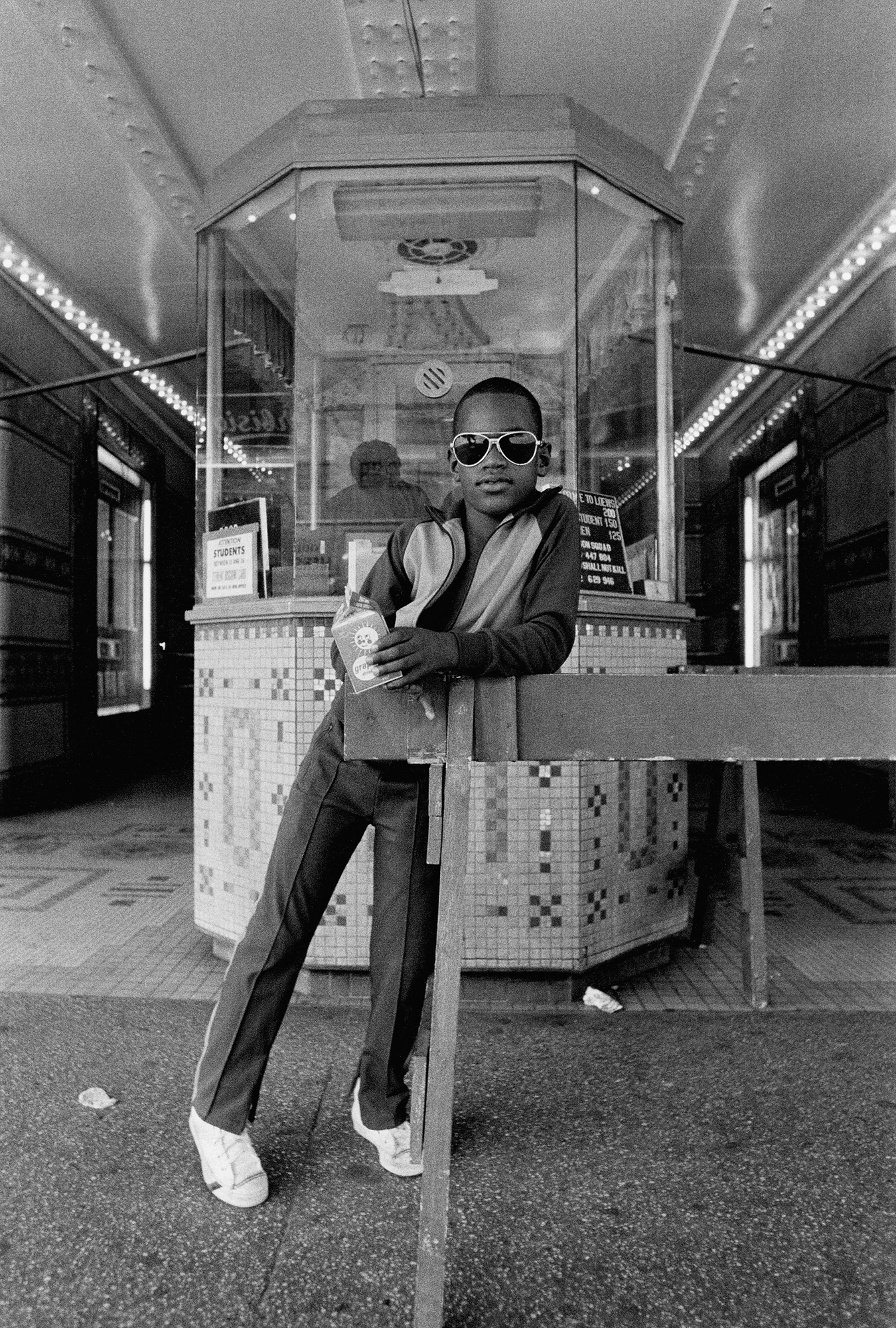

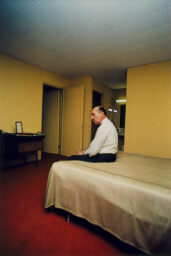

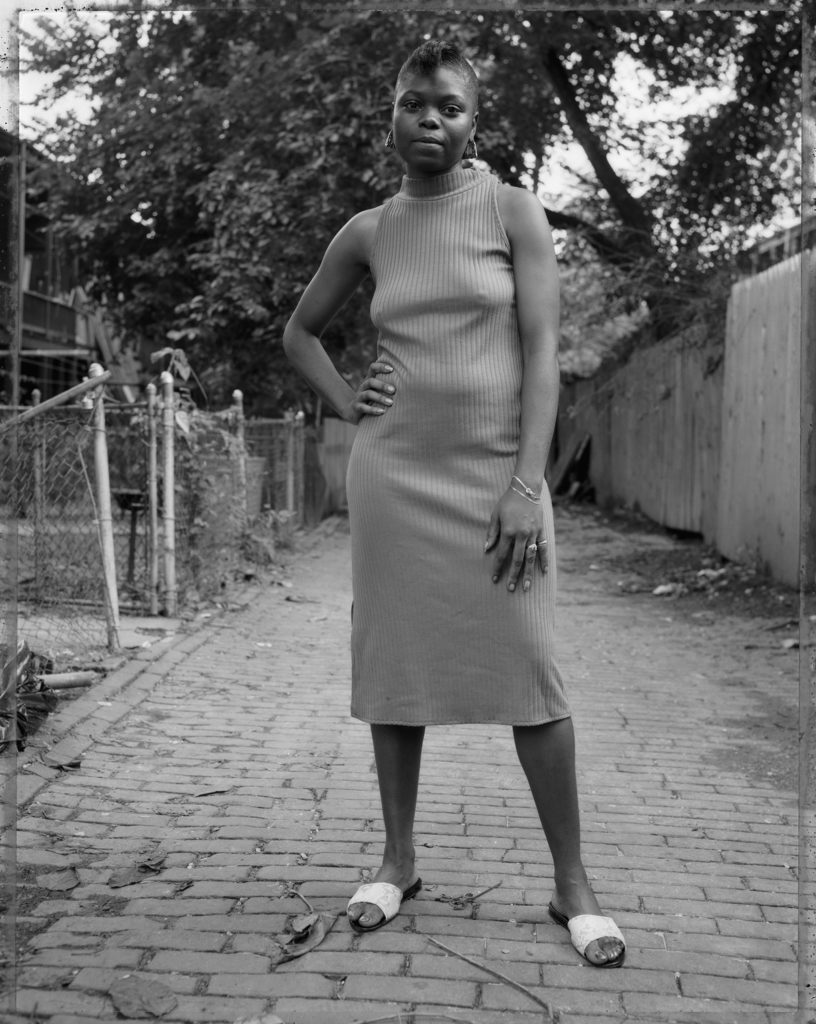

Dawoud Bey, A Boy in Front of the Loew’s 125th Street Movie Theatre, Harlem, 1976

Dawoud Bey is one of the most influential photographers of his generation. The subject of a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, scheduled for April 2021, and a new monograph to be published by MACK, Bey began his career in New York in the 1970s, making evocative portraits in Harlem and Brooklyn. In the context of the Aperture Forward winter campaign, Bey spoke with Chris Boot, who is approaching the end of a ten-year term as executive director of Aperture Foundation, about the changes in the world of photography over the decade since the rise of Instagram and the iPhone.

Chris Boot: Dawoud, I’m writing you on November 8, thirty hours or so after Joe Biden and Kamala Harris declared victory in the U.S. elections. It’s been an amazing couple of days; there has been such an explosion of joy and relief during these sublime, warm fall days here on the East Coast. I will never forget how yesterday and today felt. This is very British of me to ask, but how is the weather in Chicago? Is it all joy there too?

Dawoud Bey: Having this conversation at this moment feels like when the reset button has been hit, and just in the nick of time! With the pandemic now going into its ninth month unabated, and with no structure in place to mitigate it, it was feeling like an endless march over a cliff. Fortunately, that reign of gratuitous horror has come to an end, though there will be much work ahead—and the lingering fact that almost half the country voted to continue down that path to contend with.

It has been relatively balmy here in Chicago for this time of the year, with temperatures in the high sixties to mid-seventies, and the sun seemed to be shining just a little brighter after the election results came in. Folks were dancing in the streets in every neighborhood except one in Chicago, with forty-nine of fifty wards going for Biden. And of course, having Kamala Harris as the first Black vice president–elect brings an extraordinary air of expectation and possibility back to the country. So, things are good here for the moment, and we should all enjoy it, before getting back to the work of making the democratic project work for everyone.

