In a World of Loneliness, One Photographer's Search for Community

Eli Durst, Gwen in Circle, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Eli Durst’s first monograph, The Community, an examination of “the fundamental search for community in America,” arrives this spring in a moment of unprecedented isolation and alienation. The COVID-19 pandemic has rendered the act of gathering—a behavior coded into our very DNA—unsafe and, in most of the country, illegal. But even before the lockdown, sociological studies have long shown that in-person community is on the decline, and that the practice of building intimacy and identity in a group is migrating, like seemingly everything else, into the digital sphere. I wanted to discuss this—the uncanny relationship between the book and the state of the world it’s entering—but also get a better general understanding of Durst’s photographic approach as he takes on more editorial assignments. We spoke in late April, mediated by our screens, of course, a mode of conversation that felt appropriate for reasons beyond public health mandates.

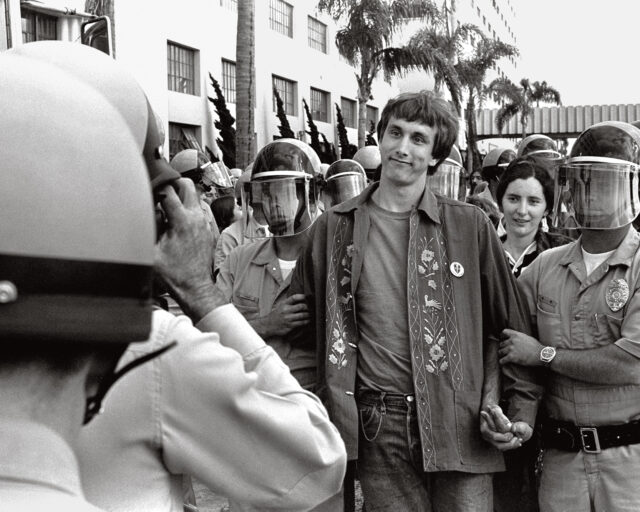

Eli Durst, Adam, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Gideon Jacobs: To begin, I wanted to ask you about the end of your book, the very direct statement of intent on the final page: “Put simply, these photographs are about the search for purpose and meaning in a world that both demands and resists interpretation.” I was kind of surprised to see you explain what the work is about in such a straightforward way. What made you want to articulate that?

Eli Durst: Well, I wanted to give some context without having to provide titles or details about each image. I felt like a little bit of explanation would give people some more context to interpret the book. However, I put it in the back of the book for a reason—so the viewer can look at the work first. I kept the explanation brief for this same reason. I want the viewer to interpret the work for themselves, but I don’t want to be intentionally opaque.

Eli Durst, Melting Ice Cream, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: It seems like a tricky balance to strike for all photographers, finding a comfortable zone between giving context, explaining, priming, and letting the work speak for itself. Where do you think you fall on that spectrum? Is it something you think about?

Durst: I generally don’t like over-explanatory text, because I want to figure out the work for myself. But at the same time, I think you need to give the viewer a framework through which to interpret the work. I hope the book remains a mysterious object, even with the text in the back.

Eli Durst, Casa Ritual, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: I think it does! Let’s talk about that framework. What is the link between community—the more overt subject of the book—and our search for purpose and meaning—the more subtle subject?

Durst: The book is about pursuing physical community—something that seems even more important now that we have been deprived of it for public-health reasons. The series is not really meant as a documentary project studying the unique qualities of each group or activity. I’m more interested in the commonalities across all these different pursuits. What is everyone after? Why, in the twenty-first century, congregate at a rec center or church basement? What is at stake? What do people gain from being together in physical space? What do people need from each other, from a community?

