Midcentury Modern in Black and White

Ezra Stoller photographed postwar U.S. architecture with the rigor of a true believer. His images—published widely in numerous trade magazines as well as in House Beautiful and House & Garden—presented modernism not as an avant-garde or utopian vision, but as a movement in situ, one born fully formed like Athena from Zeus’s skull. Yet a global war and an ocean unequivocally separate early twentieth-century experiments undertaken at the Bauhaus and by Le Corbusier from the postwar embrace of modern architecture by corporate leaders and the cultural elite in the United States.

Courtesy the artist/Esto

In Stoller’s crisp, black-and-white prints, boxy-shouldered skyscrapers like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building (1958) or Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s building for Union Carbide (1960), both in New York, proudly rise above the city grid—steel and glass curtain walls towering over masonry edifices. These were depicted as the heroes of a new age. Stoller, always precise about natural light and time of day, photographed Mies’s structure at dusk; every floor is illuminated, and the building seems to glow with industry. His image of New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1959), taken looking straight up into the cylindrical belly of the building, freezes Frank Lloyd Wright’s experiential design of spiraling ramps into an iconic composition—modernism’s dynamism temporarily tamed.

Courtesy the artist/Esto

While civic and commercial architecture have come to define both Stoller’s oeuvre and the heroism of the modern movement in the United States, his archive is full of transparencies showing residential buildings. Throughout his career, he photographed homes designed by architects he was friends with, and those he admired, from Paul Rudolph and Marcel Breuer to Alvar Aalto and Eero Saarinen. Indeed, one of his earliest published images is of the A. C. Koch House (1936) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, designed by the architects Carl Koch and Edward Durell Stone, who taught the evening architecture classes Stoller attended at New York University in the mid-1930s. (He would graduate a few years later with a degree in industrial design and an established photography practice.)

Pierluigi Serraino, author of the recent volume Ezra Stoller: A Photographic History of Modern American Architecture (2019), and Erica Stoller, Stoller’s daughter and director of Esto Photographics, Inc., the company her father founded, both claim that the photographer didn’t change his approach according to building type. “He was extremely studied, each composition was a painting,” says Serraino. Stoller would visit each site and meticulously take notes about the building and the light before setting up a single shot. “His goal was to understand something and explain it,” says his daughter. “He spent a lot of time figuring out the architecture. He believed his pictures were telling the truth.”

Courtesy the artist/Esto

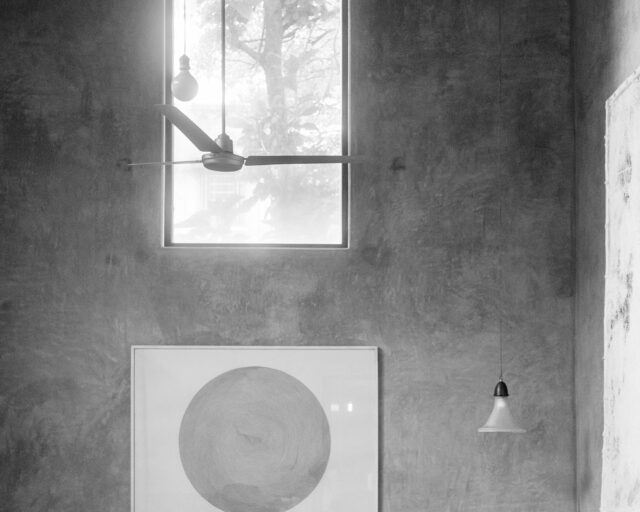

However, the drive toward veracity registers differently when looking at houses and not at the swooping monumentality of Saarinen’s TWA Terminal (1962) or the repetitive efficiency of IBM’s corporate campus (1958) in Rochester, Minnesota. When modernism is performed at the scale of the home, it is personal. Each home signifies a break with the past, a new way to live, the postwar American dream. The architectural photography of Julius Shulman most immediately comes to mind when thinking about mid-century modern residential architecture. His images sell a California lifestyle of improbable vistas and turquoise swimming pools. Stoller’s vérité presents the modern home as attainable, not aspirational. And although Stoller, like Shulman, photographed on the West Coast, most of his commissions were along the Eastern Seaboard, capturing pockets of modernism around Cambridge; Rye, New York; New Canaan, Connecticut; and Sarasota, Florida. That difference in geography, cultural and topographic, points away from the drama of palm trees and blue sky. A forest of tree trunks with bare branches surrounds the Baker Residence (1951) by Minoru Yamasaki, while the interior is full of lush houseplants. A spindly bush nearly dominates Stoller’s photograph of Breuer’s Gilbert Tompkins House (1946), its branches offering a compositional counterpoint to the austerity of the architect’s geometries.

Courtesy the artist/Esto

In many ways, Stoller’s own bootstrapped life encapsulated the American dream he so carefully depicted. The child of Jewish immigrants from Poland, he had an upbringing marked by uncertainty. His father was blacklisted due to union activism, and his mother suffered from depression. The family moved from New York to Chicago and back again, and he went to school in New Jersey, the Bronx, and Manhattan. Success (and his eventual position as gatekeeper) was built through countless magazine and firm assignments and the ability to capture a unity within a space, public or private, even if in real life that cohesion wasn’t quite there.

