Can a Feminist Embrace Araki?

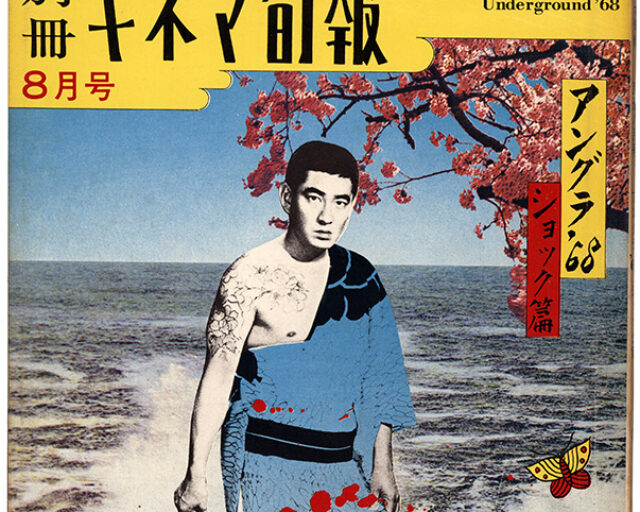

At the Museum of Sex, a new look at the prolific—and provocative—Japanese photographer.

Nobuyoshi Araki, Marvelous Tales of Black Ink (Bokuj ū Kitan) 068, 2007

Being a feminist and an admirer of the work of Nobuyoshi Araki are two viewpoints that do not easily fit well together—especially in our current era of #MeToo. Araki, one of Japan’s most celebrated photographers, is a controversial figure whose work has been derided for its pornographic and sexually demeaning depictions of women. How, then, to reconcile this popular and occasionally apt perception of Araki as misogynistic with a pro-women attitude? Surprisingly, the current Araki retrospective at the Museum of Sex does a lot to address this question.

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Acknowledging this prevalent, mostly Western view of Araki’s photography as sexist and devoid of meaning, the curators at the Museum of Sex have justifiably chosen to frame their exhibition with a direct confrontation of the controversy surrounding his work. Organized by the major themes that have defined the artist’s nearly fifty-year career, The Incomplete Araki covers two floors in a presentation that examines the paradoxes within his copious and consciously branded output. Traveling through the show elicits fluid opinions and conclusions in the viewer, at times seeming to confirm Araki as bluntly misogynistic while at others reframing him as a deeply private sentimentalist. Both perceptions are equally valid when assessing the slippery factual and fictional persona that Araki has cleverly nurtured into “Ararchism”—a portmanteau of “anarchy” and “Araki.

Private Collection

On entering the exhibition on the museum’s second floor, the outspoken, incendiary side of Araki is in full view as one moves down a darkened hallway adorned with rope knots suggestive of kinbaku-bi (Japanese rope bondage art) to confront a lone spot-lit photograph of a suspended, bound kimono-clad woman with her legs splayed, her genitals barely covered by a flower. Conscious of their audience, the curators at the Museum of Sex are literally roping in the viewer’s attention with the most sensational work before slowly unfurling a more nuanced reading of Araki.