Eli Durst, Knot Tying with Dante, 2017

Courtesy the artist

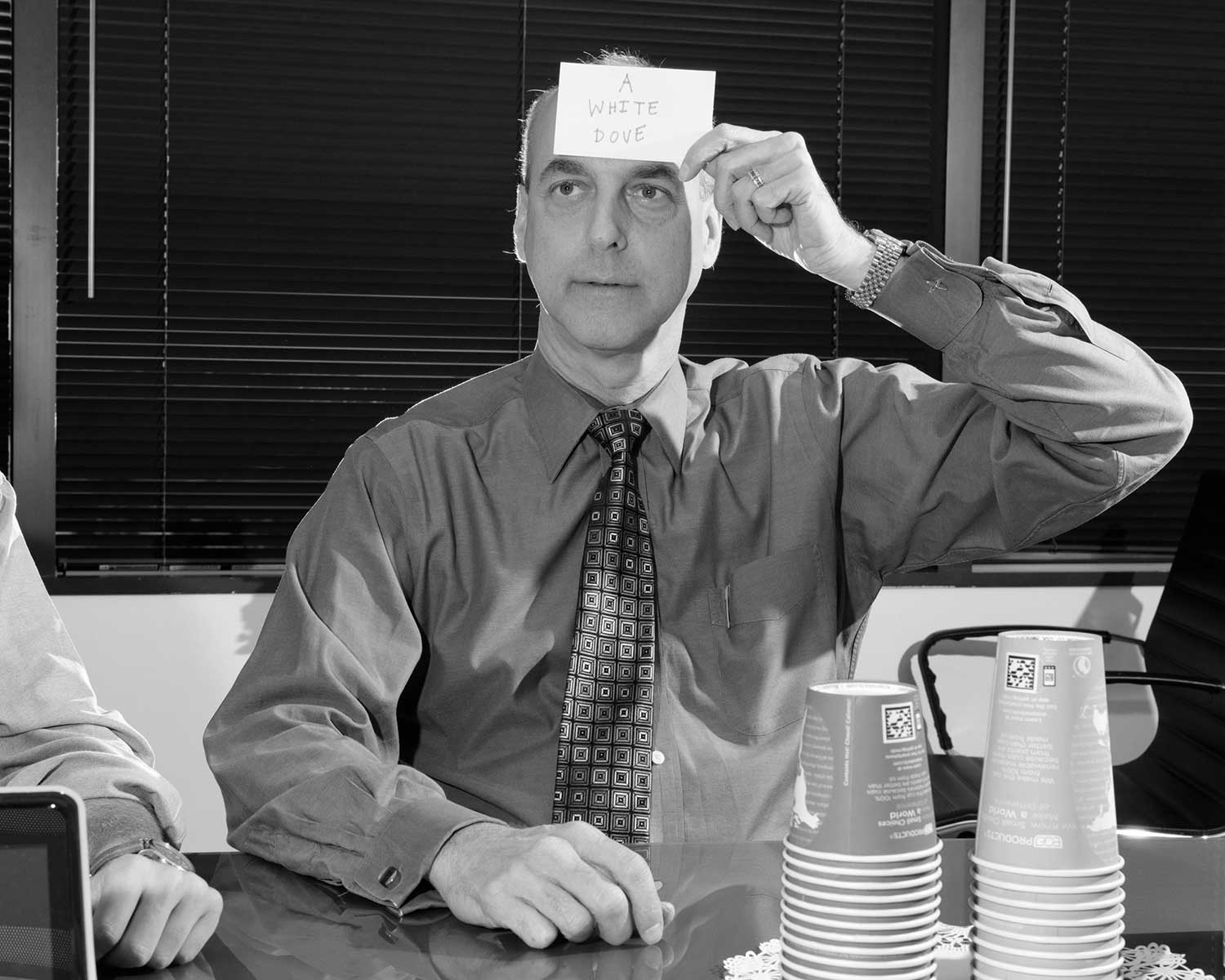

Jacobs: Something I think a lot about when looking at your pictures is that, for community building activities to be effective, you need an earnest buy-in from the whole group. People can’t be too cool for school. Your photographs are often striking to me in the way they capture earnestness, a rare kind of sincere participation. What is it about that quality in a person or a moment that attracts you?

Durst: That’s true. You have to be vulnerable in some way, open yourself up to other people. With the team-building exercises, people think they’re silly or ridiculous, but that’s the entire point, for your boss to do something that they would never normally do, to make yourself look ridiculous, to give up your ego in some small way. It’s not that trust falls give you some business acumen you lacked before. It’s that you bond with someone by acting outside of yourself.

