For Bertien van Manen, Photography Was All About the Heart

In her unvarnished portraits of strangers and family, the late photographer extolled the beauty and mysteries of everyday life.

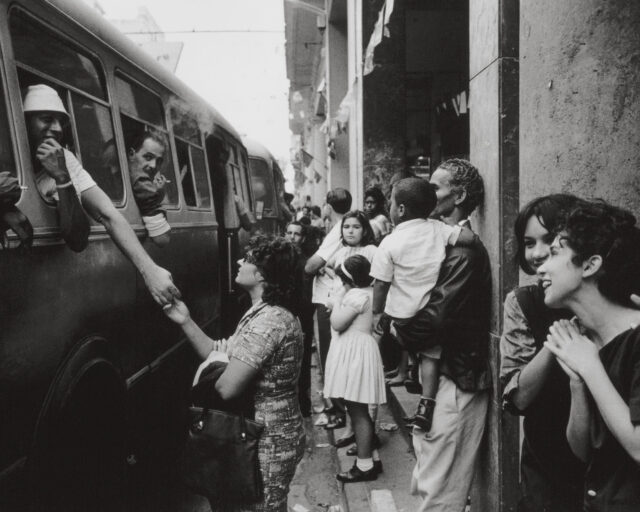

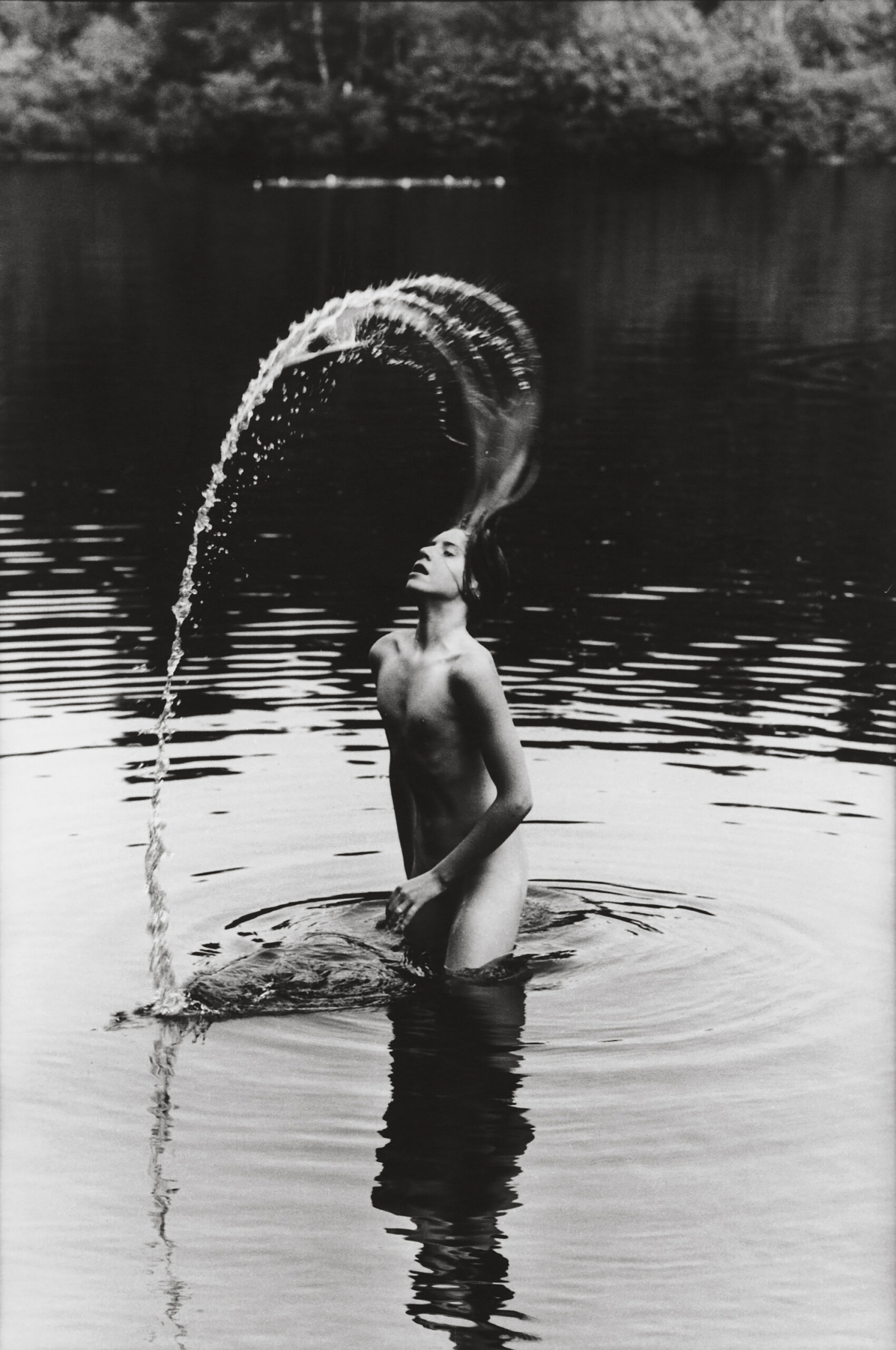

Bertien van Manen, Kendra, Kentucky, 2007, from the series Moonshine

This interview was originally published in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” Fall 2015.

Born in 1942, Bertien van Manen began her career in the 1970s as a fashion photographer. Commercial photography, however, soon left her wanting and unfulfilled; like many photographers of her generation, inspired by Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), she subsequently shifted toward an expressive and intimate documentary approach. Some of her earliest work addressed the lives of immigrant women in her home country, the Netherlands, and the curiosity that motivated that work prompted her to explore communities all over the world, from bootleggers in Appalachia to villagers in the former Soviet Union, for books including A hundred summers, a hundred winters (1994); East Wind West Wind (2001); Let’s sit down before we go (2011); Easter and Oak Trees (2013); and Moonshine (2014). Her photographs, made on trips throughout Eastern Europe, Russia, Asia, the United States, and, most recently, Ireland, often focus on the human experience of undertaking a journey.

Although van Manen’s work has been exhibited in many of the world’s leading museums and is held in major collections, she remained something of a photographer’s photographer. Of her unique snapshot sensibility, the Swedish photographer JH Engström notes: “If I’m distracted by all the photography out in the world, Bertien’s work reminds me that photography is all about the heart.”