Boot: Photography has always been dynamic, continuing to reinvent itself, artistically and in terms of its social role. Given the events of this year, do you think that 2020 might turn out to be a particular moment of transformation in our field and its story?

Bey: When I think about how to answer that, I think about the two primary ways in which I engage with photography, through my own practice as an artist and through teaching, both of which I’ve been engaged in for over four decades. My own practice is rooted in the moment that I came to photography, which goes back to the 1970s, when I started going out to look at photographs in an art context for the first time. And at that time, that meant going to see the work of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon at Marlborough Gallery, and encountering the photographs of Mike Disfarmer in a small exhibition at MoMA. I happened upon a Harry Callahan exhibition at the Met around the same time. I had previously encountered Roy DeCarava’s photographs in a copy of The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), but hadn’t yet seen those pictures on a wall, so their full impact hadn’t yet hit me, though they were on my radar.

I found all of these exhibitions by scouring the New York Times exhibition listings on Sundays, when my dad brought home the Sunday paper. I have no idea how I would have found this information otherwise. Exhibitions of photographs were not even ubiquitous at that time, so there were never more than two or three exhibitions listed on any given week. And as a very young Black man, I was acutely aware that I never encountered another Black person in any of the spaces where I was seeing these photographs.

Boot: What has changed since then?

Bey: Well, fast-forward to my young students today and the ways they both find out about photographers and how they make their own pictures visible in the world. Inevitably, it’s through the use of the computer or their phones, through Instagram and whatever other platforms they are looking at and using. For the most part, they never even see these pictures in the physical form of an actual photographic print. With the millions of photographs being posted on Instagram, I don’t even know how you find a particular photographer that you find interesting in that glut of online images.

My son works in the music industry, and he routinely finds artists and photographers that he wants to work with for different projects on Instagram. Again, I’m mystified as to how one navigates that platform with intention. So that’s one huge difference that I’m seeing. And yes, I do have my own IG page. Funny thing is, the first time I posted a picture on it, I got a text from my son in a matter of minutes telling me, “take it down . . . now!” Apparently, I was posting the “wrong” kind of picture on the page, and not using it the “right” way. I had to have my son—who is twenty-nine now—break down for me how I should be using Instagram and the relationship between IG and other social-media platforms. He lives and works in that space every day, so I never questioned his advice.

At this moment of the pandemic and online teaching, I’m teaching students online who are making work that I will likely never see physically, and—from what they tell me—will never exist as physical prints anyway. As much as I thought I was going to absolutely hate teaching online, I’m actually getting comfortable with it. Of course, one of the reasons I teach is to be able to remain current and have a conversation with what a younger generation of photographers are doing, and how they are thinking about their work and the field. They are still passionate about visualizing the world in pictures—which I now use as distinct from “photographs” which, to me, remain a description of a physical object—the world they are inhabiting, regardless of the tool.

Boot: It’s fascinating that your son guides you—a great photographer of our time—in how to communicate on Instagram!

Bey: Well, it makes sense. He’s more the demographic for users of IG than I am. And in his case, as a director of online and social-media content at a major label, he works in social media for a Iiving, so his understanding of it is infinitely more sharply honed than mine. I suspect that my peers who are my age (who are photographers or “art and culture workers”) make up a less than a tiny percentage of the over one billion users in the IG space.

Boot: I feel like, as a result of the rise of the iPhone, above all, the beginning of the 2010s was characterized in our field by the question: what is photography now, what is it becoming? I recall the sense of opportunity for photography, above all, but it was threatening too. The question became a thread at Aperture, while we tried to understand this new landscape. We explored it with projects like the issue we used to launch the new design of Aperture magazine, “Hello, Photography” (Spring 2013), an optimistic assertion of the value of photography; the Aperture magazine issue we did with Magnum Foundation, “Documentary, Expanded” (Spring 2014); and Charlotte Cotton’s book Photography Is Magic (2015), among others. I think Photography Is Magic was the apotheosis of a distinct ontological moment in photography.

Bey: It’s an interesting issue, because the present never completely supplants the past, it drives it in unanticipated directions; like, history doesn’t implode, it expands. The “Hello, Photography” issue of Aperture magazine, for all of its heralding of a new moment of just what constituted photography, kind of hedged its bets with the inclusion of some decidedly conventional work (by Garry Winogrand, for example, and a few others), in addition to work that did begin to really reshape the picture-making discourse—formally, conceptually, and materially.

