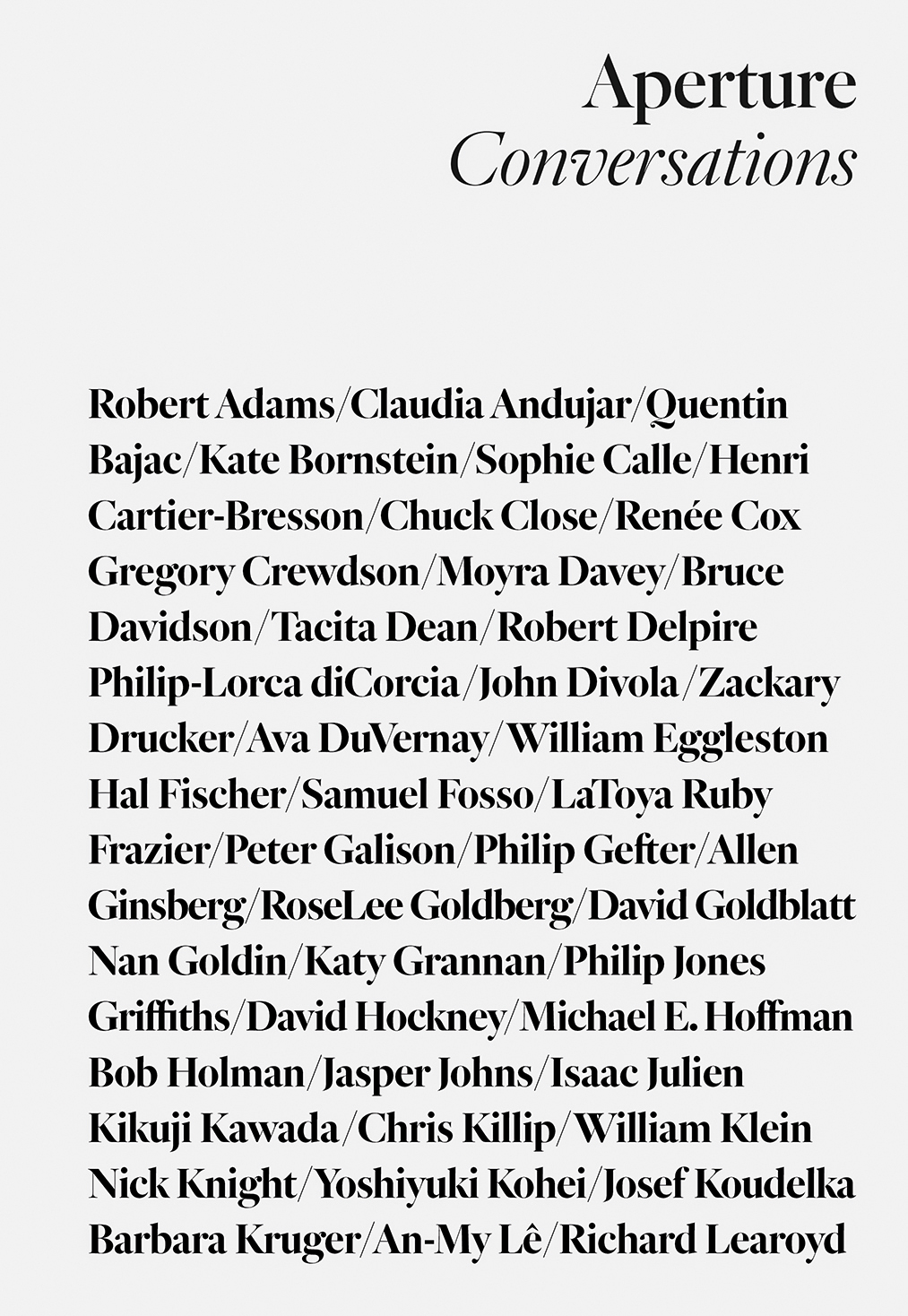

Daido Moriyama on the Unending Newness of Photographs

The legendary artist speaks about why photography never reaches a state of completion.