On the occasion of Manen’s death on May 26, 2024, we revisit the photographer’s conversation with Kim Knoppers for Aperture’s “Interview Issue” in 2015. Knoppers, curator at Foam, Amsterdam, visited van Manen at her home studio, located on the third floor of a classic canal house on Amsterdam’s Keizersgracht, for a conversation about the path of her well-traveled career and what it means for her to revisit older bodies of work, including her mid-1970s Budapest photographs, which will form her next book project. —The Editors, 2024

Kim Knoppers: You began making photographs in 1973, after you graduated from university, when you had a family with two small children. Why did you feel the urge to change tack?

Bertien van Manen: I’d done a lot of translation work and taught French, but I was continually at home. I wanted to get outside. While studying French at the University of Leiden, I worked as a model for a while. I lost interest in that and thought, I’ll turn things around—I’m going to get behind the camera instead of being in front of it. That’s when I started photographing my children.

We had a party at our house, and the fashion and advertising photographer Theo Noort was one of the guests. He saw my photographs and asked me to be his assistant. Later, I worked at an advertising studio in Amsterdam. I knew nothing about photography or how to develop film. I learned all that from Noort and the studio.

Knoppers: How did you end up as an independent fashion photographer?

Van Manen: I first earned money as a photographer for the Dutch women’s magazine Viva. There, I photographed Sylvia Kristel [the stylish star of the 1974 soft-core porn film Emmanuelle, one of the first erotic films to be released worldwide by a big Hollywood studio]. The story making the rounds in the Amsterdam bars was that at the age of sixteen Kristel had announced, “You wait and see: I’m going to be famous.” She did a great deal to make that come true [laughs]. Kristel appeared in the first soft-core porn film and was naked all the time. I was one of few female photographers in fashion in Amsterdam. The models appreciated working with a woman instead of all those guys. They felt freer and less like objects of desire. So I had an astonishing amount of work.

Knoppers: Why did you leave fashion again, this time as a photographer?