I still recall the uproar within the field in 2010 when Damon Winter’s iPhone pictures, made while he was embedded with troops in Afghanistan, appeared in the New York Times Magazine, setting off a debate about the veracity of the photographs, along with debates around the ethical use of the Hipstamatic app that Winter used with his iPhone. The field didn’t yet seem ready to accept the possibility of the iPhone as a serious picture-making tool. Those arguments seem quaint now, of course.

I think Photography Is Magic pushed the envelope even further by advancing work that, in some cases, challenged the notion of a photograph as a particular kind of material object. As an artist, I have to admit I was not always terribly interested in some of that work, but Aperture, long an important voice in the field, certainly did the necessary thing in trying to track these changes, and to help the photography-interested public make sense of these changes as they were taking place. It was also important to document this reshaping of the field and its expanding discourses on the printed and published page.

But we can look elsewhere, at that same historical moment, and find photographers setting up their tripods and loading film into their cameras to make work about that piece of the world that mattered to them, and making photographs that resonate for the viewer. So it’s a kind of elasticity, I think, that keeps expanding, without really snapping and losing its shape completely. One thing we do know is that, unlike other expressive mediums—say, painting, for instance—photography’s evolution has always been tied to the evolution of its particular technologies.

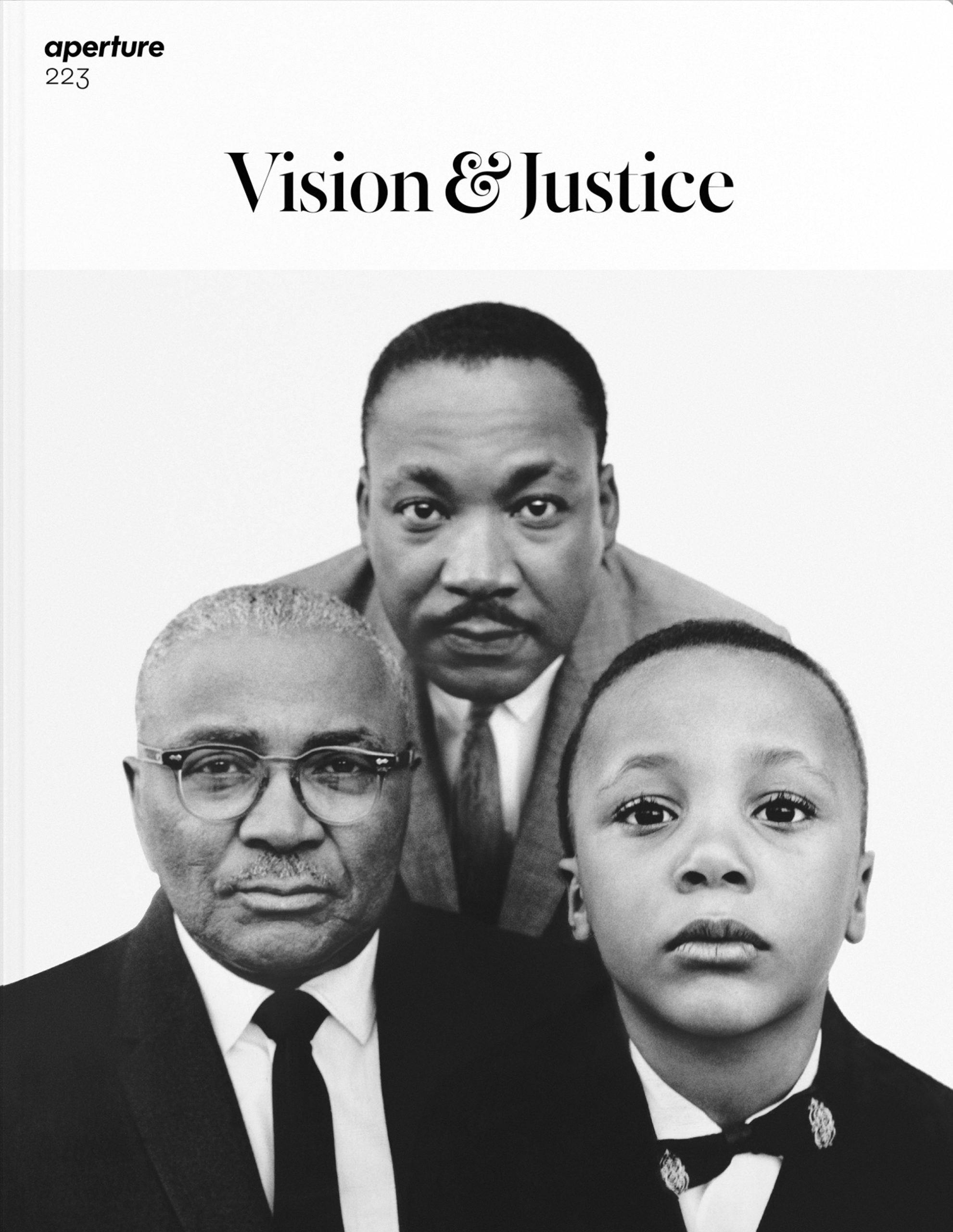

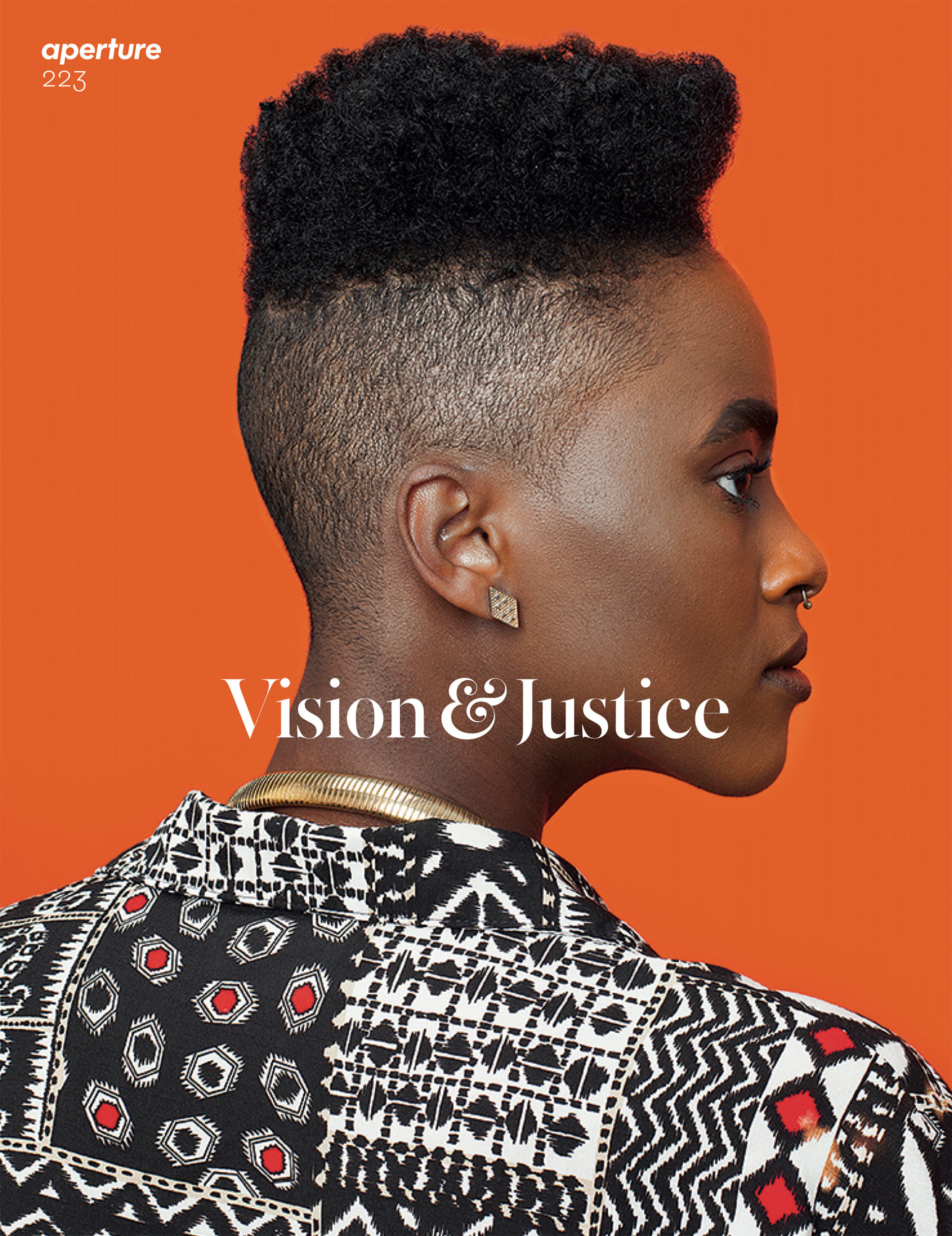

Boot: I remember thinking at Aperture, in the mid-2010s, Now we can see the new shape of photography, we don’t need to keep asking what it is. So, what next? This was around the time of the early Black Lives Matter demonstrations. And because photography was so central to them—Black Lives Matter mobilized via evidence of police killings caught on cell-phone cameras and distributed virally on social media—at Aperture, we felt we had some responsibility to speak to issues of inequality