How Not to Design a Photobook

Spread from Martin Parr, Hong Kong Parr (GOST, 2014). Courtesy Stuart Smith

After studying design and photography at the School of Documentary Photography at Newport (now part of the University of Wales), Stuart Smith worked as a designer for the Architectural Association School of Architecture and Phaidon Press. He later established his independent bookmaking practice in 1994. Smith has worked on over forty books with Aperture’s Executive Director, Chris Boot, at Phaidon, Chris Boot Ltd., and, now, at Aperture. In advance of Smith’s first workshop for Aperture, September 17–18, Boot talked with the designer about “how not to design a photobook.”

Spread from Larry Towell, The World From My Front Porch (Chris Boot, 2008). Courtesy Stuart Smith

Chris Boot: You’ve been editing and designing photobooks for almost thirty years. I’m guessing you’ve designed hundreds of books by now. Which books that you’ve designed are you most proud of, and why?

Stuart Smith: I think I have done around one thousand books, more or less, and in the last fifteen years mostly photography.

The books that give me the most satisfaction are the ones where they feel more like a collaboration, and where I have been instrumental in editing and steering the book, in terms of the sequence, the picture edit, the overall size and feel of the book, and the reproduction and quality of the printed images. This is where the magic and unexpected things happen.

I am not very interested in designing a book if the photographer only wants me to be a digital monkey. If I have nothing to bring to the plate then I don’t need to be involved.

With most books my team and I work on, we’re very involved in the creative thinking about what the book is. These are the books I have the greatest fondness for, for example Martin Parr’s Hong Kong Parr, Mark Power’s The Sound of Two Songs, Larry Towell’s The World from My front Porch, Hiroji Kubota’s Hiroji Kubota Photographer, James Nachtwey’s Inferno, and Eve Arnold’s All About Eve.

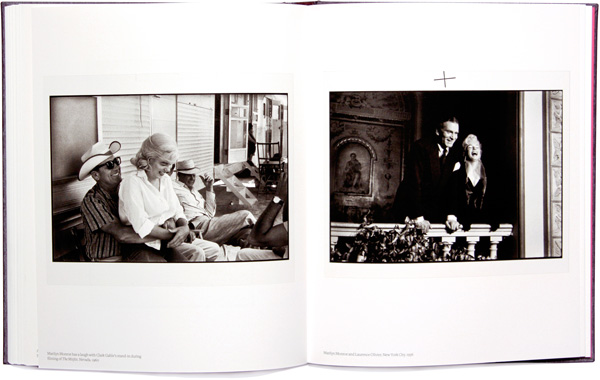

Spread from Eve Arnold: All About Eve (TeNeues, 2012). Courtesy Stuart Smith

Boot: Your workshop is titled “How NOT to Design a Photobook.” What is it that photographers often get wrong?

Smith: Because photographers are visual, they usually assume two things: that they can design and that they can edit. But they benefit by letting someone else in. It doesn’t matter how well-known a photographer is, the fact is all photographers need a good editor, someone who they can trust checking or proposing picture and sequence decisions. It’s probably the most important part of putting a book together. Often the photographer is too close to the work, or to certain images, and they have a tendency to want to use more images, when they should let some of them go. The reverse can also be true. A photographer can become fixed on particular pictures. I usually want to see a wider edit than the photographer initially has in mind, and quite often between ten and twenty percent of the final picture selection will come in from this broader selection. This doesn’t seem like much, but it can make the difference between the mediocre and the sublime.

I’ve assembled all my experiences of putting books together to present as a workshop, and, of course, it’s a kind of joke to talk about how not to do a book. The do’s as well as the don’ts are all in there. I hope I can help guide people towards the best book they’re capable of making.