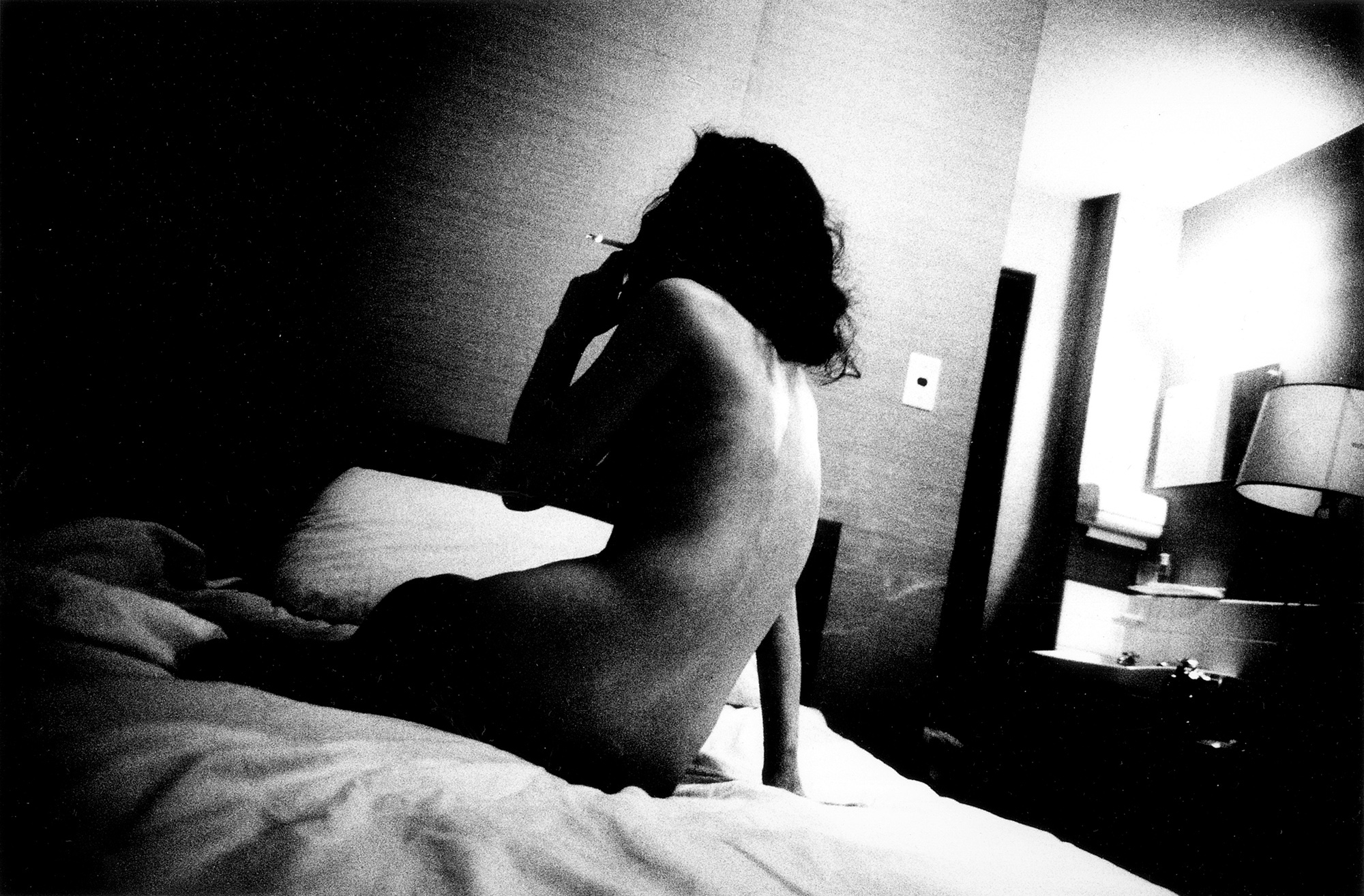

Daido Moriyama, from Labyrinth (Aperture, 2012)