in the U.S. By then, Aperture magazine had published the “Queer” issue (Spring 2015), so we had already begun looking at the evolving role of photography in society, and inviting a more diverse group of authors to feature centrally into the story. But it was “Vision & Justice” (Summer 2016), guest-edited by Sarah Lewis—which includes selections from your Birmingham Project (2012–13)—that became the most conspicuous landmark in our own evolution. (The issue is now in its fourth printing.) That was the start of a journey, and there was never any going back.

Since then, we have made part of our purpose to serve as a platform for more diverse voices and their contributions to our social imagination. I know we are just a small corner of this, and I don’t want to be overdramatic about it, but it feels like the effect of Black Lives Matter on photography in America has been absolutely huge, perhaps as big an influence as the launch of the iPhone.

Bey: Well, the field has never been monolithic, so I think it depends on which segment of the field you’re looking at. Certainly, the fact that everyone who has a phone is now a producer of images has been hugely impactful, and has created a major cultural shift in the past two decades. And in the hands of citizens who are witnessing—or are sometimes the very victims of—police violence, it has created a means for exponentially amplifying this type of racist violence in conjunction with social media, since it is social media that allows these images to become visible, even ubiquitous.

I would say it goes both ways. Photography has had a huge impact on the Black Lives Matter movement as a mass mobilization tool, through which huge numbers of people can see these acts of violence against the Black body on their phone or computer screens. What really amplified the effects of that fact was the COVID-19 pandemic, which basically forced everyone into confined social isolation in a way that much of their interaction with the world was, in fact, taking place on social media. Under these circumstances, with few of the day-to-day distractions that normally crowd our lives, these images became magnified tenfold, first with the harassment of a Black birder, Christian Cooper, in Central Park, threatened by a white female citizen; quickly followed by the images of a white father and son in a pickup truck on the back roads of Georgia hunting down Ahmaud Arbery, a Black jogger, and then killing him while their friend, who followed in his own truck, filmed the entire incident for sport.