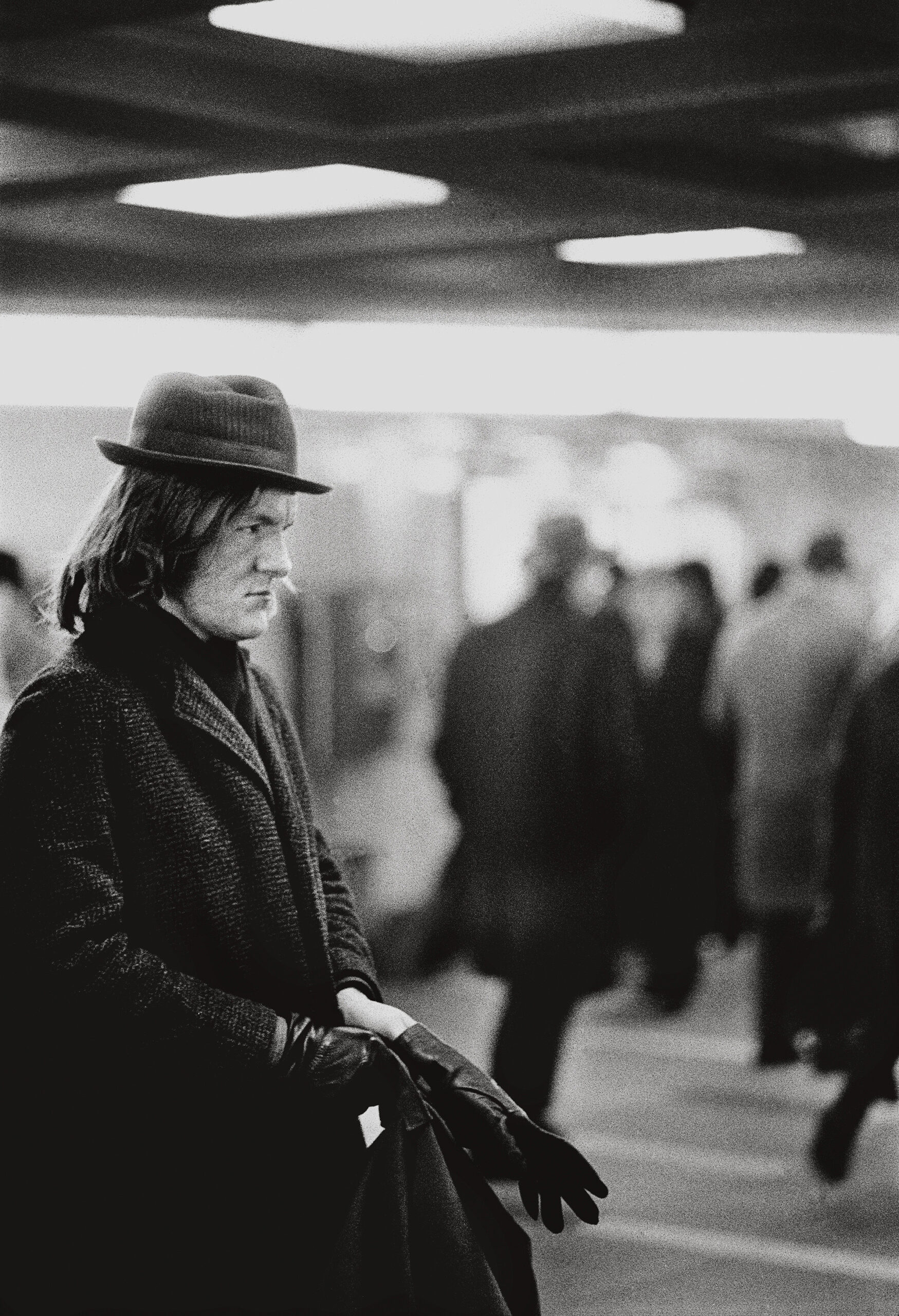

Van Manen: In 1975, the photographer Kenneth Hope showed me The Americans by Robert Frank, and everything changed. How can you capture in words what he does? He wasn’t at all in the business of making beautiful photographs, yet that’s what they are. The coincidental, the inadvertent—I thought his photographs were magnificent. The roughness of his work and the absence of the spectacular appealed to me enormously. I immediately wanted to travel. The children were slightly older and I had the romantic idea to go to Budapest in the mid-’70s. It was such an old, baroque city that was then behind the Iron Curtain. I have showed the pictures I made there only twice: at the former Institut Néerlandais, in Paris, and in the magazine Street Life, the British equivalent of Rolling Stone. At the moment, I am revisiting this work.

Around this time, I burned my bridges at Viva because I was fed up with fashion—it was hollow— and went to work for Avenue, Nieuwe Revu, and Panorama. [Avenue was a Dutch fashion magazine inspired by Vogue, moving between popular and elite culture. Renowned writers and photographers were associated with it, such as W.F. Hermans, Cees Nooteboom, and Ed van der Elsken. In the 1970s Nieuwe Revu steered a left-wing, rebellious course perhaps best encapsulated as “socialism, sex, and sensation.” Both Nieuwe Revu and Panorama are part of a strong Dutch tradition of social reportage.] But I was not very connected to the editors of these magazines. I took my photographs and delivered them. I felt more attached to the scene around the leftist publication De Groene Amsterdammer. Photography in this magazine was actually marginal, but the editor in chief was impressed by my Budapest work and from that moment I worked regularly for him. This was toward the end of the ’70s and the early ’80s. Photography became more important for De Groene Amsterdammer, and Dutch photographers like Hans Aarsman, Taco Anema, and Han Singels were involved. Everyone who was left-oriented started at De Groene Amsterdammer. We had a good time at the office. Once I was asked to take a photograph of the editorial team behind their desks without clothes. I traveled with the Dutch writer Geert Mak to the United States to portray leftist Americans. We had to find them with a lantern [a Dutch expression].

