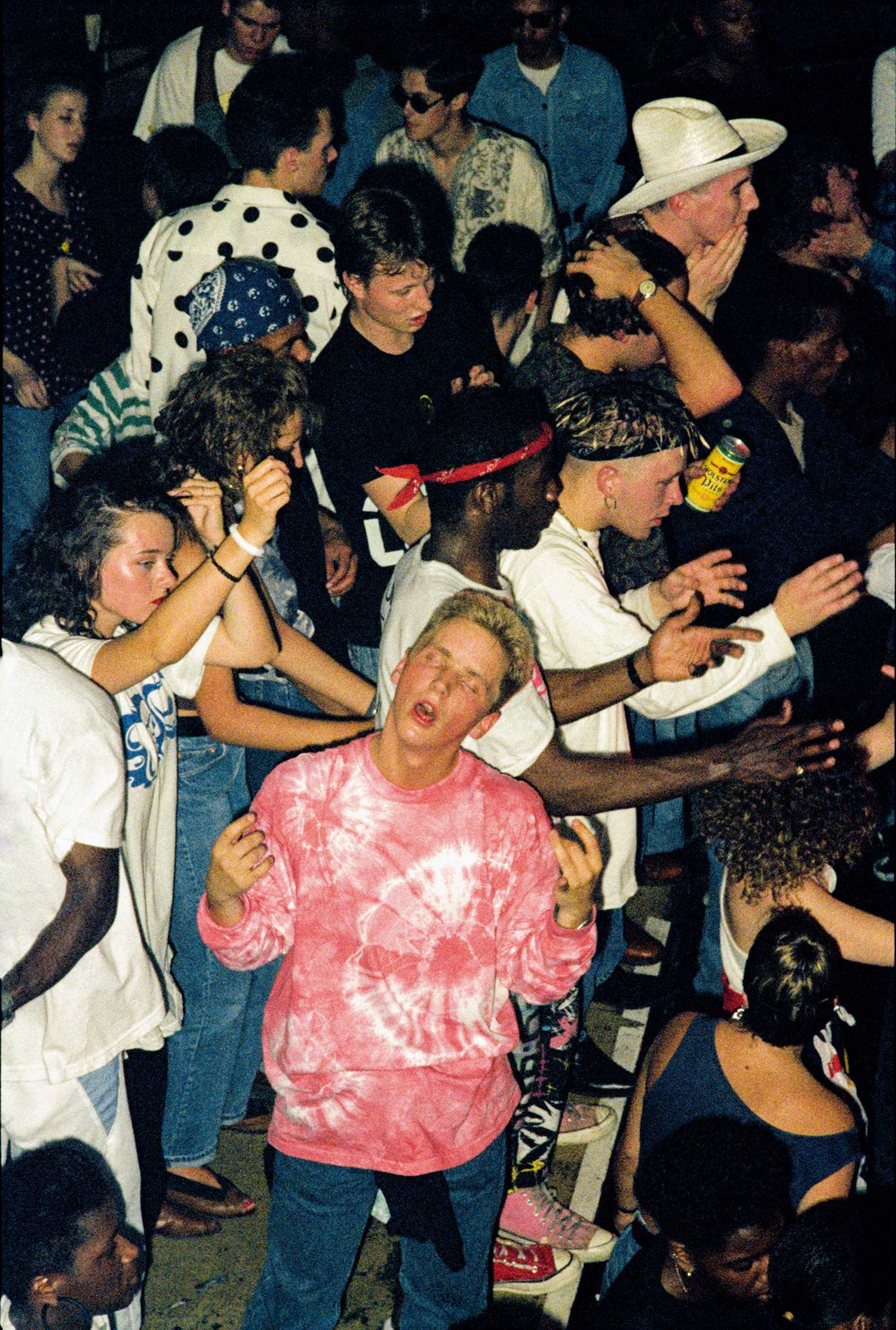

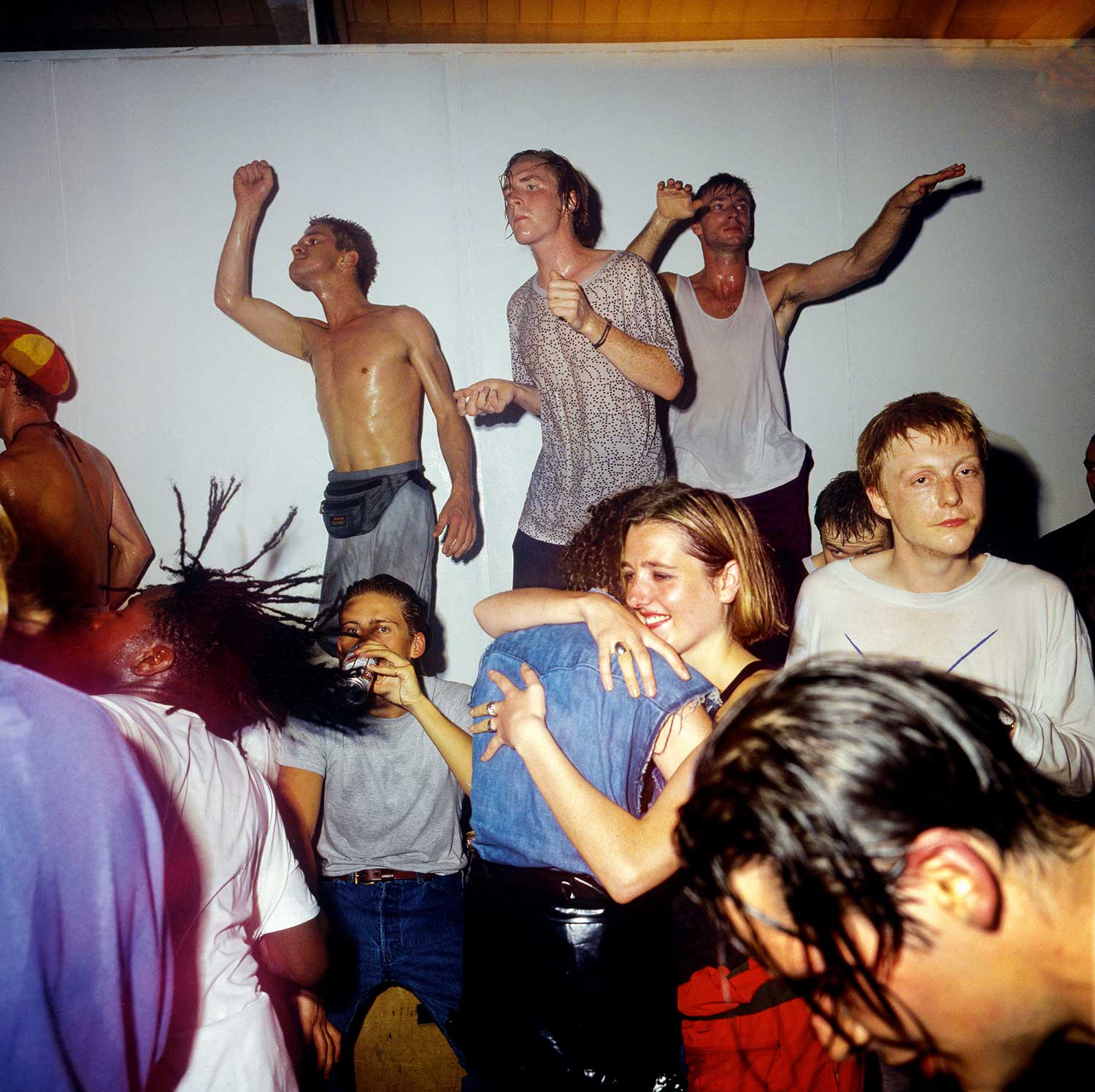

Dave Swindells, Podium dancers at the Trip, the Astoria, Soho, 1988

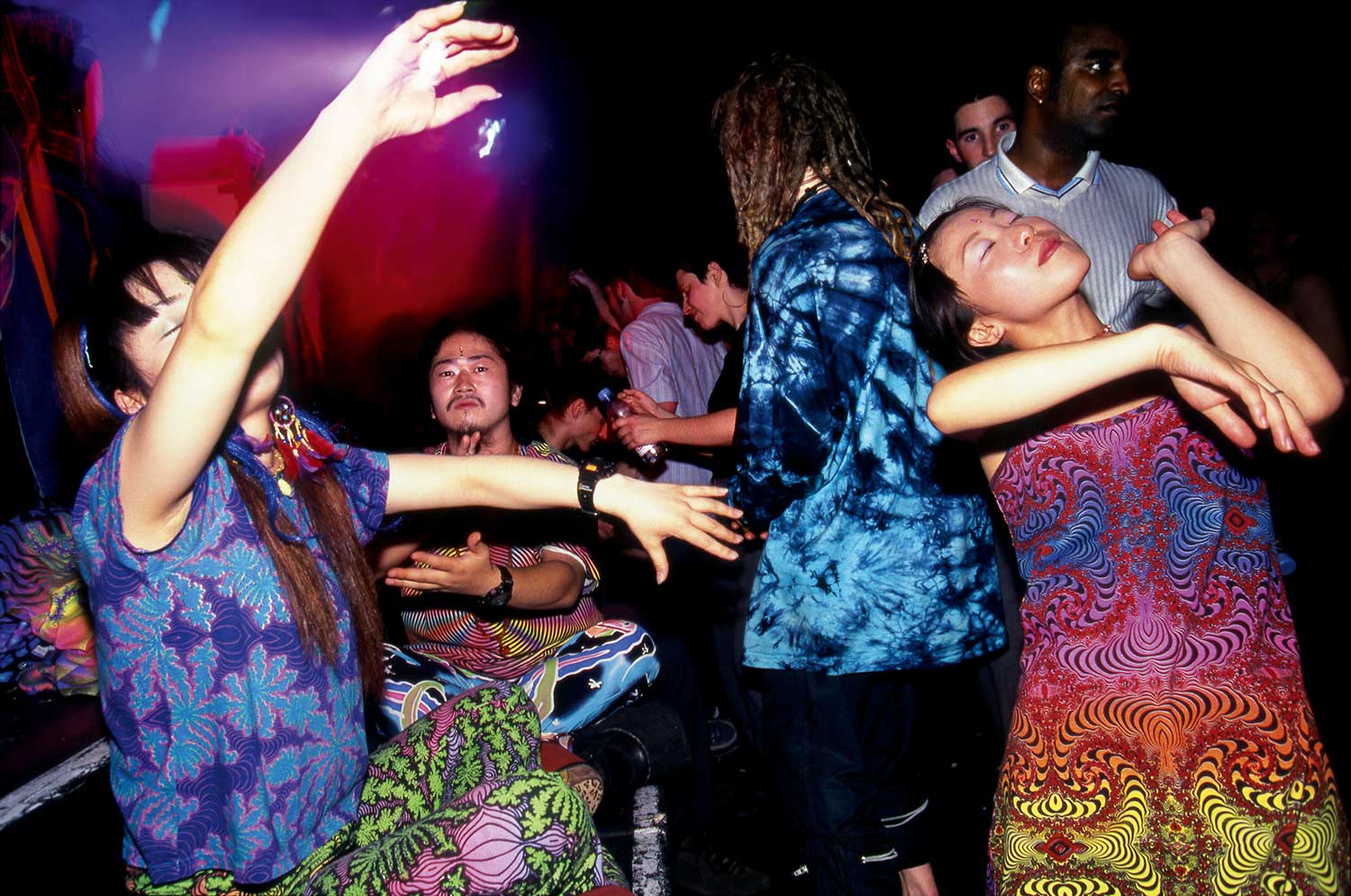

This is the British DJ Danny Rampling talking about the atmosphere in the early days of his nightclub Shoom, in 1988 London, at the start of the acid-house explosion that sent shock waves through U.K. youth culture, and eventually worldwide: “It was very spiritual. Some of those moments in the club were unbelievable. People literally went into trance states, including me. Not from the use of drugs, but from that music and the human energy that was going around [the room]. That’s not something that had happened in Britain for centuries. The feeling in that small space was so intense some nights.”