And then, finally, all of America got to see, on their screens while isolated at home, the images of George Floyd being killed in broad daylight, while a seventeen-year-old Black teenager, Darnella Frazier, filmed the footage on her phone. The extraordinary extent to which that brave young Black woman was able to stop, lift her phone, compose with a steady hand, and not flinch or shake, even as the police officer killing Floyd looked right into the lens of her phone suggests, to me, the ways in which people have been primed by the prevalence of images to be sophisticated producers of those images.

So, I think photography, and camera phones, has made people even more aware of the power of images which, in turn, has caused them to become more engaged producers, viewers, and responders to these images. The Black Lives Matter movement expanded exponentially during the pandemic, when that footage of Floyd’s killing was front and center on everyone’s screens in a way that was inextricable and undeniable. Frazier knew exactly how to make that footage go viral via social media. As a consequence, even more people—particularly non-Blacks—were forced to respond viscerally to these images by taking to the streets, demanding the police be held accountable and that Black Lives indeed do matter. So, yes, images are very much prevalent and much more catalytic to the Black Lives Matters movement.

Boot: Our interests coincided with the rise of new work and new attitudes—by Black, women, queer, and transgender photographers—taking photography by the scruff of the neck and giving it a good shake. It felt like a professional viewing class telling the stories of others was being displaced by photographers telling their own stories and shaping new identities in pictures. The energy of photography now is at that spot where great picture-making meets passionate argument around issues of representation and social justice.