Knoppers: What led you to embark on your first long-term, self-initiated project, Vrouwen te Gast (Women who are guests), in 1979?

Van Manen: I had had enough of the hectic life of working for magazines. I wanted to have more time to make less superficial photographs. I saw the 1975 book A Seventh Man: Migrant Workers in Europe by John Berger, which portrays the lives of guest workers. There are photographs in it by Swiss photographer Jean Mohr, Berger’s frequent collaborator. It remains relevant because the tension and effects of migrant labor are still major issues in Europe today. The introduction stated that unfortunately they hadn’t gotten around to documenting the women. No wonder, since it was made by two men! They hadn’t even made it through the door with the Muslim women.

That’s my subject, I thought, and in 1979 I started working on Vrouwen te Gast. I didn’t just photograph women who’d joined their husbands but also single women who’d come to the Netherlands to work. Suddenly those rural women were shut up alone in a tiny backroom apartment, unable to speak the language, and they sat there languishing behind closed curtains. I decided to group the women according to their countries of origin: Turkey, Italy, Spain, Morocco, Yugoslavia, Tunisia, Portugal, and Greece.

Knoppers: How did you manage to get into those women’s homes?

Van Manen: There were plenty of community centers for male immigrant guest workers. One center organized sewing lessons for their women. They helped me. The Muslim men wouldn’t let their wives be photographed casually in the house; for them an “official portrait” was enough. In the end the combination of posed and more spontaneous photographs worked well.

The book was published by the feminist publishing house Sara in Amsterdam. I had to spend a full day there defending the order of my edit in front of a collective of eight women. Ultimately I persuaded them that my edit was best. In the last paragraph of my text for the book, I noted that the Dutch women’s movement had done nothing for immigrant women. The book was a success because it got all sorts of things started for these women who were invisible and to whom no one had ever paid any attention before. It really had an impact. Dutch language courses for women were organized. Neighbors went to visit the women in their homes. The immigrant women came out of isolation.

Knoppers: Did you consider expanding the project to other countries?

Van Manen: Along with photographer Catrien Ariëns, I was commissioned by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam to photograph the women’s movement in the Netherlands. Eva Besnyö [Dutch-Hungarian photographer, 1910–2003] rang me. They’d asked her first but she was unavailable. I felt honored and let myself be persuaded. But I’m not particularly proud of the book that came out of it. The texts are unbearable. For example, one of them explains what kind of ailments you get during menopause. I found myself in yet another of those halls full of gray-haired women in dungarees. Absolutely not photogenic.

Knoppers: Do you regard the early period of your work as a learning process in which you grew and reached full maturity with A hundred summers, a hundred winters [photographs taken between 1990 and 1994 in Russia]?

