Let Us Now Praise David Lebe

David Lebe, Angelo on the Roof, 1979

In 2017, Peter Barberie, Curator of Photographs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, extended a somewhat cryptic invitation to me. “I’m working on an exhibition with a little-known photographer named David Lebe, whose work I love,” he wrote. “I would like to show you.”

A few weeks later I hunched tentatively off the train from New York and found my way to the museum, where, leaning seductively on mahogany shelves in a viewing room for works on paper, I discovered David Lebe’s hand-colored gelatin-silver print Seth (1985). It alone was worth the trip. The delicately wrought tones of Seth, its large format, and the intricacy of its analog compositing all make for an example of photographic ingenuity that would be considered momentous by any standard.

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Seth turned out to be just the beginning. Relatively few people knew about Lebe until this year, when the Philadelphia Museum of Art opened the career survey Long Light: Photographs by David Lebe. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue attempt to complicate the narrow canon of gay photography of the 1970s and ’80s on an institutional level by forging new space for a septuagenarian artist and his rich and varied body of work.

“A lot of queer artists in the 1970s and ’80s turned to photography as their medium of choice,” Barberie said. “That is a story that is still being told, it’s still unfolding, and there are many voices who are part of that story. This exhibition is just one iteration.” Barberie was speaking to a standing-room-only crowd gathered one afternoon in February to hear a public conversation with Lebe soon after the exhibition’s opening. “One of my goals for this exhibition, and I think the most important one, is to give support and space to this tremendously moving body of work. But I also want to make a contribution to our understanding of queer art during these crucial decades.”

David Lebe was a fixture of the Philadelphia art scene in the 1970s, and his center-city home on South Fifteenth Street was a gathering place for friends, students, and others involved in the arts. He studied with Ray K. Metzker and Barbara Blondeau and was a close friend and roommate of the artist Barbara Crane; the Bauhaus-y ethos of experimentation handed down from Moholy-Nagy at Chicago’s Institute of Design—of pushing mundane circumstances past their furthest logical conclusion—can be felt in every part of Lebe’s work.

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Lebe was known for developing a certain kind of “light drawing” that melded details of the real world and male bodies with gestural marks drawn in with a pen light during long exposures. Some of these images are in the Philadelphia Museum’s collection, and they were Barberie’s introduction to Lebe’s work. They were also the primary focus of perhaps the only other comprehensive exhibition of Lebe’s work, a show called Truth Fantasy, which was staged in 1986 by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and accompanied by a small, staple-bound catalogue. In his essay for that publication, curator Tom Beck writes, “Autobiography is the key to [Lebe’s] work, which has shifted from time to time among photograms, light drawings, and male nudes.” Beck adds, in a seemingly personal note amid otherwise dry curatorial text, “Until the age of 25, David Lebe lived a closeted life; his life was about keeping a secret. Finally, he vowed to be open and honest about his homoerotic personal and aesthetic life.”

When Lebe discovered he had AIDS in the late 1980s, the diagnosis would almost have amounted to a death sentence. Soon after finding out, he met Jack Potter, who also has AIDS, and they fell in love. Though their lives were in Philadelphia, they withdrew to upstate New York, a decision they made in an attempt to improve their fragile immune systems. They moved to an area that has been cultivated since the mid-twentieth century by Anthroposophists, members of a philosophical organization whose adherents follow, to varying degrees, the teachings of the Austrian-born philosopher Rudolf Steiner. Anthroposophy promotes holistic living and Steiner made advancements in biodynamic farming, so the community uniquely provides a wide range of the organic crops Lebe and Potter need for their macrobiotic diet. “Jack came very close to dying, and David also declined, but amazingly they rallied with new drug combinations that became available after 1995,” Barberie writes in the catalogue. Today they are remarkably healthy and full of zeal and appreciation for life, though they face a range of physical challenges that mean, among other things, that they spend most of their time at home.