Bey: I think Aperture and Aperture magazine have done very well in continuing to be an organization and publication that has a place in those foundational histories (as biased as they may have been), while also increasingly and forcefully remaking itself as a publication that is also reflective of the broader social conversations that have been taking place within various marginalized and excluded communities and populations, making the publication a place for a more representational kind of inclusion, as opposed to a more insular and exclusive platform for a particular kind of photographic practice.

Earlier publications may have included work about some of those communities, but through images that were seldom—if ever—made by those who are actually producing work from inside those populations. That has been a very important shift—that these communities are the producers and authors of work that reflects their experiences and are, in fact, the authors of their own cultures. The old model was usually that a white photographer, like Bruce Davidson (with East 100th Street, 1970) or Eugene Richards (with Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue, 1994), was the visual authorial voice of those Black and Brown communities. In an earlier time, Paul Strand photographed in Mexico and Ghana, without most people having a broader awareness that the African continent and Mexico also had their own rich traditions of photography.

It’s also important to note, in the more recent inclusion of diverse voices in Aperture magazine, that work coming out of those communities does not subscribe to any orthodoxy, that it is as conceptually rich and varied as work being produced anywhere else. In the end, Aperture magazine has become a platform for redefining the notion of image-making in a more inclusive America, and then placing that alongside a global conversation.

Boot: What does the arc of your career over the same period look like?

Bey: For me, as an artist working inside of the medium whose own work stems from my coming of age during the social tumult of the late 1960s, a lot of the issues that have again come to the forefront over this past decade have actually been present for a very long time. The year 2020, in a way, feels like 1969 redux. Only now, the struggle around these issues of institutional access, police violence (which also sparked rebellions in Black urban communities across the country in the 1960s) have been joined by a much more diverse population. So, I see the arc as much longer than a decade, and these issues of representation and social justice are ones that have been embodied in my own work for over four decades. As I told a young Black photographer recently, each generation gets to inherit the struggle and find their own terms of engagement. It’s been good to see Aperture take on the role of an inheritor of that struggle as well. I hope, as it continues forward, that Aperture does not retreat. We all have a role to play in being active and engaged citizens in our respective fields.

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Boot: I feel there has been a distinct arc to our work over this period, and I like the way our arc spawned subsidiary arcs too! The way that the “Vision & Justice” issue led to a thread of projects about race, gender, sexuality, and the idea of beauty: from the magazine’s “Elements of Style” issue (Fall 2017), to the book and exhibition Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (2019) and the book and exhibition The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (2019). All these projects are in conversation with each other.

Meanwhile, I would say Aperture editors are very aware of our past, our institutional history, and the endeavors of those who built it—aware of the points when we have had a positive impact on the story of photography, often when we were boldest in presenting photographers who act as cultural agents of change. And aware, too, of what we didn’t do that we should have.

Given the depths of your engagement with photography over several decades, what have you made of Aperture over the years before 2010? There are many wonderful photographers around, whose story about Aperture is knocking at our door and not being let in; I hope that isn’t yours.

Bey: I’ve been making photographs seriously since the mid-1970s, and started going to galleries to look at work almost from the outset. So it didn’t take too long for Aperture to come on my radar, since I certainly knew and admired the work of Paul Strand, and knew the work of Minor White, and also had something of a front-row seat to the A. D. Coleman vs. Minor White contretemps from regularly reading the Village Voice—which, for anyone interested in progressive politics, along with art and culture, was mandatory weekly reading. And certainly by that time, I had a more passing knowledge of Beaumont Newhall, another Aperture founder, through his History of Photography (1949).

So when Aperture opened in the townhouse on East 23rd Street in 1985, a visit seemed in order, now that they were not just a publication and an organization, but had a publicly accessible space. Visiting that space in 1984 felt very much like my early visits to Marlborough Gallery in the mid-1970s, like I was crossing a social and cultural divide. I was acutely aware that I never saw another Black person in the gallery space while I was there. As it was, it almost felt like entering someone’s home, since one had to be buzzed in and then proceed up the stately, narrow staircase to the second-floor gallery. After those initial visits, I started attending openings, again always feeling that I had momentarily crossed over into another world, but focusing my attention on the photographs, which is what I had come to see. And at the openings, I usually saw only one other Black person, and it was the same one each time, someone whom I eventually came to know and am still friends with. But back then, we would catch sight of each other at those openings with the same mixed feelings of mild discomfort and feigned nonchalance. And yet, our interest in photography kept us coming back.