Courtesy Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and Akio Nagasawa Gallery

Japanese master-photographer Daido Moriyama has been at the forefront of the medium for more than fifty years. He has published dozens of volumes of photographs, including Japanese Theatre (1968), Farewell Photography (1972), Daido hysteric (1993–97), and Hokkaido (2008), as well as numerous collections of essays. On the occasion of his retrospective at Osaka’s National Museum of Art, Ivan Vartanian spoke with the photographer about vision and motivation, context and information, color and black and white, and the unending newness of photographs.

Courtesy Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and Akio Nagasawa Gallery

Ivan Vartanian: Could you speak about your thoughts on the connection between image and language?

Daido Moriyama: Language is a direct medium and communicates meaning and intention straight. A photograph, on the other hand, is subject to the viewer’s memory, aesthetics, and feelings—all of which affect how the photograph is seen. It isn’t conclusive the way language is. But that’s what makes photography interesting. There’s no point in taking photographs that use language in an expository way. Taking photographs for the purpose of language is for the most part meaningless for me. Rather, photography provokes language. It recasts language; within it, various gradations outline a new language. It provokes the world of language: looking at images leads to the discovery of a new language.

That is what I am about. Certainly, photographers—in particular photographers like me, who take street snaps—don’t shuttle back to words with each shot. The outside world is suffused with language. I don’t carry language and apply it to the outside world; instead, messages come in from the outside. That is what provokes me and what I react to. That is the nature of the connection, I think. That said, I cannot explain every image that I have taken. If I tried to, it would be a sham and boring; it would come across as trivial. That’s not the intention. Each photograph is felt, but there isn’t just one reason for releasing the shutter— there are several reasons, even with a single exposure. The act of photographing is a physiological and concrete response but there is definitely some awareness present. When I take snapshots, I am always guided by feeling, so even in that moment when I’m taking a photograph it is impossible to explain the reason for the exposure. Something might, for example, seem erotic to me. That in itself is a gradation that contains a multiplicity of elements.

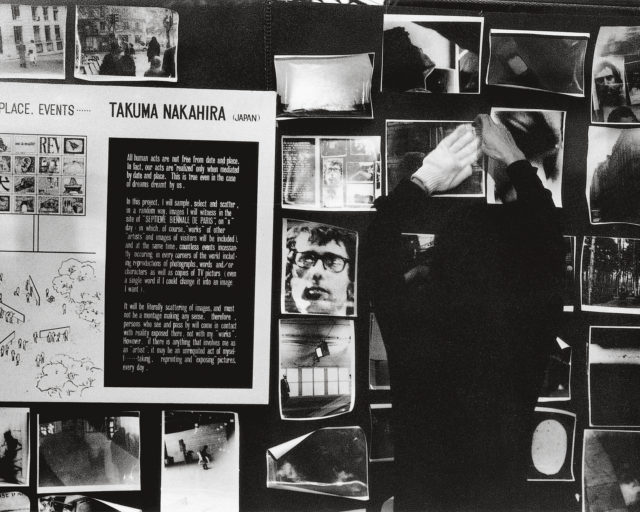

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and Courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Vartanian: In your early magazine work, your photographs are often accompanied by texts you’ve written in an “editorial voice” of sorts.

Moriyama: When I was young, I used to write accompanying texts for my images. Those writings had something of a didactic relationship with the images. In the end, the language with which the viewer sees the photograph changes the image’s content. Even if I chose a word or language with which to take an image, it would be impossible to have everyone feel the same way. Perhaps by chance, a viewer may have a similar feeling.