Eli Durst, Lightbulb, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: That vulnerability and ridiculousness can make your pictures kind of funny. Do you ever fear that humor? Do you ever worry that these earnest subjects, when viewed by those outside of the team-building activity—especially when viewed by a critical, cynical photo audience—will be laughed at for the wrong reasons?

Durst: Definitely, and it’s something that I really tried to work against in the edit of the book. I cut out some photos that I thought were successful, because they felt too jokey and undermined the project as a whole. But humor is still a part of the work. The statement at the end of the book about “a world that both demands and resists interpretation” alludes to a certain absurdity in our pursuit of meaning. When I started making these photos in graduate school, I gravitated towards funny Americana-type subjects, like bingo for instance, but I quickly realized that I wasn’t satisfied making ironic photos. I also didn’t want the pictures to become overly sappy. The tone of the project changed a lot as I was making it. I tried to learn from the pictures.

Eli Durst, Sam and Ben, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: What about this body of work feels uniquely American to you? Could this book have been made in another country or culture?

Durst: I don’t think so. The core of my work, regardless of series, has always focused on American identity and suburban iconography. I think the need for a sense of purpose is universal, but the setting in which this pursuit unfolds in The Community is uniquely American. I was an American studies major in undergrad, and I’ve always been drawn to photography for its ability to investigate or think critically about the landscape around me, the landscapes that I feel closest to.