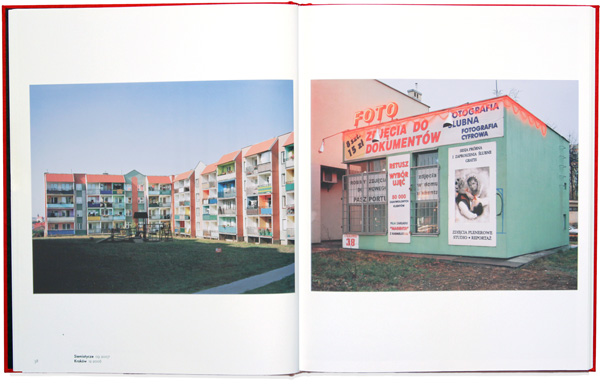

Spread from The Sound of Two Songs: Poland 2004–2009 (Photoworks, 2010). Courtesy Stuart Smith

Boot: Sometimes you work as designer of some books when someone else is working as the editor. But you also work on many books as both editor and designer. Do the roles of editor and designer naturally belong together? Is your design better if you are also the editor?

Smith: If I design and edit the book, then much of the work is in the edit. By the time we get to the design, we have established an understanding of the work, and what type of book it is going to be, as well as what the range of pictures are that it will include. It is more likely to be nuanced, and have subtlety, compared to if I am given someone else’s selection of pictures. Also, how a book works, its pace and flow, will depend on pairings and I usually need options to make the book work.

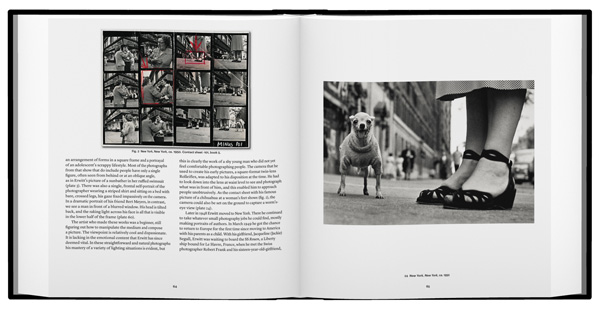

Elliott Erwitt, Home Around the World (Aperture, 2016). Courtesy Aperture

Boot: The book you’ve most recently designed for Aperture and the Harry Ransom Center is Elliott Erwitt: Home Around the World. Is this about the tenth book you’ve done with Erwitt, even though only the first with us? What’s the secret to being adopted by a major photographer in this way?

Smith: I think it’s the fifteenth. The secret, as with most photographers, who are a skittish bunch, is to be there to catch them. If you are able to do that then you are going to have a great relationship; they trust you. And then they show you pictures that they may not want others to see. All that applies to my work with Elliott. Also I have to get on with the photographer to do good work. And we have to have fun too!

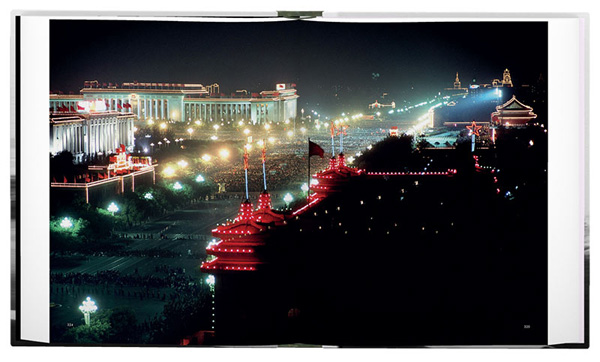

Spread from Hiroji Kubota Photographer (Aperture, 2015). Courtesy Aperture

Boot: Is there one recommendation you can offer a photographer reading this who won’t be able to attend the workshop that they should consider when preparing themselves for the making of a photobook?

Smith: Do a tight edit but then also show a broader B edit. Unless you’re highly proficient as a designer, don’t try to do the graphic design on the book yourself. Don’t print your book via print-on-demand—this is only good for showing your grandmas 85th birthday party pictures, not for showcasing the beauty of your photographs.

Aperture will host a two-day workshop with Stuart Smith on September 17 and 18, 2016. Intended for photographers who are prepared to transition their images into book form, the workshop will focus on editing, sequencing, and pairing photographs, as well as how to design a successful and thoroughly considered photobook. Registration ends September 7. For more information about Smith’s workshop and other upcoming workshops at Aperture, please visit aperture.org/workshops-classes or contact education@aperture.org.