In working with my older photographs, I treat them as if they are something new—if I didn’t, presenting older work would be pointless. What I photographed at a certain point may have been vivid at the time, but with the passage of years, its luster weathers with it. All work is subject to format, ways of looking, editorial style—all of which influence and alter the work. That process of alteration is one of the things I love about photography. In essence, through the process of recomposing the work, the photograph is revitalized as something that is contemporary—now. This can be done countless times with any image. In a way, this is like saying that within each image, there is a multitude of possibilities. A single photograph contains different images.

I happen to have produced many books of photographs. I work with others on them—people I trust to a certain extent—and I leave it to them to do the recomposition (as, for example, with Shashin yo, Sayonara [Farewell Photography, 1972]). The work becomes more vivid than when I do it myself. If I do it myself, I cannot avoid being influenced by memory; I strain to stave off that impulse and inadvertently create a palpable tension—and the outcome is often odd! Whereas when I work with a third party—or even someone more removed—filtering the images through their eyes, the photographs come alive, I think. Photographs that I’ve taken ten years ago even now seem vivid. If an image is good, it is brought back to life by the feelings of the viewer.

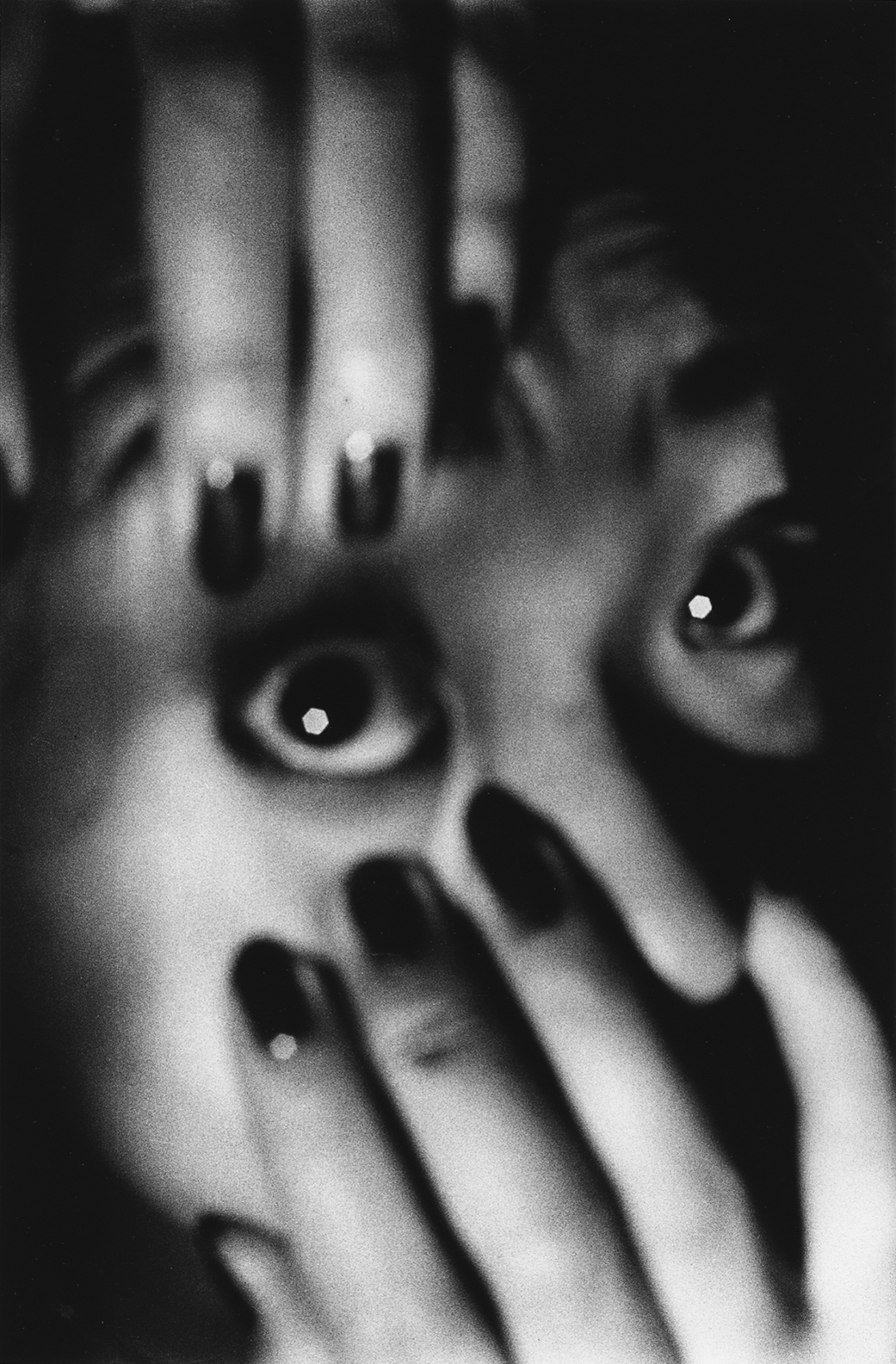

Courtesy The Walther Collection

Vartanian: What about the function of the photograph as information? Your work, especially from the 1970s, has so much to do with destabilizing this aspect of photography.

Moriyama: Photographs of any generation are in a basic sense, at that moment, information. Photography is underpinned by information. No matter how conceptual a photograph may be, it contains information at its most fundamental level. But the means by which information is communicated is specific to each generation. A recently shot photograph is just as viable to me as one shot ten years ago.

Vartanian: Do you make a distinction between the different media in which your work appears—magazines and books, exhibitions?

Moriyama: I don’t generally make a distinction between them. A magazine has a particular objective, namely it is about the now. In that sense, it uses the information aspect of photographs. And depending on the editorial direction, the photographs may radically change. So if the editorial direction of a particular magazine doesn’t sit well with me, I don’t allow my photographs to be used in it. But in principle, whether a photograph is framed and mounted as part of an exhibition or shown in a photobook or magazine—these are just different modalities of the same image. Each is interesting in its way. For that reason, I don’t place a lower ranking on magazines. At times, in fact, the magazine reproduction has been the best format for an image, trumping other forms. Again, what interests me is seeing my photographs in a manner that makes them seem different. And in the magazine context, if the photograph doesn’t come alive, it doesn’t necessarily mean there was something wrong with the editorial direction; it probably means the photographs aren’t that strong. There are two sides of a coin.