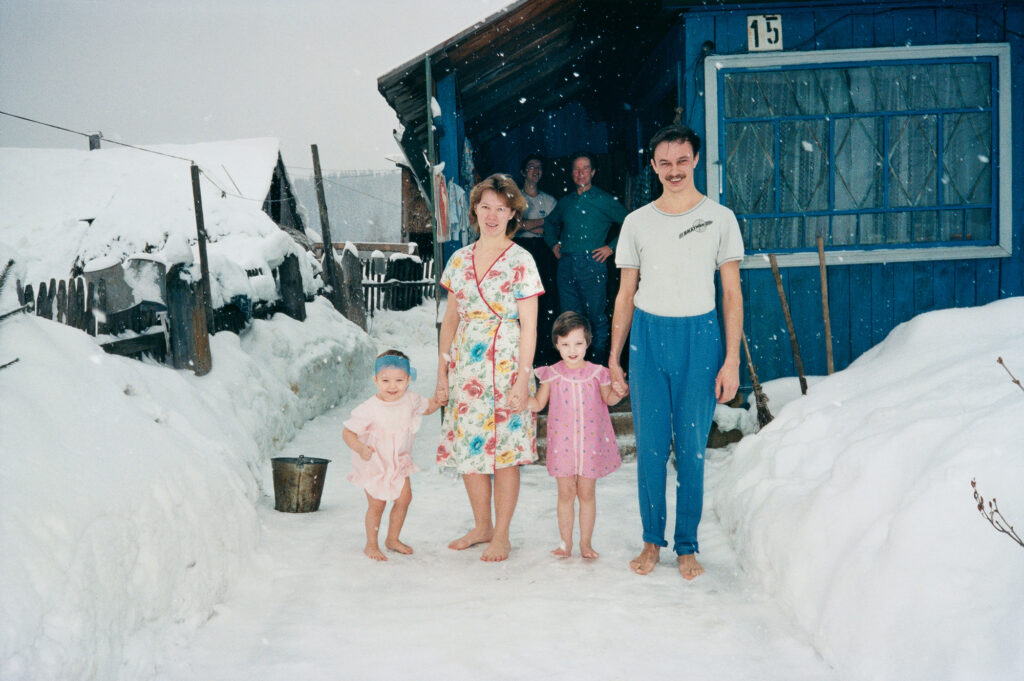

Van Manen: Yes, although there are also some really good photographs in Vrouwen te Gast. For A hundred summers, a hundred winters I started in black and white. But that didn’t work. Cartier-Bresson, and I don’t know how many others, had made nostalgic black-and-white photographs in Russia, but I found the colors there so extraordinary.

The colors of our Western clothing were synthetic, whereas there they were still making dyes from plants and flowers. The decision to photograph in color was extremely important.

Knoppers: How was it that you ended up in Russia?

Van Manen: I’d wanted to go to Russia for a very long time. My grandfather lived in a big house on a country estate in North Brabant, and there his relations from Poland and Russia would visit him regularly. One of them I was told to call Uncle Eugène, but he was really a cousin. As a little girl I found Uncle Eugène unbelievably exciting. That must have had something to do with it, unconsciously. In 1982 I went to Poland to make an editorial for Vrij Nederland [a Dutch magazine] about women living behind the Iron Curtain. I went with a philosopher of Polish descent who wrote the article. It was exciting because we brought fifty IUDs from a friend of my husband’s who was a gynecologist. Women used medieval methods for birth control, like foam tablets. I must have a photograph of the small factory where they made these foam tablets. We were caught at the border, but after giving the customs official one of the IUDs for his wife, he let us enter Poland. The Russian influence there was huge, of course. In 1987 I traveled to Russia for the first time with a communist journalist from the British paper the Morning Star. By then I’d taken a course in Russian and could speak the language a little. We went to Donetsk, in eastern Ukraine, where there’s so much conflict now, a coal-mining region. I was keen to photograph the miners.

I didn’t succeed in Donetsk. The union, which was heavily controlled by the communist government, arranged for a beautiful table with a white cloth and a buffet of Russian food at a woman’s house, and behind it stood a lady in traditional costume. It was a tourist attraction. One evening I literally broke out—I escaped from the people who were looking after me, the guards. During this time, the union was strongly orthodox and people were not allowed to talk to foreigners. I went and stood on the street and stuck up my hand. A car stopped and I said to the man at the wheel, “I want to go to where the shakhtery, the mineworkers, live.” He took me there. But they weren’t allowed to talk to foreigners, unfortunately.

I returned to Russia in 1989, to Moscow, to polish my Russian. My teacher asked if I’d like to come and live with his family. They had a spare room and it was a way for them to earn a little extra money. So that’s what I did. He lived there with his parents. I stayed in his house for several weeks. In total I went back fourteen times and traveled through Russia, Moldavia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Tatarstan, and Georgia. I always stayed in the houses of local people who became friends. I wanted to grasp the beauty and the mystery of daily life. “I haven’t seen you for a hundred summers, a hundred winters”—that’s what people in Russia say when they haven’t seen each other for a long time. It became the title of my book.

Knoppers: The people in your photographs seem to forget they’re being photographed. No doubt that has to do with the amateur compact cameras you use.

Van Manen: I started off working with Leicas and Nikons, but one day they were stolen from my house in Amsterdam. I took compact cameras but with good lenses with me because it was safer. They were just little toys, so they didn’t get stolen. People felt less threatened by them, anyhow. You’re with a guest who also takes photos, rather than with a photographer who’s your guest. I could leave them lying on the table and I always had about three of them with me. Sometimes people would start using the little cameras themselves. I was staying with Irina, who has since then become a good friend, and her aunt, and there were two boys of about ten. I arrived home in Amsterdam and looked at the contacts and thought: Was I so very drunk? Did I really make photos like that? Then I realized that the boys had been photographing each other, with bare bottoms and in other funny poses. Even the photograph of the little boy on top of the wardrobe that ended up in Let’s sit down before we go was made by them.

Knoppers: I find it extraordinary that you can get so close to people without making the observer of the book feel like a voyeur. Is that something you make a conscious effort to achieve or is it intuitive?

