Doug DuBois on Chris Killip In Flagrante Two

My first encounter with In Flagrante (1988) was in San Francisco, where the year it was released I made regular visits to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights bookstore, and to the used bookstores sandwiched between the strip clubs on Broadway. It worked like this: I would go to City Lights to touch and ogle the unaffordable photobooks, read a few pages of an ever-growing list of post-structuralist or feminist literary theory and postmodern art criticism, then head over to Broadway to scour the bins in hopes of finding something more affordable (one such find was a $14.95 copy of Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s Evidence, from the True Crime section of Columbus Books).

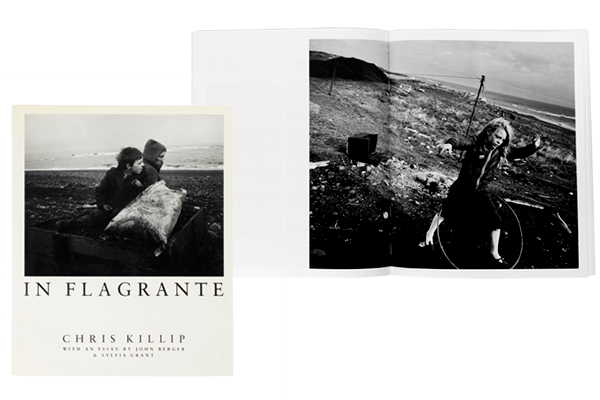

In Flagrante, released by the progressive British imprint Secker & Warburg, known for publishing first editions of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Simone de Beauvoir, J. M. Coetzee, etc., found its way into the photography section at City Lights. I remember thinking, I should buy this, but I didn’t. So, like many people, I came to study the book in earnest through the Errata Editions facsimile from 2008. Here’s what I Iearned:

1. You can shift an image wherever you need—left, right, or off-center—so that the gutter bisects the photograph precisely where you want it, not simply where it lands relative to the page border. (While hardly an innovation unique to Killip or this book, this was a revelation for me.)

2. Photographs of children can be more than ciphers for innocence and suffering.

3. Anger, attenuated by art, holds fast.

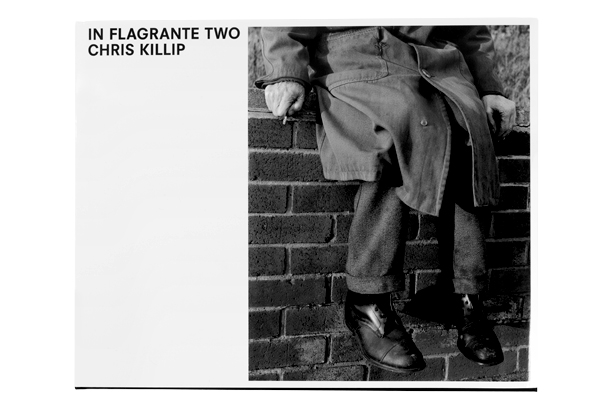

Chris Killip, In Flagrante Two • Steidl • Göttingen, Germany, 2015 • Designed by Chris Killip and Victor Balko • 14 1/4 x 11 1/4 in. (36.1 x 28.6 cm) • 110 pages • 50 tritone images • Hardcover with jacket • steidl.de

In a recent interview with Martin Parr, Chris Killip shared a memorable (and snarky) comment from photographer Brian Griffin about the layout of In Flagrante: “I always knew that you were very fond of the gutter but I had no idea that you’d end up in it.” In this year’s newly designed, discreetly re-edited edition, In Flagrante Two, Killip reorients the book from portrait to landscape format, placing all the photographs on the right-hand page. The vertical images are sidewise to maintain their scale. I have to admit that I miss the choreography of the first edition; the engagement of the photographs with the gutter contributed to a restless dynamic that carried through the sequence of images. With its vastly improved reproductions and unencumbered views, however, In Flagrante Two invokes the statelier rhythm of a print portfolio.

