Elle Pérez’s Havens of Queer Liberation

On dance floors from the Bronx to Baltimore, the artist captures LGBT youth who refuse to be forgotten.

Elle Pérez, Kirsten, 2015

Euforia Latina. Bronx Underground. Autonomous queer spaces now disappeared from the American urban landscape. Rather than have them live on as remnants in the minds of those who found haven there, Elle Pérez insists on their presence. Her photographs are a form of counter-memory, a practice that philosopher Michel Foucault describes as actively reviving the past to resist historical obscurity and narrative death.

Pérez was born the year before Jennie Livingston released Paris Is Burning, a 1990 documentary initially heralded for its provocative characters and its unprecedented exposure of New York’s queer, black, and Latino ballroom culture to mainstream America. In retrospect, what was seen as the film’s innovation can now seem to be racial and class exploitation: Livingston neither turns the camera back onto herself nor turns it over to the stars. “As a twenty-two-year-old from the Bronx watching Paris Is Burning for the first time, it was like falling in love with yourself through a white gaze,” Pérez told me. “That’s what I am fighting against in my work.”

Courtesy the artist

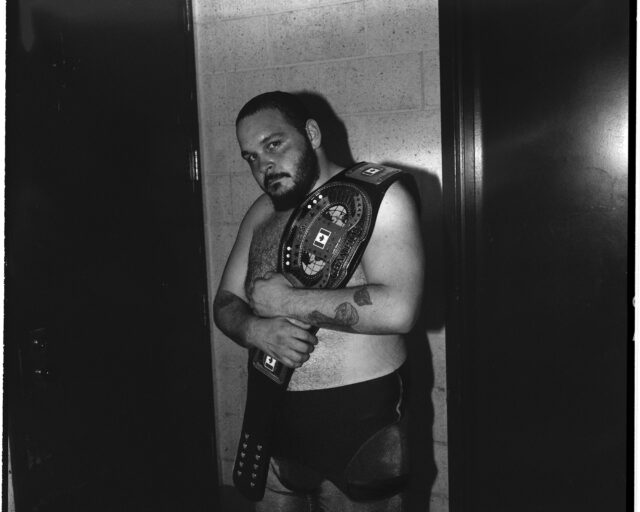

And yet, Pérez’s photographs are more empathetic than embattled. Her close-up shots, a few staged, mostly improvised, capture the offscreen rather than the nightclub’s main attraction. Those moments before the moment. A stairwell before going in or leaving the party. Backstage pageant prep. Peering from behind the curtain. A Selina catsuit hanging midair. A slow inhale. A tight embrace.

That her photographs are from different places might matter for the official record. Some are taken at Euforia Latina, the Latin club night held at Baltimore’s popular Club Hippo, which first opened in 1972. Others are from the Bronx Underground, a punk show hosted at the First Lutheran Church of Throgs Neck, in the Bronx, for fourteen years. Both places permanently closed their doors in 2015, shortly after Pérez captured them for posterity. “In the beginning, I thought I was photographing for the future,” Pérez said. “Because these people would have been left out of the history of punk.”

Courtesy the artist

That her photographs refuse their geographical specificity is the point. These images flatten space, giving us a sense that we are watching both the entertainers and their spectators in media res and waiting for each other. Even more poignantly, Pérez’s black-and-white portraits dislodge these scenes from their respective years of 2014 and 2015 and situate the viewer fully in the present or transport us back to the neopunk scene of the early 2000s or to the roaring Harlem ballrooms of the 1980s. Here, we are all part of an intimate experiment in out-of-timeness in which space and temporality are deconstructed, each moment rendered eternally new.

Pérez’s counterarchive then becomes an alternative to erasure. Taken together, these photographs create their own imagined community, to use the phrase coined by historian Benedict Anderson, in which people are joined by shared experiences or collective memories rather than by the more traditional borders of the nation-state. Unlike the racial and sexual othering in Paris Is Burning, Pérez, working in settings of emotional familiarity, takes her subjects, their queerness, and their blackness and brownness for granted. By doing so, she recenters all LGBT individuals as normative, everyday, and utterly beautiful.

Courtesy the artist

Amid the euphoria and exaltation there is now a stinging sadness as we juxtapose Pérez’s images against the backdrop of those brutally murdered on Latin Night at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub this past June. And while Pulse’s owner defiantly vows to keep its doors open, Pérez’s photographs are their own form of memory-justice, ones that we need now more than ever.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 225, “On Feminism.”