Van Manen: I’m always terrified I’m bothering people, and that they won’t like me.

Knoppers: That’s difficult, considering the kind of photographs you make, but it’s probably also your strength.

Van Manen: Yes, but sometimes the things I haven’t done keep me awake at night. I was brought up in a very Catholic environment, of course, and I’m totally fascinated by all those Russian Orthodox churches. One day I heard music coming out of a church in the countryside. I went in and saw the priest standing there. All the women were on their knees in a line in front of him. My god, I didn’t dare photograph that. I’m fearful of everything that has to do with the church.

Knoppers: The Polish journalist Ryszard Kapus ́cin ́ski wrote the foreword to A hundred summers, a hundred winters. How did that come about?

Van Manen: Joseph Brodsky [the Russian-American writer] was supposed to write the foreword. He visited me here in Amsterdam and it was great to see how enthusiastic he was, but he fell ill and died. Kapus ́cin ́ski had written a book called The Emperor (1978), which I found tremendous. Not a bad replacement, but it’s still a shame.

Knoppers: You said that your fascination with Russia is very personal. After the publication of A hundred summers, a hundred winters, you went to China to work on your next big project, East Wind West Wind [photographs made between 1997 and 2000]. Was there a similar personal link with China

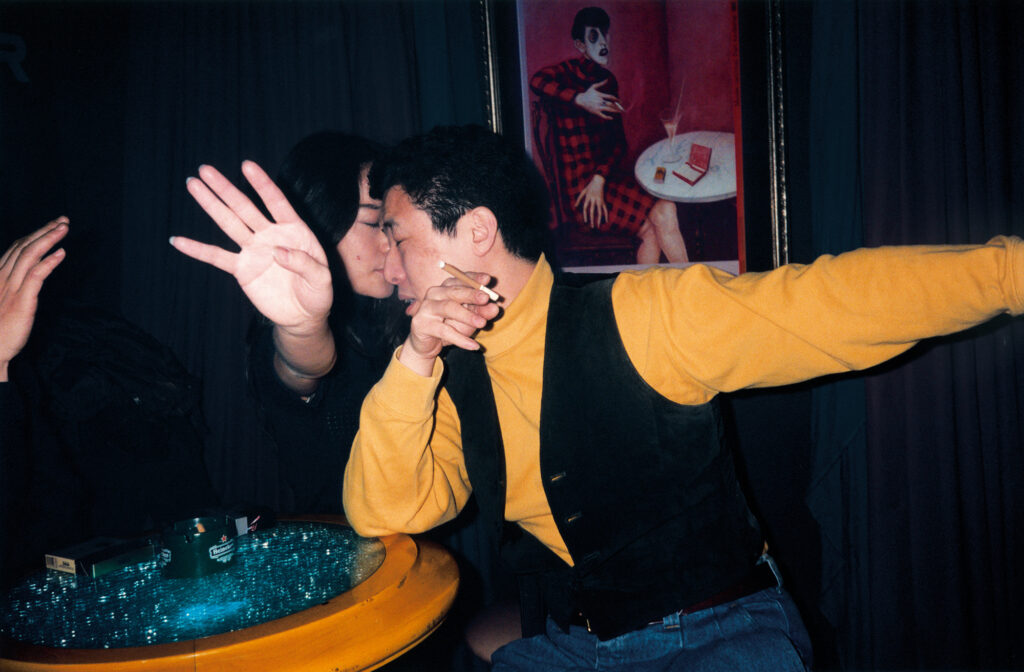

My attention was turned in that direction by Paul Wombell, who at the time was director of the Photographers’ Gallery in London. He was in Amsterdam and he invited me to put together an exhibition at his gallery, but I was in a black hole. A hundred summers, a hundred winters had been so intense. He suggested I should go to China because the country was changing so much. I went there ten times before I finally knew what I was looking for. I traveled to both the major cities in the east and south, as well as rural village in the west, wanting to depict the daily life of common Chinese people. I always came back with beautiful calendar pictures, but that wasn’t what I was after. The tenth time I was with my friend Xiao Feng at his friend’s home, an apartment on the twentieth floor in the city of Chongqing. We’d been inside all day. In the late afternoon we went out. We got onto the street and the heat, the crowds, and all those voices came flying at me. There was a buzz all around me. Suddenly I knew that I wanted to capture that vibrant feeling. I immediately started photographing things that at first you may not realize can be truly magnificent. One photograph was taken in a small movie theater where movies were shown twenty-four hours a day. Young people escaped their domestic environments and the gaze of their parents by going there.