Private Collection

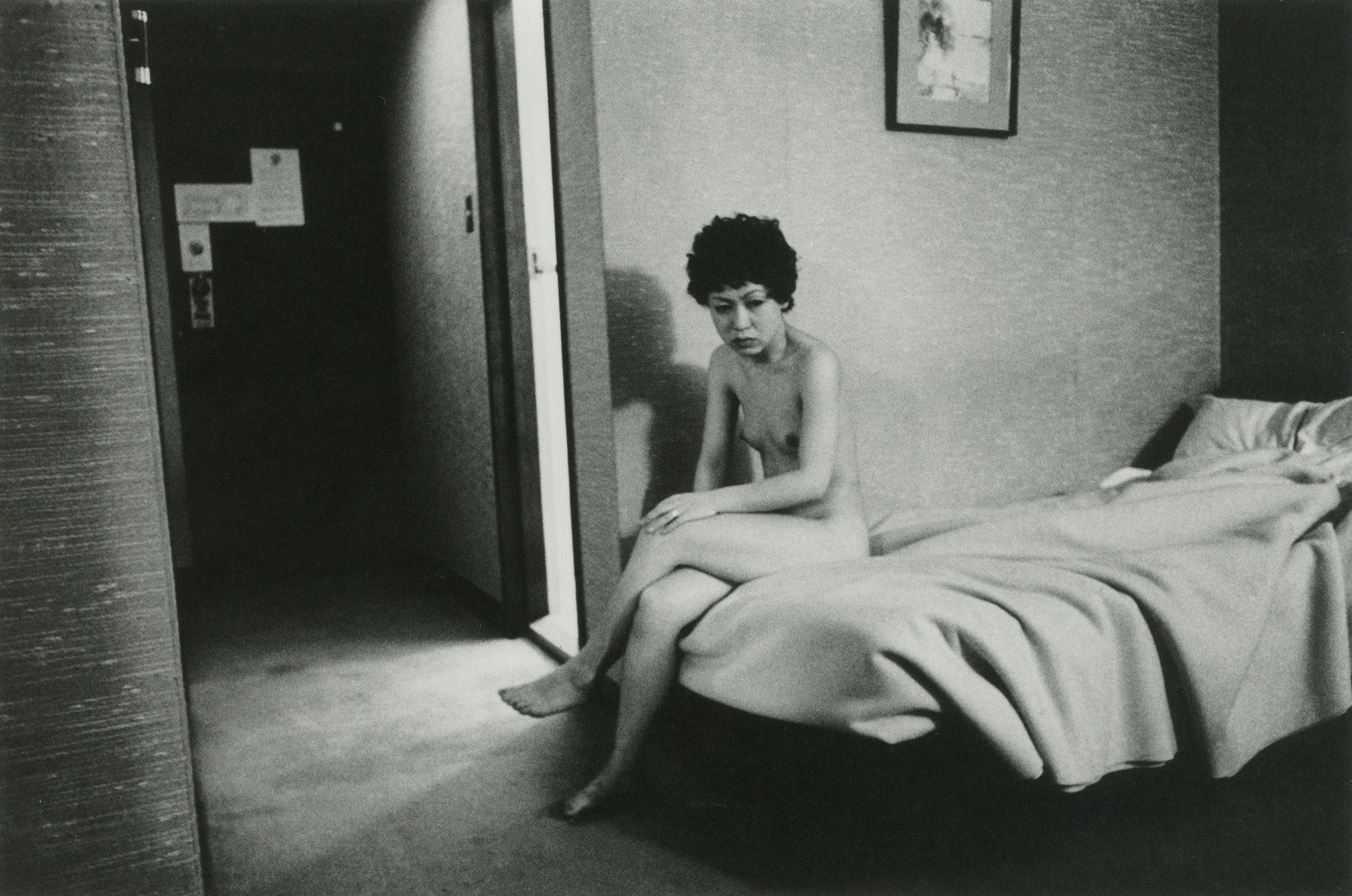

With the initial shock in place, the photographs that follow in the second floor galleries vacillate between large-scale black-and-white and color images of bound women alone, women having sex, models in a studio setting with Araki, and more intimate, date-stamped images that include bound women as well as Tokyo cityscapes, the photographer’s back terrace, his adored cat Chiro, and cloud-filled skies. Expanded wall texts and interspersed video interviews draw attention to the contradictions on display: details on Araki’s relationships with his models (both consensual sexual participation and one anonymous model’s accusation of sexual harassment), notes on his relentless self-branding and cultivated celebrity status, comments on his freewheeling merger of fact and fiction, and a historical explanation of kinbaku-bi are a few of the issues tackled.

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

If exiting the exhibition without continuing to the third floor, the feminist who admires Araki would be inclined toward an overwhelmingly negative evaluation, having gleaned only subtle hints at Araki’s full range. But a signal of what is to come can be found on the last gallery wall of the second floor. Less dramatic than the nudes, but critically important, is a copy, and associated page-turning video, of one of Araki’s early Xerox Photo Album books. Its modest and roughly printed monotone images are juxtaposed on the same wall with similarly unadorned, more personal portrait and landscape prints from his 1995 Endscapes series. Herein lies a key to a broader, more complex reading of Araki that unfolds in its full intensity on the next floor.

Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

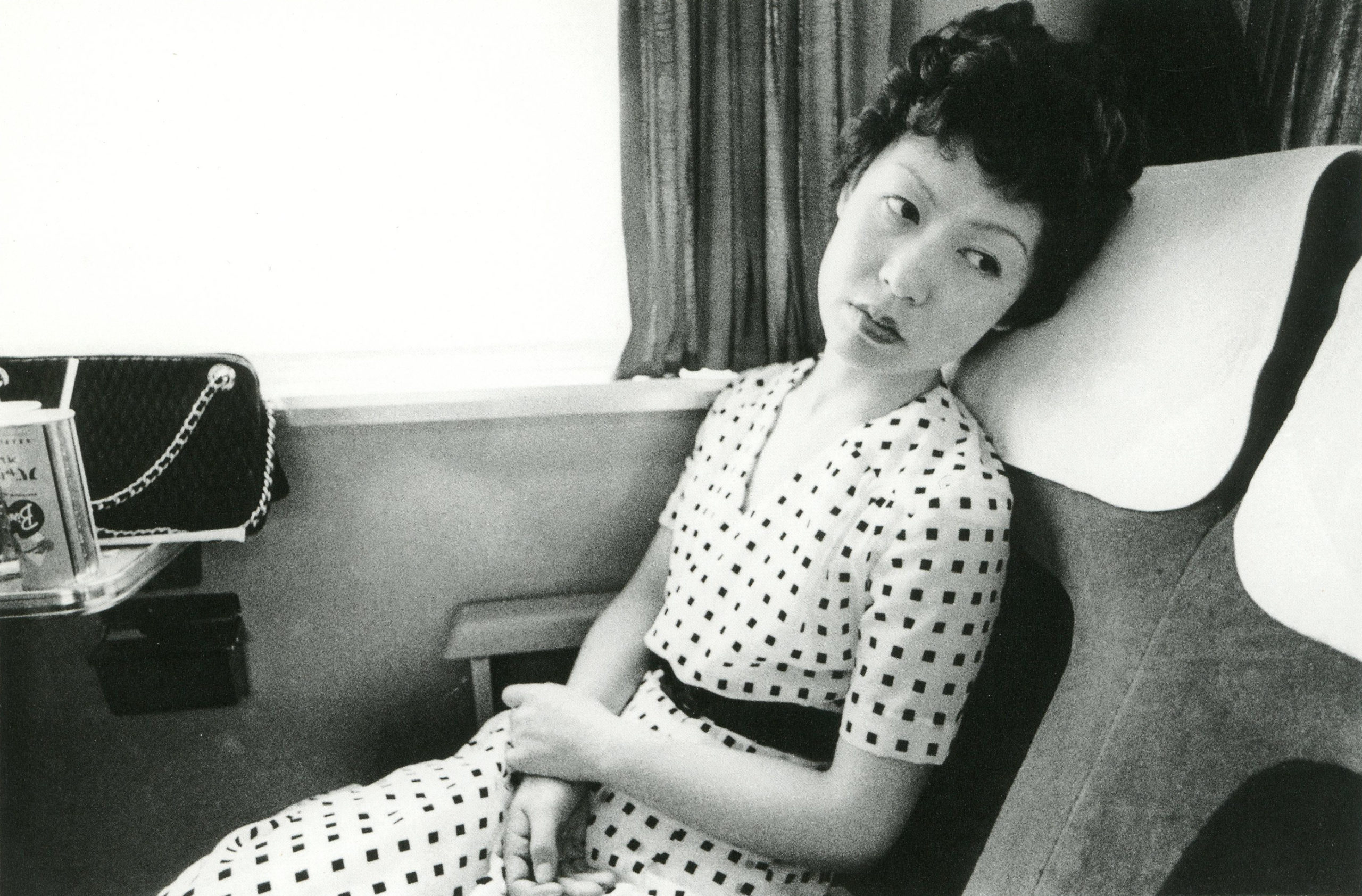

In contrast to the dark and theatrically lit second floor, the upper-floor gallery is awash with an even light that serves to showcase a spectacular room-size case filled with over 450 books from Araki’s prolific photobook production. Presenting the tomes cheek-by-jowl with only their covers visible, the display cleverly includes several interspersed videos of book interiors. The overall impression is a sea of books that covers every stage of Araki’s career, which serves to introduce several of the more introspective thematic obsessions presented on the gallery walls surrounding the case. Foremost is a selection of prints associated with Araki’s Sentimental Journey (1971) and Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey (1991) books, each chronicling an important period in Araki’s tender relationship with his now-deceased wife, Yoko. Black-and-white images of a young Yoko on her honeymoon share the walls with her flower-filled casket—all reflective of the gentle romanticism of a man in love.

Courtesy the Museum of Sex Collection

A less sensational yet still highly sexual perspective is found in the group of Erotos images that examine Araki’s unabashed fixation on the dichotomy of Eros (the impulse toward life and sex) and Thanatos (the impulse toward death). Verging on the abstract, these close-up images of organic and flower forms suggest the sensuality and ephemerality of life without the aggressive sexuality found in the bondage photographs. A curatorial pairing of sexually brazen nineteenth-century ukiyo-e woodblock prints—one with specific references to kinbaku-bi—next to staged photographs of bound women provides further analysis of Araki’s contradictory forces. As Araki observes, “Photography, in a way, is a modern ukiyo-e.” However, he is quick to point out that he likes to take photographs similar to shunga (erotic ukiyo-e), but has yet to reach that level of mastery.

Private Collection

Paradoxes and obsessions shape Araki’s world, which blurs the boundaries between respectful depictions of women and pornography. Whether presenting a spectacularly lit photograph of a bound woman, a group scene of drunken, sexualized debauchery at Tokyo Lucky Hole (Araki’s favorite bar in Shinjuku’s Kabukicho district), or a tender photograph of his late wife, Araki is a complex persona and artist who should be more fully explored in the U.S. beyond his provocative, audience-arousing bondage photographs. The Museum of Sex is apparently the only institution in the U.S. willing to take on this challenge. As a retrospective, The Incomplete Araki is indeed incomplete—as any retrospective of his would be, given his immense output—but it is nevertheless a window into a fascinating artist. While the exhibition lures visitors with the more provocative and titillating photographs, its lasting imprint dispels many of the one-dimensional viewpoints that otherwise keep Araki’s work from being embraced by a broader audience.

The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Works of Nobuyoshi Araki is on view at the Museum of Sex, New York, through August 31, 2018.