Over the years, much has been made of Killip’s terse introduction to the original In Flagrante, especially its final sentence: “This book is a fiction about a metaphor.” That introduction, as well the other texts (by W. B. Yeats, John Berger, and Sylvia Grant), are absent from this new edition. The Scottish poet Don Paterson, writing for the Financial Times, celebrated this paring away with a parenthetical aside reserved for Killip’s best-known line: “I have still no idea what he means. The work is not a fiction, nor is it concerned with metaphor, if either of these words are to be conventionally defined.” However, in the first edition, Grant and Berger had argued together: “Fiction, I think, because it is a story, not just information. About a human tragedy not an accident. Metaphor because it is through metaphor that, at first and last, we seek for meaning.”

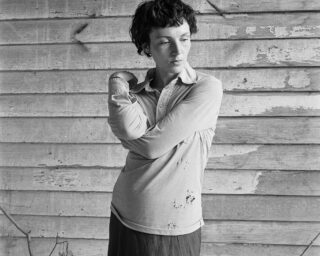

The photograph May 5th 1981, North Shields, Tyneside, is one of the three images newly added to In Flagrante Two. The date commemorates both the day the photograph was made and the death by hunger strike of IRA leader Bobby Sands, in HM Prison Maze. The image is placed within a sequence of photographs depicting food (grown, harvested, canned, and eaten), families at rest, dogs, children, and young adults at play. In the photograph May 5th, there are five children, two standing on a wall posing for the camera, the other three in various stages of either climbing up to pose, or clambering down to leave. Killip is at a distance and well above the children, so the background opens up behind them to reveal a housing estate with burned-out flats and the graffitied slogans “Bobby Sands Greedy Irish Pig” and “Smash the IRA.”

In 2012, the filmmaker Michael Almereyda interviewed Killip on the occasion of his retrospective exhibition Arbeit/Work at the Museum Folkwang in Germany, in which many photographs, including May 5th, were being shown for the first time:

Killip: I . . . went to the only place I knew that Bobby Sands was memorialized in any way. It was in a public housing project in North Shields, which is fiercely Protestant, and I photographed the graffiti in its context. Kids came up and asked could they be in the picture, and I said sure. For me, it was a very sad picture. . . . it’s about how history is lived by working-class people, and how bigotry is passed down, restraining and constraining lives.

Almereyda: The children seem kind of innocent of it.

Killip: They could be innocent of it, but they’re not unaffected by it. Your innocence can’t last. Bigotry is powerful.

Killip goes out to photograph graffiti in reaction to the death of Bobby Sands. He allows a group of children to enter the frame and pose for him. Undoubtedly oblivious to the graffiti behind them, the children think the photograph is of, if not for, them. Killip, however, is quite aware that the children’s presence enlarges the meaning of the image from an angry, ironic commemoration to a more conflicted image about the etiology of bigotry, nationalism, and the conflict in Northern Ireland. The belated inclusion of this photograph within the new sequence shifts meaning in the book, just as a novelist might by adding or excising a paragraph, a poet by removing a stanza, or the painter in Len Tabner painting, Skinningrove, N Yorkshire, who busily paints a roiling storm in front of an overcast seascape. All are fictions and metaphors at work and play.

Chris Killip, In Flagrante • Secker & Warburg • London, 1988 • Designed by Peter Dyer • 9 5/8 x 11 7/8 in. (24.6 x 30.2 cm) • 96 pages • 50 black-and-white images • Softcover

Perhaps the central motivation and best measure of Killip’s photographs are their distillation of inchoate feelings—anger, righteousness, respect—into a carefully considered argument and concise form. In 1989, poet and critic Daniel Wolff concluded his review of In Flagrante with the question: “What can we do to respond to the kind of public neglect documented in Chris Killip’s book?” In February of this year, poet and critic John Yau titled his review of In Flagrante Two “What Will You Do About Chris Killip’s Challenge?” Dana Lixenberg, Khalik Allah, Zoe Strauss, Dave Jordano, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Stephen Gill are just a few of the artists answering this challenge, and presenting their own. But whether or not we do anything in response to Killip’s photographs is hardly a measure of their worth, nor is the negligible change in conditions that gave rise to their making a cause for indifference. The project of art is long, and my answer to Yau’s question is simple: keep working.

DOUG DUBOIS has received fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, MacDowell Colony, and National Endowment for the Arts. DuBois teaches in the College of Visual and Performing Arts at Syracuse University, and his most recent book is My Last Day At Seventeen (Aperture, 2015). A survey of his work, In Good Time, opened at Aperture Gallery in March 2016.