No Country for Young Men

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran’s image abroad has been defined by its politics. In this newsroom universe, Iranian women have been front and center in the frame, the Western gaze seeking their exotic attire and problems. Iranian men, on the other hand, have been strangely absent from this picture, unless they are bearded politicians or directors of art-house movies. Young Iranian men, in particular—perennially present in their own cities in the countless murals of fallen heroes of the Iran-Iraq War—became invisible to the world, their issues lost in the daily economic and political maelstrom of the country.

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

Abbas Kowsari, one of Iran’s prominent photojournalists, noticed the lack of representation of men in images about Iran while working as an assistant to the late Sadegh Tirafkan, who addressed issues of masculinity in his internationally celebrated art photography. “Maybe it was because of the wars that Western powers were starting in the region,” Kowsari says, referring to the consecutive wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. “There was more interest in women’s issues and women photographers taking photographs of women.”

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

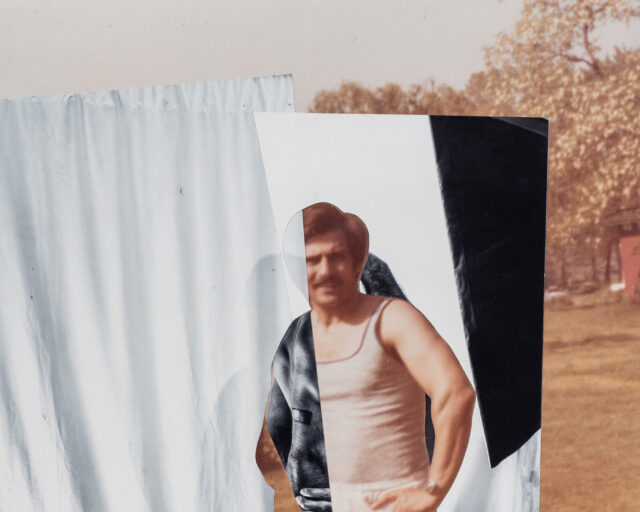

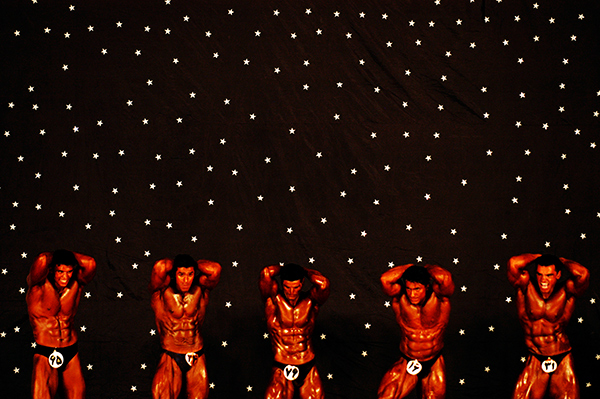

In 2006, Kowsari began to focus on Iranian men in a series of photo-essays titled Masculinity. These images feature bodybuilders preparing for the stage (from oiling up to parading their pumped-up muscles) and wrestlers (who enjoy hero status in Iran because of the regular medals they bring home) captured in the moments before and after competition. “I really wanted to show that men can also feel fatigued or defeated,” Kowsari says. His photography addresses both the vanity and the vulnerability of men. His latest project, begun in 2015 and ongoing, documents male public bathhouses that operate in the poorer parts of Tehran.

Courtesy the artist

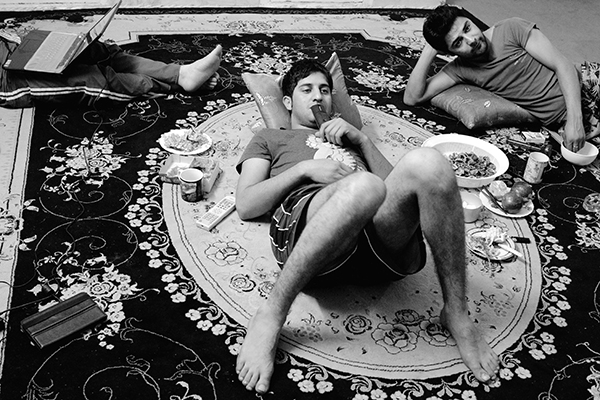

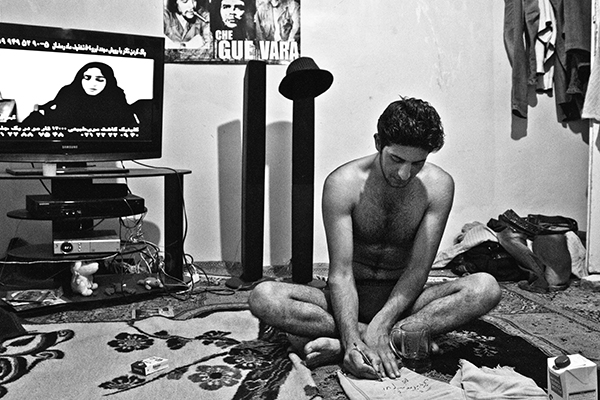

While Kowsari’s work records men in public spaces, Najaf Shokri’s series Bachelors (2009) looks at the private spaces of a group of friends in the town of Karaj, some forty kilometers from the capital. Young men are seen whiling away their time at home, uninhibited and often half naked. Out of work and in retreat from the policed streets after the 2009 postelection turbulence in Iran, they depict a generation’s lassitude. It is surprising how relaxed and open these men are in front of the camera. “They were happy that I was photographing them,” Shokri says, “as if their lives became more meaningful by being photographed.”

Courtesy the artist

Although Shokri’s photo-essay has been picked up for group exhibitions in the United States and Canada, he cannot show these photographs in Iran, as they reveal too much skin. Despite the fact that his series is reminiscent of the work of Larry Clark, in the intimate portrait it provides of friends, Bachelors is being both subjected to censorship inside the country and largely dismissed by the outside world, due to a tendency to favor stories from Iran that are told through images of its women.

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

In another cloistered environment, Behzad Jaez has recorded the lives of young men usually hidden from view: seminarians in religious schools across the country, whom he began photographing fifteen years ago. These are the aspiring ayatollahs of the future—potentially the elite clerics who will lead the country’s politics through religion. Jaez’s series Turbanites (2014) was exhibited in Tehran last fall and published as a book by Nazar Art Publications in 2017. But this glimpse into the austere lives of these religious students has aroused the ire of his secular friends, condemning his choice to photograph the young clergy, who they feel should not be valorized. Jaez notes, however, that this community is not as monolithic as it may seem: “Ironically, not all of these guys decide to take the robe when they finish their studies,” he explains.

Courtesy the artist and Ag Galerie, Tehran

Aspects of Iranian men’s lives provide a wide scope for social documentary work about Iran as a whole. Men, especially the young, face overwhelming demands in a traditional society that defines manhood as a role of protecting and providing. In a country where the government is failing to create enough jobs, reduce rampant economic corruption, or prevent the current frightening increase in drug use, these men face challenges that are as complex as the issues that afflict the women and ultimately affect the whole population, regardless of gender. Photographers who choose to focus on the country’s men accept that their images may not find a regular spot in international exhibitions on Iranian photography as easily as works by photographers who zoom in on Iran’s women. And they know that these images of Iran’s masculine population almost never make it to the front pages of major publications in the West. In the gaze of foreigners and Iranians themselves, Iran is no country for young men.

To continue reading, buy Aperture, Issue 230 “Prison Nation,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.