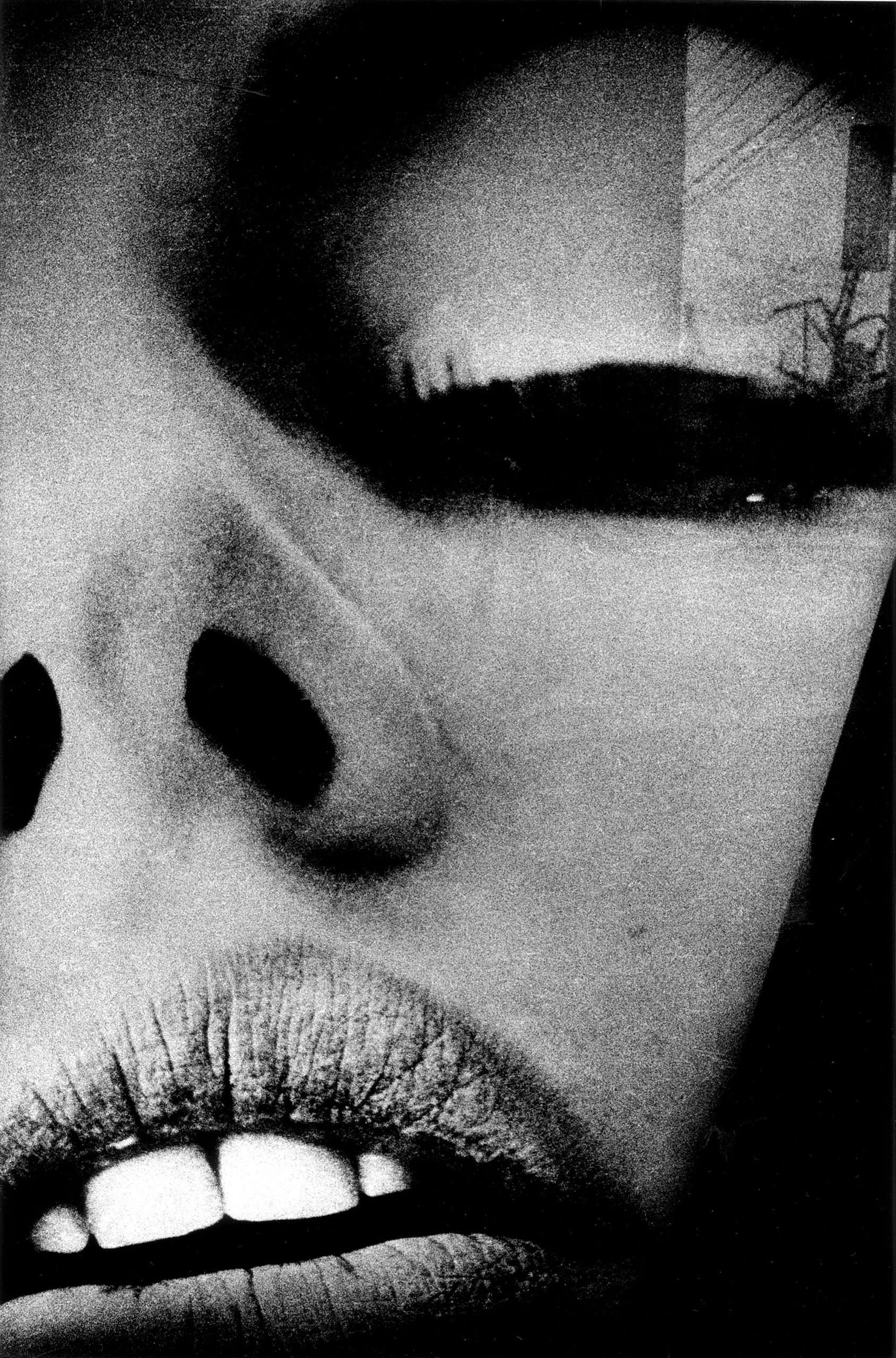

Courtesy Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and Akio Nagasawa Gallery

Vartanian: Your work is largely black and white. How do you think of color in relation to black-and-white work?

Moriyama: There isn’t much difference between photographing in color or black and white. I am someone who has been making black-and-white photographs forever— and to be honest I still prefer black and white. But part of what makes color photography interesting to me are digital cameras. With film cameras, your choice is made once the film is loaded. With digital, on the other hand, something that is shot in color can be converted to black and white. So for the time being I am shooting in color.

Monochromatic photography is conventionally thought of as having more symbolic, abstract, dreamlike qualities. But I don’t necessarily think that just because an image is in color it is closer to reality. Recently, many people have been asking me why I’m photographing in color. It is tantamount to asking me why I am using digital to shoot. What difference does it make? Particularly outside of Japan, there is an eagerness to have a clear-cut reason behind every choice, I find. (The same goes for explanations about the images themselves.) But there isn’t any real need to provide these answers. Making a definitive declaration of intent or meaning kills the photograph. Whether I want to print something in color or make it black and white all has to do with what I am feeling at the time.

Photographs that I’ve taken ten years ago even now seem vivid. If an image is good, it is brought back to life by the feelings of the viewer.

One distinction I can make—I’ve written about this in my essays: black-and- white photography has an erotic edge for me, in a broad sense. Color doesn’t have that same erotic charge. It doesn’t have so much to do with what is being photographed; in any black-and-white image there is some variety of eroticism.If I am out wandering and I see photographs hung on the walls of a restaurant, say, if they are black and white, I get a rush! It’s really a visceral response. I haven’t yet seen a color photograph that has given me shivers. That is the difference between the two.