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

In November 2017, I took a train and then a cab to Lebe and Potter’s home near Ghent, New York, to see more of Lebe’s work in person. Everything in their house and their life together was organized just so, as if the house were an artwork. Rooms had been painted and repainted many times over to match or contrast the landscape perfectly, as well as the particular character of light and the objects and artworks inside.

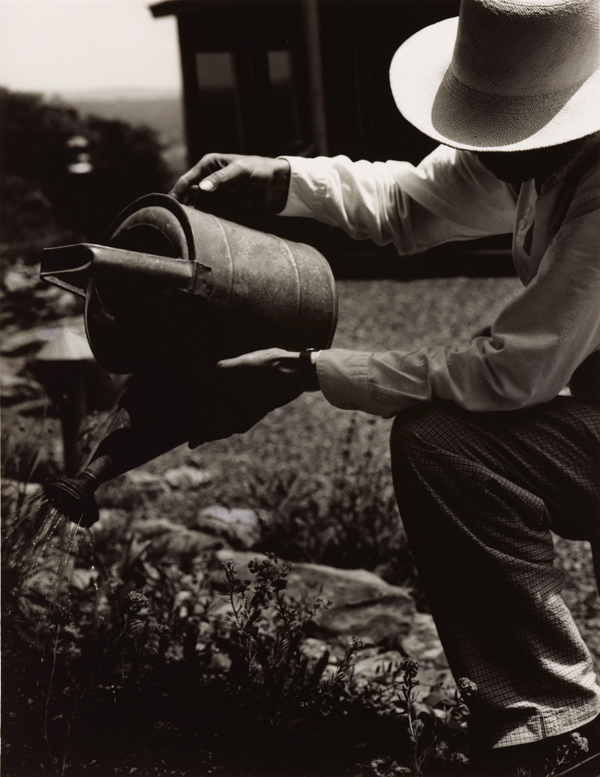

We toured Potter’s garden, which was past its prime after a cold spell the week before, but purple flowers still blossomed on a few bushes near the ground. (He commented that they were bracts rather than flowers. Bracts, I later learned, are ornamental or colorful leaves that protect a smaller, more fragile bloom within, which I guess was the reason they survived the freeze.) We went inside, and I looked at prints with Lebe in an immaculate attic studio as Potter prepared dinner: mixed whole grains topped with natto, a traditional Japanese dish that he’d made himself by fermenting soy beans, a food they’d come to early in their macrobiotic diet.

Up in the attic, I experienced a second, slower revelation than I had in the museum’s viewing room. I began by looking at Lebe’s hand-colored botanical photographs, which are a technical marvel. The exact combination of spliced, projected negatives, contacted photogram objects, and hand coloring that was required to make these pieces in the darkroom is mystifying. The works are surreal in their spare landscapes and gradient skies, lost children of the psychologically inflected figurative paintings Jared French made in the mid-twentieth century and the botanical photograms of Anna Atkins a hundred years before.

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

I also leafed through an album of pictures from the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, in 1987. Lebe made the pictures using high-speed recording film, a black-and-white process known for its usefulness in low light and its unpredictability in terms of grain. Four-by-six prints were arranged in a modestly sized album, with the names of the people in the pictures written underneath in ballpoint pen. Lebe told me this was the first LGBT march on Washington where AIDS was a part of the agenda, but when I looked at the faces of the people in the photographs what I saw was joy instead of fear or anguish.

Barberie, too, feels these early works are essential to Lebe’s message. “Lebe discovered he had AIDS soon after the march,” he writes. “Over the decade that followed, he produced diverse photographs that grapple with the disease and its impact, and which together form the crucial part of his artistic achievement.”