Such alchemical skill led the architect Philip Johnson to quip that architects wanted their projects “Stollerized.” In 1981, around the time Stoller was winding down his decades-long career, the New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable questioned the very truths of architectural photography central to Stoller’s work. “How much is real and how much is ‘edited’ reality?” she wrote. “At what point do the actual and the ideological merge?”

Courtesy the artist/Esto

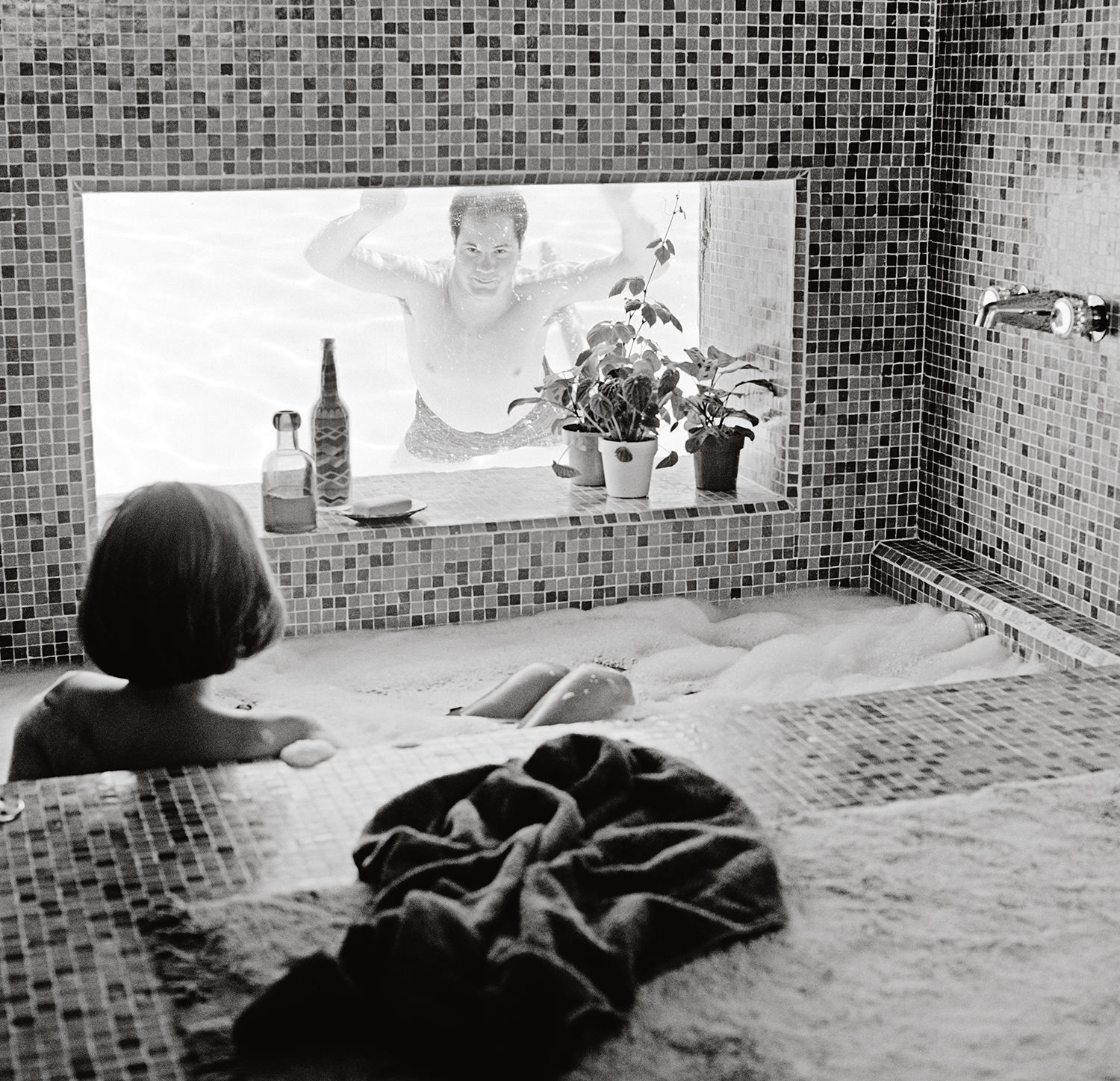

A series from 1949 underscores Huxtable’s query. That year, Stoller photographed his own home in Rye. He had worked closely with the architects Abraham Geller and George Nemeny on the low-slung design clad in vertical timber. The double-height living room, pictured with Eames plywood lounge chairs, a fire in the hearth, and late-afternoon sun casting long shadows across the floor, peddles a modernism that is warm and cozy. In an image of the kitchen, Stoller’s wife, Helen, stands at the stove as two of his children, Erica and Evan, sit at the counter eating from cereal bowls. Erica is in pigtails. In a color version of this photograph, Helen is wearing a bright-red dress and is posed against the white stove and blue countertops. This is the dream manifested.

“The late ’40s was the American moment,” says Erica Stoller. “He had a perfection in mind, especially if you grew up in rental apartments. This is the ideal life cleaned up and controlled.” Her childhood coincided with the exponential growth of her father’s practice, a time when he was capturing the modernist possibilities of other houses, corporate campuses, and high-rises. She recalls that he was always on the road and rarely at home: “The ideal life wasn’t always so ideal.”

Read more from Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.