But my interest in color is increasing. Sometimes when I see one of my black-and-white photographs, I think to myself: “That’s a Daido Moriyama image.” Whereas color work seems wholly different to me—still, there is something good about it. So what interests me is seeing my own work differently: the new, vague feeling of accepting the color work as my own. That is where I am now. At that vague, flickering stage.

Vartanian: There is a tendency now to think of photography in terms of themes or concepts.

Moriyama: There are no themes in my work. It may be difficult for this to be understood outside of Japan—and indeed, often my work is understood as having a theme. Even if I were to construct a theme (and it’s not as if I’ve never done so), I can’t really think about it as I’m working. It is too limiting, and the camera work becomes restricted. Within that constraint the photograph becomes a fabricated image, and for me that is meaningless. The work I am shooting now is being done in Tokyo, but I don’t necessarily think of it as having a theme that is “Tokyo.” With a predetermined theme, possibilities are reduced, and the conversation then becomes one of form. That’s not something that I am capable of doing, really.

Courtesy Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation and Akio Nagasawa Gallery

Vartanian: Many of your early writings about your photography discussed the sensation of taking photographs, which you often describe sometimes as “haziness” but mostly as a sort of “stimulation.” Has this changed for you? What’s the sensation of taking photographs now?

Moriyama: Nothing is really different. The passing decades change how we see—but basically I have always been shooting for exactly the same reason. The shock that comes from the outside world. That’s why imposing a theme drains photography of its spark. The outside world is extremely fluid and mixed up. Wrestling it into a “theme” is an impossibility. That mix in its totality cannot be photographed. Within a thin sliver of this world, only the thinnest of segments can be recorded with the photograph—but I keep photographing. There is nothing else.

With conceptual photography or with a prescribed theme, it is more or less apparent if the photograph is a success or not. When the object of the photograph is the city, it’s far from clear whether the photograph is working.

In one way, it is a very naive way of thinking. But to shoot images is to receive shocks from the outside world. I don’t maintain that awareness for extended periods while shooting, but through the outside world my own consciousness changes.

So, in relation to the city, I face the world and with this tiny camera I take photographs. Whatever the city—not only Tokyo—it is suffused with art; it is overflowing with the stuff. With that, I get a jolt of adrenaline. Once you experience that actuality you are unable to take any other kind of photographs.

Having said that, there are also instances when I work with assigned subjects, like the photographs I am taking now at the University Museum at the University of Tokyo. It’s not a subject I chose myself but it is interesting to me. Looking for the bizarre and fantastic within that cordoned-off area intrigues me—partly precisely because I don’t usually take photographs like this. Say I am asked to photograph a singer; my camera work really isn’t well suited for such work, but somewhere in the course of making the image, it becomes interesting. And from that session, one of the shots might make it into my printed work, and it is then entirely detached from its original meaning. There are no hard and fast rules with what and how I shoot.

It may seem strange to say, but I believe in the outside world of the city more than I believe in myself. I think it is through it that change happens. I have been this way since I was young. Feeling the world to be a threat. It’s a continual anxiety— but there’s nothing to be done about it. There are times when I am by myself at home at night, and I start thinking about the city’s Shinjuku area at night, and how interesting it must be—it becomes difficult for me to sit still.

Photography never reaches a state of completion. That is what makes it interesting—amazing. When I was young I made projects like Farewell Photography. It was all fiction. Although, for me at that time, it was a form of reality. It was excessive. Pop, cheap junk, scandal, accident, somewhere in the day-in-day-out, there is something extraordinary. There is a ton of it. That is what I am interested in. That is what I respond to.

This interview was originally published in Aperture, issue 203, Summer 2011, and anthologized in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018). Translated from the Japanese by Ivan Vartanian.