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

It wasn’t until the current exhibition, however, that I saw one of the central pieces in Lebe’s work, a series called Morning Ritual (1994), made after he and Potter moved to the mountains. These smallish, black-and-white pictures exude tenderness through gestures of caring and intimacy, but also make the daily routines of the couple, whose health was still extremely perilous, into little photographic gifts of fine tonality and formal invention. If photography is often an honorific form, these pictures honor the quietest moments in Lebe’s life. They appear to genuflect for these times, and as part of a daily practice also mark time as it passes. They insist delicately, day by day, We are still here.

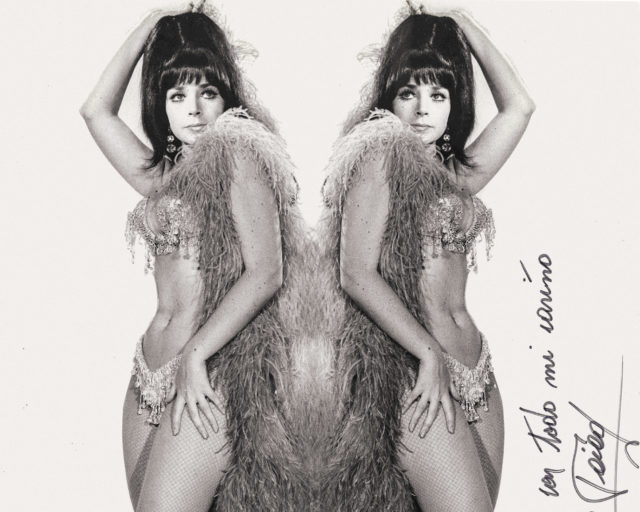

Robert Mapplethorpe, the go-to gay photographer of all time, naturally comes up in comparison to Lebe’s work and the culture of the 1980s. Lebe photographs flowers in black and white, and also deals with the erotic male body, sometimes explicitly. This is the case in a series of photographs of the porn star, activist, and writer Scott O’Hara, a friend and muse who Lebe photographed, often masturbating, in a series of four sittings between 1989 and 1996. During these years, pornography took on a new importance for gay men as a means of safe sex, free from the existential anxieties a hookup might incur. Of his photos of O’Hara, Lebe wrote, in 2013, “They are about, in part, the refusal to give up on life or on life’s pleasures. A triumph of spirit over AIDS.”

© the artist and courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art originated Mapplethorpe’s infamous 1988–89 retrospective that later went on to upset conservatives throughout the United States. Lebe saw the exhibition—and even appears in the 2016 HBO documentary Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures examining Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio, which was installed at the ICA in a glass case built purposefully too high so as to prevent children from seeing the images. In February, during their conversation, Barberie asked Lebe what his reaction to the show had been. “I was doing male nude work at the same time he was, and so it wasn’t as if I saw his work and thought, Oh, it’s OK to do that. I was already doing that. It’s just that nobody saw it like they saw his work,” Lebe said. “I wasn’t searching out people who I thought would make startling or interesting photographs. My inspiration for photography always came from my life and myself.” Lebe recalled seeing the work of Minor White and Duane Michals, but not being certain if they were gay. “And that was frustrating and annoying,” he said. “So from an early time I just decided to be open in my work, and just let people know that I was gay and that the work came from that experience.”

All too often, museums and galleries show overexposed work by already famous artists, the ones who have been affirmed in the history of photography, like the recent museum and gallery exhibitions of Stephen Shore and William Eggleston in New York, or the Guggenheim’s two-part yearlong Mapplethorpe show. This is precisely why Lebe’s career-spanning retrospective being staged at a major museum is essential. Lebe is now incontrovertibly part of the history of twentieth-century queer artists. Given the number of voices silenced by HIV and AIDS, it is crucial to look back and celebrate the important work that queer artists made despite personal and political adversity. As a gay artist born in the late 1980s, at the height of fear about the American AIDS crisis, the trauma of the previous generation looms like a kind of silence of arrested potential. We can still hear that silence, and we could use more saints.

Long Light: Photographs by David Lebe is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through May 5, 2019.