Knoppers: All your books, with the exception of Easter and Oak Trees, which features black-and-white photographs of your family taken between 1970 and 1980, are set in areas and communities that are fairly closed.

Van Manen: In Siberia I walked through a village and people came out of their houses to greet me and invited me in for a cup of tea. In China, in a small town in the north, they announced through the town’s loudspeakers that a foreigner was around. “There’s a white woman who looks different. She’s a person too, just like us. Leave her in peace and don’t touch her.” My guide translated it for me. I thought that was fantastic.

Knoppers: For Let’s sit down before we go [photographs taken in Russia between 1991 and 2009] you asked the photographer Stephen Gill to go through all the contact sheets from your Russia archive. Why did you desire to look back?

Van Manen: I kept coming upon photographs and thinking, Why isn’t this in the book? There turned out to be far more intriguing photos than I’d expected. Of course I couldn’t be sure, because they’re my own photographs. So I asked Stephen. The expression “Let’s sit down before we go” comes from the Orthodox Church. People would kneel for a moment to pray before starting out on long journeys with horses and carts, because there were all kinds of dangers along the way, such as wolves and Siberian snow. It’s still the custom, but now they do it quickly as a kind of ritual. [Van Manen demonstrates, briefly sitting down and then getting up again.] I thought it was a good title for a project in which I too sit down and go through my archive. A moment of reflection.

Knoppers: The photographs in Let’s sit down before we go were made in the same period as A hundred summers, a hundred winters, but they’re very different in style. Why is that?

Van Manen: Stephen Gill and I paid attention to different things in the editing. Twenty years had passed since I took the photographs. A development had taken place in photography and in myself. This book is far freer than A hundred summers, a hundred winters. At that time certain things weren’t “allowed.” The Robert Frank method was far from accepted by everyone in those days. Nothing was supposed to be in the picture that didn’t “belong” there. Everything had to be neatly within the frame. Overexposure was a mortal sin. But overexposure produces a strange and exciting effect. In Let’s sit down before we go imperfections became a unifying theme.