Boot: What other institutions or spaces were important to you at the time?

Bey: It was pretty clear that the communities that I had become very much a part of—the Studio Museum in Harlem (where I had my first solo museum exhibition in 1979), the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Just Above Midtown, and the Cinque Gallery, to name a few—did not intersect or overlap at all with the community that frequented Aperture. Those African American centered institutions formed a network of support that sustained artists of color in New York at all levels, from the emerging to the established, at a time when they were shut out of the mainstream. The Studio Museum, in particular, was the center of my community, the place where we all found each other. But I was determined that that milieu was not going to be the extent of my engagement with photography. And so, in spite of hardly ever seeing anyone that looked like me in that space, I continued to frequent Aperture.

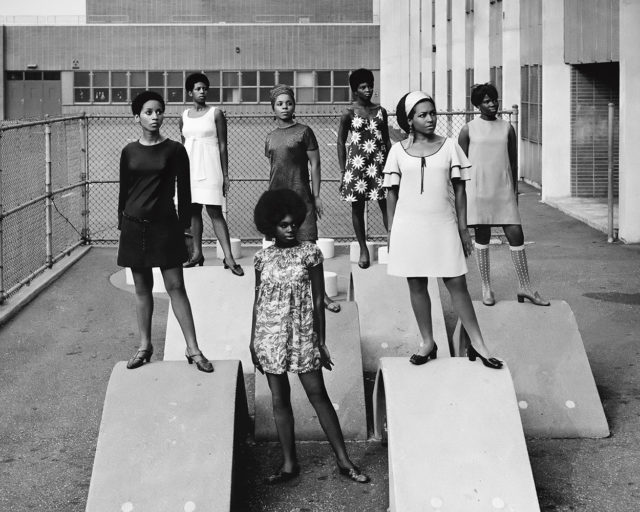

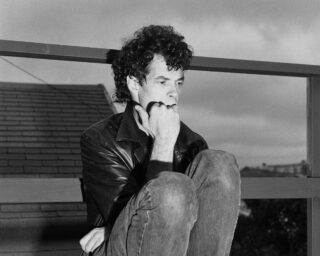

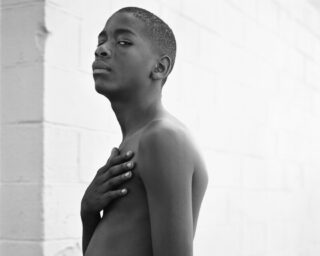

All photographs by Dawoud Bey © the artist

Boot: How did you finally connect with Aperture?

Bey: I was surprised, one day, to get an email from one of the editorial staff at Aperture saying that someone (a mutual friend, whom I knew from the Studio Museum in Harlem’s administration) had told them they should take a look at my work. The email went on to ask, “What kind of work do you do, landscapes?” I was, to put it mildly, bemused, since my entire thirty-year output at that point had been spent making work that was almost entirely portrait-based, and I’d had a number of both mainstream museum and gallery exhibitions. But I set a date for a meeting to show them the project I was in the midst of, Class Pictures (2002–6), which they were immediately interested in and committed to publishing at that first meeting. Class Pictures was then published some two years later, after I spent an additional year making the work.

So no, I wasn’t turned away, nor had I been knocking on Aperture’s door. But it was certainly an auspicious beginning. What I hadn’t given much thought to, before other Black photographer colleagues pointed it out to me, including those who were “not let in when they knocked at the door,” was that with the 2007 publication of my book Class Pictures, I became only the second Black photographer to have a book published by Aperture. The publication of the “Vision & Justice” issue of the magazine, and the subsequent publication of books by LaToya Ruby Frazier, Kwame Brathwaite, Deana Lawson, and now Ming Smith (along with the publication of The New Black Vanguard), was a moment for me when, finally, those two communities that I’ve long navigated between found some significant common ground. It’s a breakthrough moment for Aperture—a little late in the day, for sure, but hopefully, the organization will continue to move forcefully forward in reflecting the true diversity of the field in a way that its history has not always reflected. It’s not only good cultural citizenship; it’s good business, too, as the runaway success of “Vision & Justice” made clear.

Dawoud Bey: An American Project is on view at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, through March 14, 2021. The exhibition opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, on April 17.