And this is the photographer Dave Swindells talking about that same club: “It was really hot, sweaty and steamy. There was dry ice, strobe lights going off and you’re thinking, ‘I’ve got to wait half an hour for the camera to warm up.’ You can’t use it until it’s at room temperature, because otherwise it’s just going to be fogged the whole time, and you’re not going to see anything. In Shoom, you could barely see the length of your arm sometimes, so it was a challenge! But it was also something you’d not seen before, so you just had to capture it.”

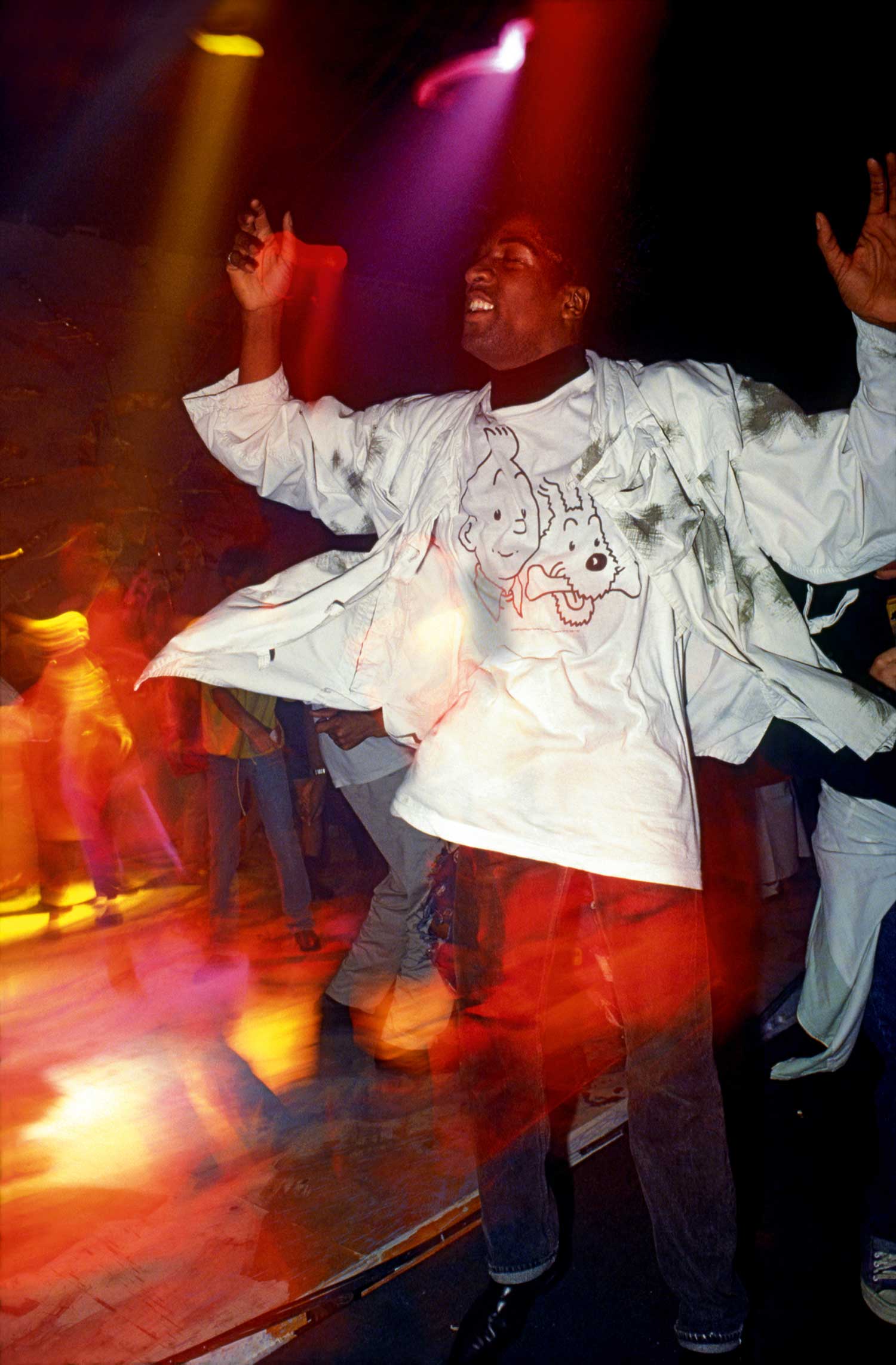

At their best, nightclubs have always functioned as what the anarchist writer Hakim Bey calls “temporary autonomous zones”––safe spaces where we can experiment, express ourselves, and explore freedoms we may not be allowed in daily life. In clubs, we can find our tribe, feel a real sense of belonging and community. They are also often at the forefront of social change, encouraging racial integration and asserting gay rights. In the case of acid house, overwhelming numbers of clubgoers defying the police to dance all night at huge, illegal parties eventually led––after new laws failed to contain them––to a gradual loosening of the draconian restrictions on both club opening hours and the sale and consumption of alcohol in the U.K.

These characteristics have also made the nightlife scene hard to record. There are technical issues for photographers in clubs, but also issues of trust. Swindells has been able to take candid pictures in clubs like Shoom because he made himself part of the culture by turning up night after night, year after year, bearing witness without ever being intrusive.

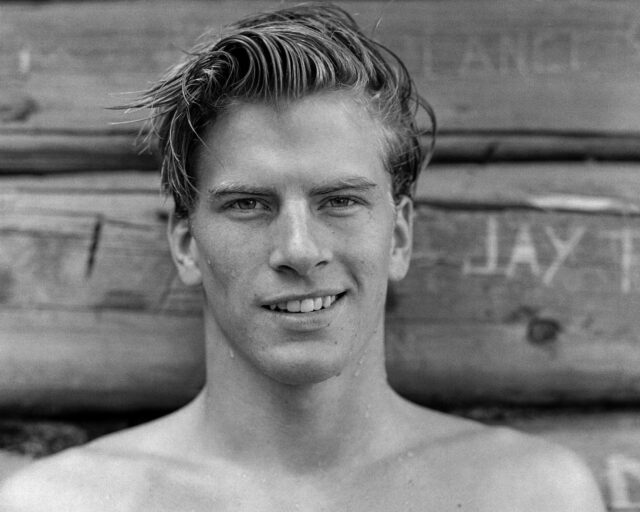

