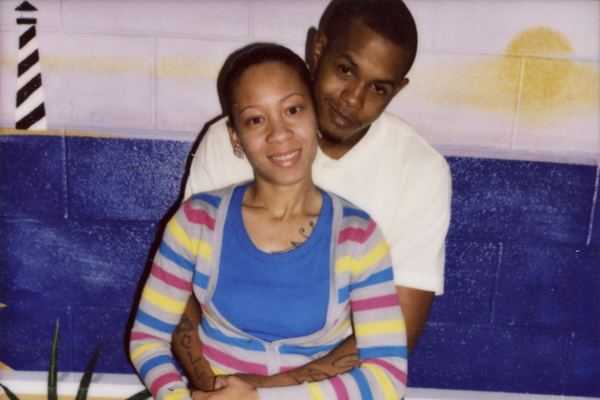

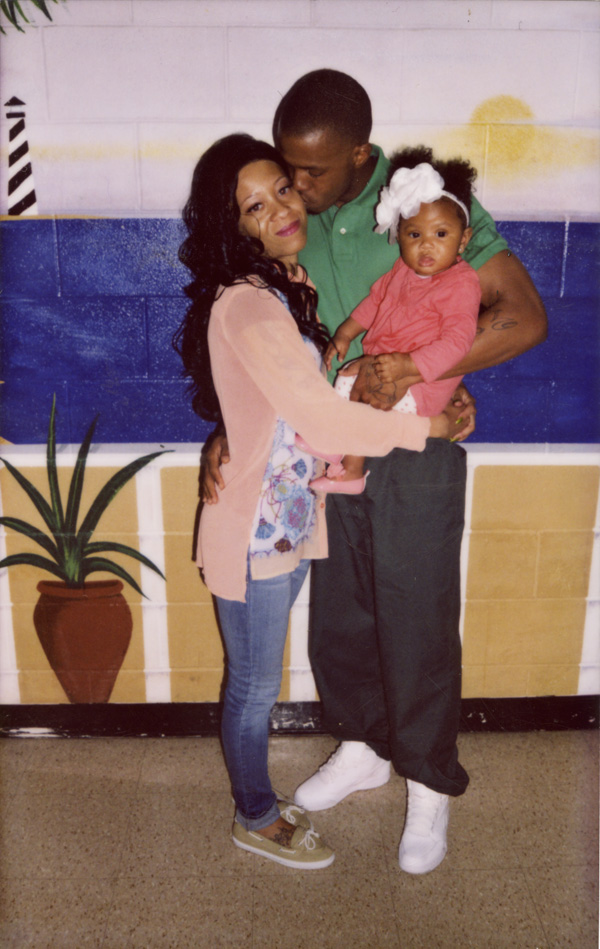

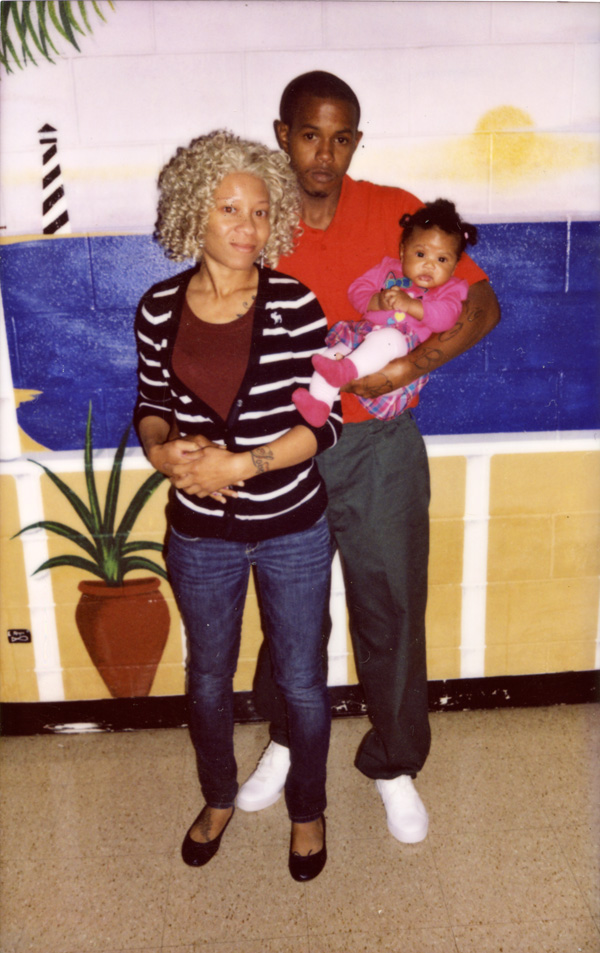

Deana Lawson, Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family, 2012–14

One of the most voluminous sites for the production of contemporary black photography takes place in the visiting room of U.S. prisons. Makeshift photographic studios exist in jails and prisons across the nation and are an important, often the primary, arena for documenting incarcerated people and the loved ones—mothers, spouses, lovers, children, sibling, childhood friends—who visit them. Generally, prison photo studios are provisional spaces in the visiting room, or a waiting area, and are operated by incarcerated men and women whose job in prison is to serve as studio photographer. The studios are typically located near the guard booth and remain under the watchful eye of prison staff who monitor for suspicious activity, such as exchanging confiscated material or engaging in “inappropriate” physical contact.

In Deana Lawson’s series Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family (2012–14), we see the power of prison studio portraits to document familial and intimate attachments for black Americans, who are disproportionately impacted by mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex. Lawson’s images, which she appropriated from photographs originally taken by a prison photographer, document her cousin Jazmin’s visits to her partner, Erik, who was incarcerated at Mohawk Correctional Facility in Rome, New York. In some of the photographs, Jazmin and Erik hold each other affectionately. They kiss and hug. In others, they stand together as a family with their young children in the frame. The composition of these portraits follows the tradition of family portraiture in which the patriarch stands at center with wife, or maternal figure, and children at his side. Keeping in line with conventions of the genre, prison portraits also incorporate fantasy backdrops, which are often painted by incarcerated artists.

Taken together, prison portraits become a powerful archive representing the enduring struggles of black Americans to claim citizenship, kinship, love, and even hope in the face of multiple forms of racial injustice—poverty, profiling, failed economic policies, and mass incarceration. They also document important forms of self-expression for the many millions who have been locked away and whose images and profiles are otherwise strictly managed by bureaucracies enforcing criminalization and incarceration. Moreover, prison portraits, which are often sent between incarcerated and non-incarcerated loved ones, are important material objects to maintain connection and to communicate love in some of the most dire and punitive conditions, that is, the modern U.S. prison system.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.