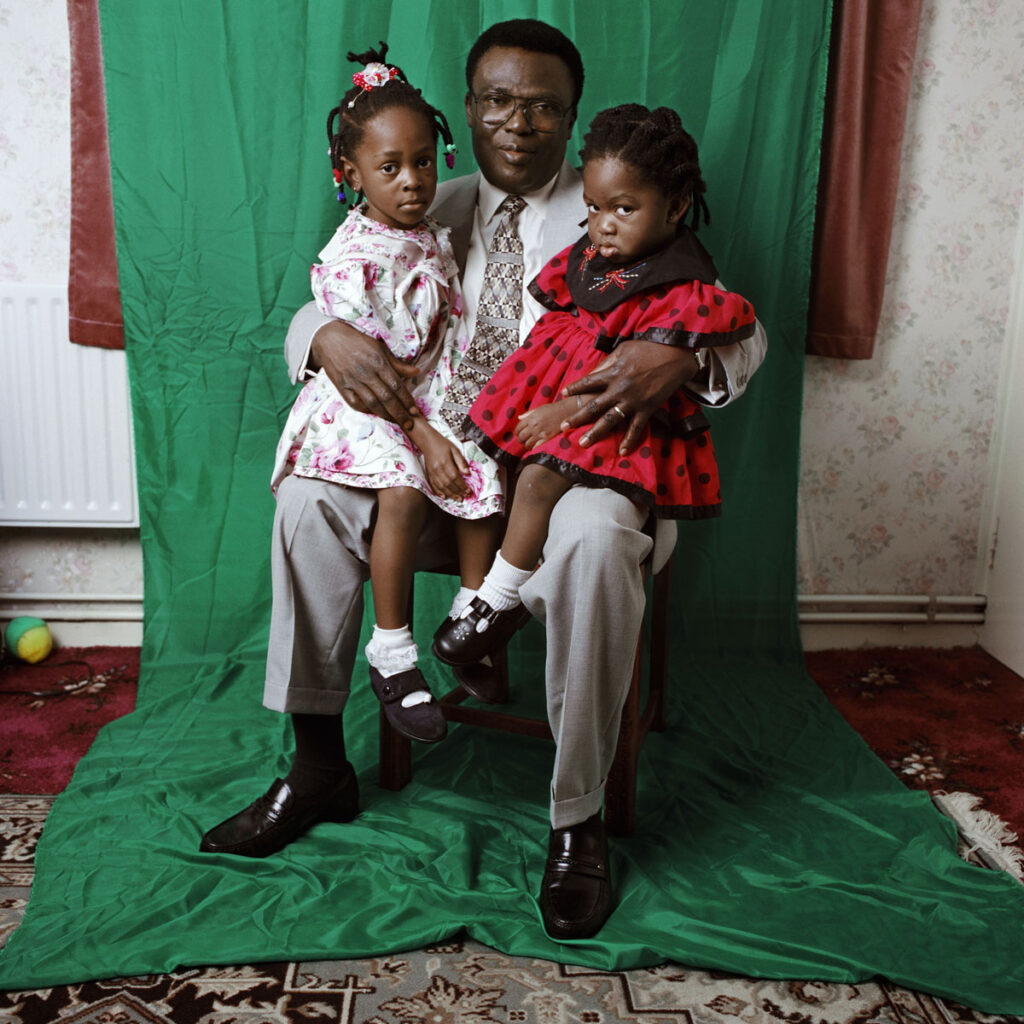

Eileen Perrier, from the series Afro Hair and Beauty Show, 1998–2003

Like many photographers, Eileen Perrier was given a camera as a child, and that’s where her story began. While studying for her university entrance exams, she took an introductory course in photography, and another in dressmaking, and found she loved photography. She studied at the Royal College of Art in London. Her initial images were of people she encountered in Ladbroke Grove and other parts of the city. Soon she met the photographer Armet Francis, one of her heroes, who became a mentor, showing her how to handle her prints and encouraging her to put work forward for publication.

‘‘I just got the bug, you know, that thing where everyone says the magic of being in a dark room and then you see an image appearing in there,” Perrier said recently. Her work is now the subject of a solo exhibition, A Thousand Small Stories, at Autograph, in London’s East End. As the curator Bindi Vora explained, the title illustrates how each individual experience, no matter how minor it may appear, contributes to a bigger, shared narrative. This concept aligns closely with the sociologist Stuart Hall’s insight that images can express meanings that reach far beyond their immediate surroundings, enabling us to envision and comprehend more than just what is presented in the frame.

The exhibition opens with When am I gonna stop being wise beyond my years?, a series from 2024 that delves into the challenges teenage girls encounter as they navigate social media, body image, and misogyny. Perrier’s fascination with the complex politics surrounding beauty is further evident in her renowned portraits from the late 1990s and early 2000s, particularly in Afro Hair and Beauty Show (1998–2003), which emphasize the important role of hair and hairstyles as markers of cultural pride and resilience. The young participants sit there, oozing self-confidence.

What makes this section special is an installation created with replicas of Black haircare products from the ’90s, on plinths. Perrier has collected these products over the years, and Vora noticed, in her research, that their packaging has often stayed consistent. Vora felt that displaying them would demonstrate “in a very tangible way, the aspirational branding still in use today.”

In 1995, Perrier made a pivotal trip to Ghana. Until then, most of her images were made in black and white. In Ghana, she gained confidence in using colour. “All the images I was seeing at that time were black and white,” she said, mentioning the kind of photography commissioned for foreign charities. “And I just didn’t want to emulate or recreate the images they were portraying.” In one close-up of a bottle of Cussons baby powder, the pale blue wall in the background complements a white bottle with a picture of a blonde baby and the name of the product in baby blue. Perrier, who regularly used Cussons as a child, sees it as an emblem of neocolonial economics: at the time, the company did not bother to differentiate the packaging for an African market.

Perrier frequently immerses herself in communities, a spirit of collaboration that resonates in her series Red Gold and Green (1996–97), which was commissioned by Autograph. Here, she joined forces with first-, second-, and third-generation British Ghanaians, friends of her mother’s and extended family, to craft intimate portraits within the comfort of her subjects’ London homes. Perrier’s temporary home studios beautifully reflect the complex blending of modern migrant identities. Symbols from various homelands subtly appear in the background, and vibrant textiles recall longstanding traditions of African studio portraiture. In the exhibition, a vitrine displays ephemera connected to the series, showing, as Vora notes, how Perrier’s “three decades of working as an artist come together beyond just the final images.”

All photographs courtesy the artist and Autograph, London

Another celebrated series considers a painful memory. As a child, Perrier faced teasing for the gap in her teeth, a feature she rarely saw in others around her. Aware that it is seen as a sign of beauty in various cultures, she made the series Grace (2000), which comprises images of people with their faces angled towards the camera, facing right and smiling so their teeth are on display. Perrier herself features in a self-portrait along with a portrait of her mother. The personal connection Perrier builds with her subjects goes beyond simply taking their photographs. Instead, a sense of social engagement permeates her work—an alluring reminder that our experiences of love and fear are intertwined, allowing us to perceive them through one another’s perspectives.

Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories is on view at Autograph, London, through September 13, 2025.