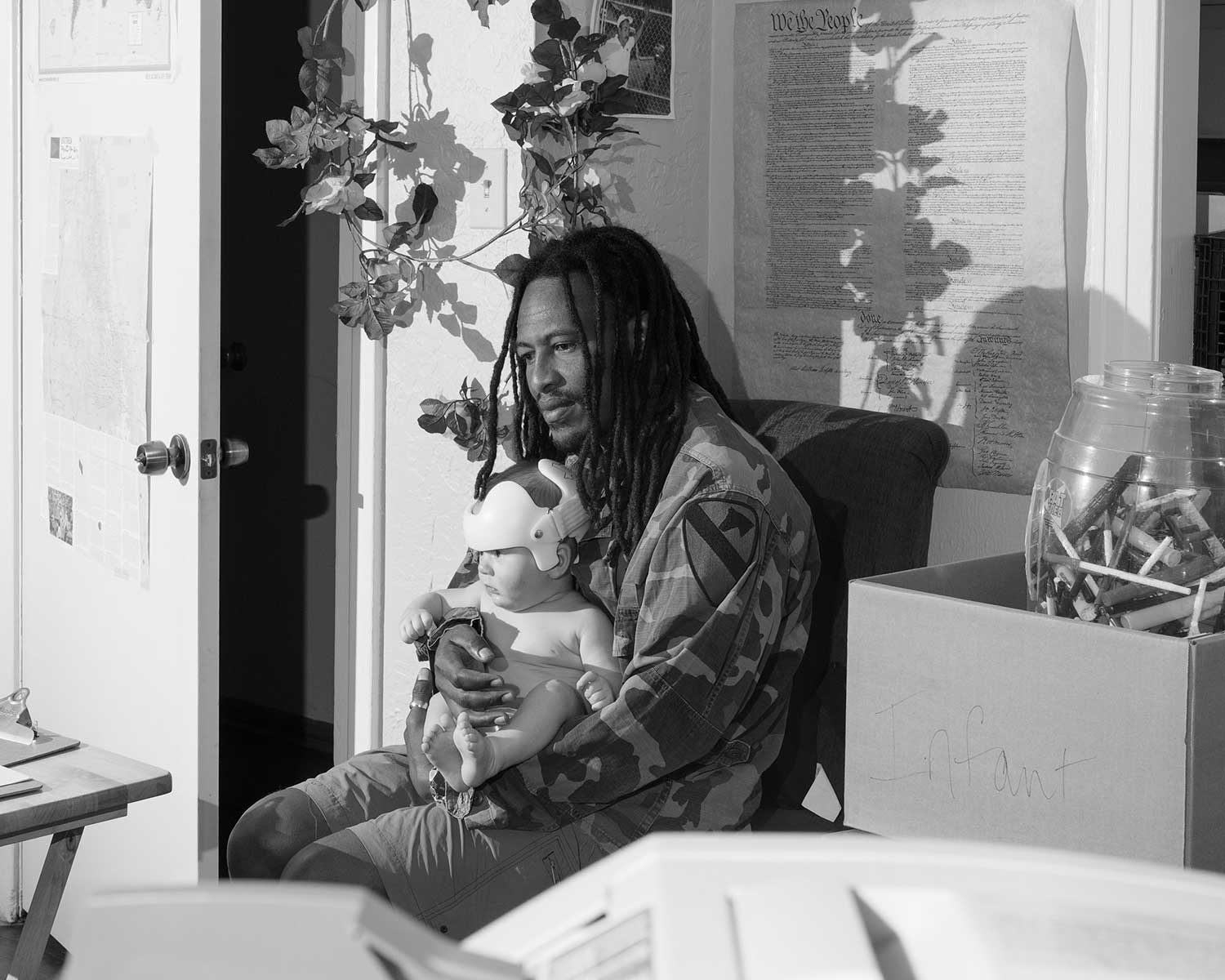

Eli Durst, James with Baby, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: Did this have anything to do with why you called the book The Community instead of simply Community?

Durst: I liked The Community, because it almost made it feel like this was one fictional community center, in which all these events were unfolding simultaneously.

Jacobs: It seems like one of the possible consequences of the pandemic might be that it has sped up the migration of community from the real world to the digital one. Do you see your book as covering the last vestiges of something? Maybe something that won’t really exist for the next generation?

Durst: I was reading the book Bowling Alone (2000) when I started making the work and thinking about the disappearance of certain aspects of American culture. I wonder if the move online during COVID will be permanent, or if this is actually making people realize how much value they get from interacting with other humans face to face.

Eli Durst, Apple (Meeting), 2016

Jacobs: Over the last several months, you have been shooting a lot of editorial assignments, including a piece about criminal justice in Florida, as well as a profile of Bernie Sanders, for the New York Times Magazine. How do you bring your approach to a more photojournalistic arena? Do you even make a distinction regarding process in your head? Or is it all just one thing: photography?

Durst: It really depends on the assignment. For some, like the story I did about Buc-ee’s for the New York Times, I approach it in the exact same way that I would approach art-making, which makes sense because it’s very much in line with what I’m interested in generally. Other assignments, however, like straightforward portraits, are different. You have to think about the tone and position of the story. I don’t want to just slap a style onto a subject matter or story that doesn’t ask for it. With editorial assignments, you obviously have a lot more restrictions and limitations. I have less directorial control, which is a big part of my art-making—feeling free to change things or move things, or create scenarios in which people have to act or react.

Eli Durst, Brisket Round Up, New Braunfels, Texas, 2019, for the New York Times

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: The photographs in The Community often imply a story, either individually or in sequence, making a viewer consciously or unconsciously extrapolate a narrative that explains how this moment came to be. As your editorial work is usually made to illustrate a written piece, is there room for the abstraction that sometimes flavors the book?

Durst: I hope my images from the Buc-ee’s story have the same, strange, open-ended quality of The Community, but there’s also a photo editor and publication to think of. They have a big say in which photos run, of course.

Eli Durst, Buc-ee the Beaver Statue, Katy, Texas, 2019, for the New York Times

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: The other clear distinction between your editorial work and your more personal work is that, when working for a magazine, you’re beholden to some orientation around truth, and have to, at least loosely, abide by some photojournalistic codes. Do you find this limiting? Do you ever find it tricky to straddle the line between docu-art and docu-journalism?

Durst: Here’s an example: In the book, there’s a photo of a man named Jerry, who I had put on a wig and act out some basic scenarios. When I photographed Jeff Sessions for an assignment, I would have loved to put a wig on him . . . but that was definitely not allowed. You’re restricted by the story but also the realities of access and journalistic ethics in ways that you’re not when making art. I don’t think changing or manipulating a scene necessarily makes a photo less true. In fact, sometimes you can get at things that wouldn’t otherwise be apparent.

Eli Durst: The Community was published by Mörel in spring 2020.