Unpacking Ed Ruscha

Ed Ruscha, Pool #7, from the portfolio Pools, 1968

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Ed Ruscha’s artist books confounded archivists and artists alike when they were first published. In 1963, the Library of Congress mailed back the copy of Twentysix Gasoline Stations he’d submitted (a rejection the twenty-six-year-old artist memorialized in a cheeky Artforum advertisement). That same year, Artforum’s editor Philip Leider pointed out that the book—cheaply printed and composed of twenty-six black-and-white photographs of gas stations along Route 66—was “so curious, and so doomed to oblivion, that there is an obligation, of sorts, to document its existence.” Of course, that confusion was the intended effect. “People would look at it and say, ‘Are you kidding or what? Why are you doing this?’” Ruscha told the New Yorker in 2013. “That’s what I was after—the head-scratching.”

Ed Ruscha, Conoco, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1962, from the book Twentysix Gasoline Stations

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

A new exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center, part of the University of Texas at Austin, doesn’t lessen Ruscha’s artistic ambiguity, but it does pull back the curtain on his process. Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance marks the first showing of the Ransom’s Ruscha collection, acquired in 2013. (The Los Angeles artist has divvied up his papers between a number of institutions, including the de Young Museum and the Getty Research Institute.) Although Ruscha’s oeuvre is broad—encompassing painting, printmaking, photography, even video—the Texas archive contains materials tied specifically to his pioneering artist books and two public library commissions, a panoramic landscape for Denver Public Library and a series of site-specific word paintings for the Miami-Dade Public Library.

Archaeology and Romance narrows its focus to the sixteen artist books Ruscha made between 1963 and 1978. More than one hundred and fifty objects are displayed across the Ransom Center’s first floor, including rare copies of publications such as Business Cards (1968) and Babycakes with Weights (1970) and a case, over twenty feet long, that allows the accordion-folded Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) to stretch out to its full length. But it’s the preparatory materials accompanying these publications—studio notebooks, paste-ups, even invoices for printing and binding—that offer the most intriguing glimpse into the artist’s mind.

Ed Ruscha, Preliminary notes, Some Los Angeles Apartments, 1965

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Jessica S. McDonald, photography curator at the Ransom Center, was among the first to comb through the archive. Ruscha, she discovered, was a consummate multitasker. “Something I found surprising was just how much he was working on at any one time,” McDonald told me recently. A page of notes relating to his 1965 book Some Los Angeles Apartments also sports a few lines at the bottom, reading “Fourteen Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass.” That offhand note went on to become, three years later, a book titled Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass. (There are also some other delightful, apparently discarded, book ideas, including Several Ash Trays, a Speedometer, & a Fish.) “Finding those traces all through the works,” McDonald explained, shows that Ruscha’s process “was more of a web than any kind of linear progression.”

Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass was the first of the artist’s books to include color photography. Sorting through the materials related to the project, McDonald came across Ruscha’s handwritten specifications for the book. In underlined block letters, he had written “THREE COLOR NO BLACK.” Color photographs are typically produced using four layers of ink—cyan, magenta, yellow, and black—but in this case, he eschewed the final, black layer. It was an unorthodox printing choice that could, perhaps, have been a money-saving measure—except that Ruscha also added fifty-two blank pages to the book, indicating he wasn’t particularly worried about the expense. “If that decision is what I think it is, that’s a really kind of brilliant experiment,” McDonald said. “It’s a way to get the pictures to look really bright and a little bit unsettling, in that you can’t quite ground them in the shadows. I just didn’t expect to see that, because his photos are usually so straightforward.”

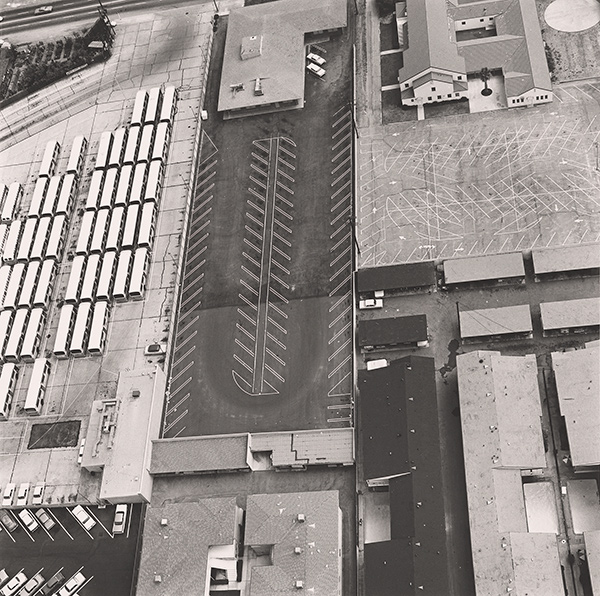

Ed Ruscha, State Board of Equalization, 14601 Sherman Way, Van Nuys, 1967, from the book Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

This lack of artistry is one of the hallmarks of Ruscha’s artist books. “The photographs of gas stations are bad photographs on purpose,” McDonald noted. “He’s trying to do the opposite of what a photographer trying to make an artistic photograph would be doing.” In a 1965 Artforum interview concerning his second book, Various Small Fires and Milk (1964), Ruscha explained that it didn’t even matter to him who took the photographs. “In fact, one of them was taken by someone else,” he said. “I went to a stock photograph place and looked for pictures of fires, there were none.” For his 1967 book Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles, Ruscha went so far as to hire a commercial photographer to capture the aerial shots.

Compared to his paintings, Ruscha has said that the books were “easy.” “I didn’t have to struggle, and I felt like I was operating on blind faith more than on any kind of decisions. It was as though somebody else was designing them.” That self-assurance is also visible throughout the archive. McDonald came across a sheet of paper, labeled “ROUGH” in orange crayon, outlining the order of Some Los Angeles Apartments. Despite the label, “it’s not rough at all. It’s precisely how the book is,” McDonald said. “So if he’s somebody whose rough draft is essentially pretty darn close to the final draft, then that shows a certain level of confidence.”

Ed Ruscha, “Rough” layout sequence, Some Los Angeles Apartments, 1965

© the artist and courtesy Harry Ransom Center

Archaeology and Romance chronicles an artist becoming increasingly sure of his vision. For Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Ruscha took far more than twenty-six photos, narrowing his selection to images he felt were devoid of feeling; for Real Estate Opportunities, published in May 1970, he took just four rolls of film in total. “A lot of people who would intentionally call themselves a photographer, somebody trying to make ‘good photographs,’ might get one good picture in forty-eight,” McDonald said. “He just needs to get the information. He’s not trying to make a great picture. By 1970, he already knows what he needs—he just goes out and gets it.”

Ed Ruscha: Archaeology and Romance is on view at the Harry Ransom Center, Austin, Texas, through January 6, 2019.