Swindells started taking photographs while at university in Sheffield, inspired by a 1982 exhibition of Derek Ridgers’s nightclub portraits at the Photographers’ Gallery in London. After graduating, he moved to London and got a bar job in a club––until he was fired for spending too much time taking pictures and not enough time collecting empty glasses. In 1985, he started taking club portraits for the style bible i-D, then became nightlife editor of Time Out. Going out with his camera almost every evening, he remained at the magazine from September 1986 to January 2009, building up an unsurpassed archive on British club culture.

“Taking pictures definitely kept me going, because you had to keep on interacting with the people on the dance floor, and not just the DJ and the promoter, or hang out in the VIP room. You get detached from it all that way. And when electroclash and Nu Rave came along in the noughties, they reinspired me. It was 1980s clubbers re-creating ’80s nightlife, so those things were a lot of fun.”

The Internet has given us new ways of finding our tribe, but Swindells says that feeling of togetherness, of being part of something bigger than yourself, can still be found in the clubs on a good night. What is different now is that clubbers are more aware of his presence, often wanting to see the pictures and edit them on the spot. “They’re used to having control of their image, their brand, so they want to be much more involved. Which is fair enough. But what hasn’t changed is the joy on people’s faces when the DJ plays a tune they love, that sense of just pure joy. There’s still a massive buzz that people feel.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from Aperture issue 237, “Spirituality.”