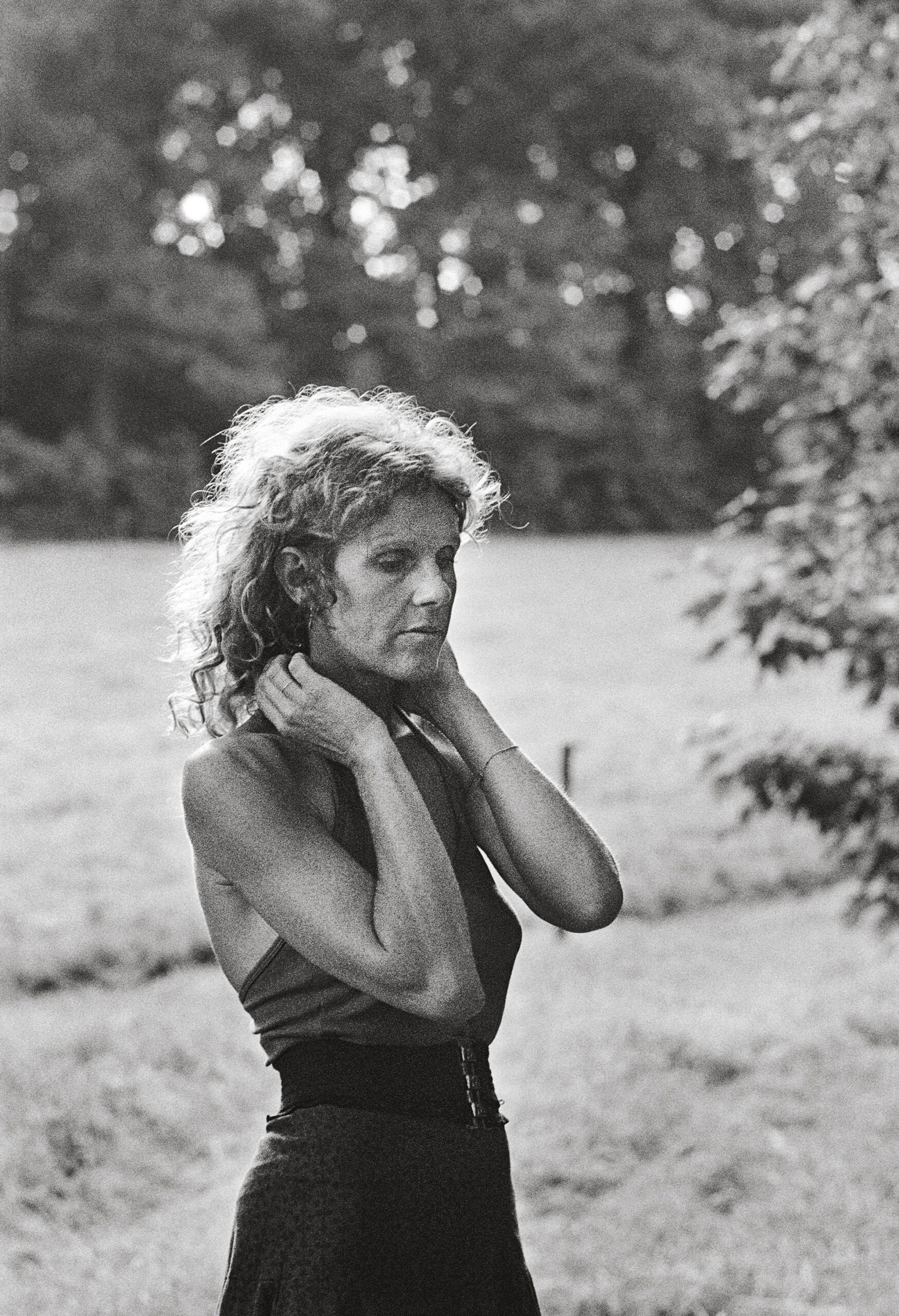

Knoppers: You always get very close to other people. And you’ve said that you sometimes have difficulty with that, with taking such intimate pictures. Easter and Oak Trees is based on family photographs from your archive. You reveal yourself and your family during intimate, private moments. What is the setting for Easter and Oak Trees?

Van Manen: At Easter I usually went with my family to my grandfather’s large country estate in the province of North Brabant. We have a favorite Joe Cocker song in the family, on the record Mad Dogs & Englishmen. At one point Joe Cocker says, “This izzzz Easter.” He can say that really beautifully. And the estate is full of oak trees.

Knoppers: Have you asked your children, now adults, what they think of the book?

Van Manen: They think it’s beautiful, but they have mixed feelings about some of the photographs.

Knoppers: Do you often find that people who end up in your books are ultimately shocked by how they appear?

Van Manen: People look so differently at themselves than the way I look at them. That’s why it’s often difficult when you send them the photographs. I think they look great, but there’s always something wrong with their figure or with their chin. Nowadays, of course, there are so many opportunities to photograph yourself. Everyone makes some kind of glamour photograph so that they’re shown to the best possible advantage and can direct every aspect. Those are of course very different types of photographs than the ones I make.

Knoppers: Moonshine, your most recent project with MACK, is about mineworkers’ families that you visited between 1985 and 2013 in the Appalachian Mountains in Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia. Before that, you tried to get in touch with mineworkers in Donetsk. Why are you so interested in mining communities?

Van Manen: I grew up in the mining region of Heerlen, in the south of the Netherlands. My father worked at the state mines and I attended a local Catholic school where I was surrounded by miners’ daughters. I often visited their homes and I loved it there. At my friends’ houses everything happened in a little room where the windows were steamed up from soup on the stove. The mothers fascinated me. I found it so cozy there. At our place it was all a bit colder. I felt far more at home with those mineworkers’ families. Also, my very first photography project was on miners in a little mining village in West Yorkshire, UK, called New Sharlston.

Knoppers: For the last year and a half you have been photographing in Ireland. Do you have the feeling that you’ve already found what you’re looking for there?

Van Manen: Actually, I do, though I go back to perfect it and to have more material to choose from.

All photographs courtesy Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Knoppers: That’s relatively quick compared with your other projects. Why do you think that might be?

Van Manen: For my other projects I photographed people in their own environment. That was my great fascination. In Ireland I dispensed with the people and reflected more on the atmosphere and on the death of my husband Willem. He died seven years ago. I photograph the Irish west coast a great deal: It is the end of Europe, the end of the world. It’s about endlessness, about ruin and death. It’s poetic and mythical.

At the moment I’m reading everything I can get my hands on about Ireland. Much of the literature from Ireland is about families with lots of children, steamy relationships, Catholicism, a father who drinks and tyrannizes and lashes out. The mother is kind and cares for the children. There are of course beautiful lines about nature, by novelists like John McGahern, or about the sea, by John Banville. Or by poets like Michael Longley, with his poetic everyday directness, or Seamus Heaney, whose poems sometimes are mythical and go back to anonymous early Irish lyrics. But I also read a lot of French and German literature. There’s now a little French bookshop two streets away from me and it’s wonderful. I need literature when I’m traveling. Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Bulgakov, Gogol—all those magnificent Russian books. They’ve all become friends of mine.

Translated from the Dutch by Liz Waters.

This interview was originally published in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” Fall 2015.