At FotoFocus, the Radical Notion That Women Are People

Are we living in a state of emergency feminism?

Jeffrey Brandsted, Brick x Brick at D.C. Women’s March, 2017

Courtesy of FotoFocus

Two weeks before the Women’s March on January 21, 2017, Sara Vance Waddell posted a message on Facebook asking marchers to save their protest signs. Vance, a philanthropist who primarily collects art made by female-identified artists, wanted to make an exhibition of artwork from the march at the gallery in her home in Cincinnati, Ohio. When the signs that protesters sent began piling up, Waddell realized she had a bigger project on her hands. Like many Americans, prior to the 2016 presidential election, Waddell hadn’t thought of herself as an activist. But suddenly it was clear, as one participant wrote in thick black ink on a cardboard placard, that “The Future is Nasty.”

Are we living in a moment of emergency feminism? Among the gathering of artists, critics, scholars, and cultural workers at the FotoFocus symposium “Second Century: Photography, Feminism, Politics,” presented in Cincinnati in October, there was a mood of enlivened solidarity, a sense that if you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention. The symposium opened with a panel discussion by FemFour, the group that Waddell assembled to turn her Women’s March project into a traveling exhibition, but the subsequent panel discussions and keynote addresses often took on the energy of a teach-in. Although the FemFour’s project is not concerned specifically with photography, their discussion seemed an appropriate way to open FotoFocus. For curator Maria Seda-Reeder, who worked with Waddell to assemble the collection, the Women’s March project had an emotional dimension. In working with FemFour, she had connected to other women who were also “mad as hell.”

Courtesy of FotoFocus

They might have been mad, but many of these women produced witty signs, ingenious sculptures, works on paper, T-shirts, pins, and, of course, knitted “pussy hats,” examples of which were hung on walls and laid out beneath glass at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center in FemFour’s Still They Persist: Protest Art from the 2017 Women’s Marches. Seda-Reeder called the exhibition a “living archive,” yet at the venue, the posters looked like sacred objects. Now in a collection, these souvenirs made from humble materials are protected for posterity: they’re physical evidence of a moment widely documented in photography, on social media, and across the news. It was disarming to see signs reading “#yuge mistake” and “NOW YOU’VE PISSED OFF GRANDMA”—which might otherwise have been swept into trash piles in any number of cities around the country—neatly hung in rows in the sanctum of a white-box gallery space. Still They Persist appears to be a rejoinder to that perennial protest chant: this is what democracy looks like. Or looked like, in 2017.

The title for this edition of FotoFocus, “Second Century,” was a nod to Simone de Beauvoir’s germinal book The Second Sex, from 1949, and was meant to gesture to the next century of feminist struggles—notably those at the confluence of women’s rights, immigration, health care, LGBT equality, and racial justice—and how photography might become a visual vanguard. It’s a tall order. “Second Century” swerved across disciplines and opened up a critical space for dialogue around feminist cultural work. Panelists addressed painting, video, digital platforms, the women pioneers of Latin American film, midcentury archives of color photography, and the American Dream in images of baseball players and cross-country drifters. Pointedly, the possibilities of urgent feminist action—in art and culture, and by extension in politics—were never distant from the conversation.

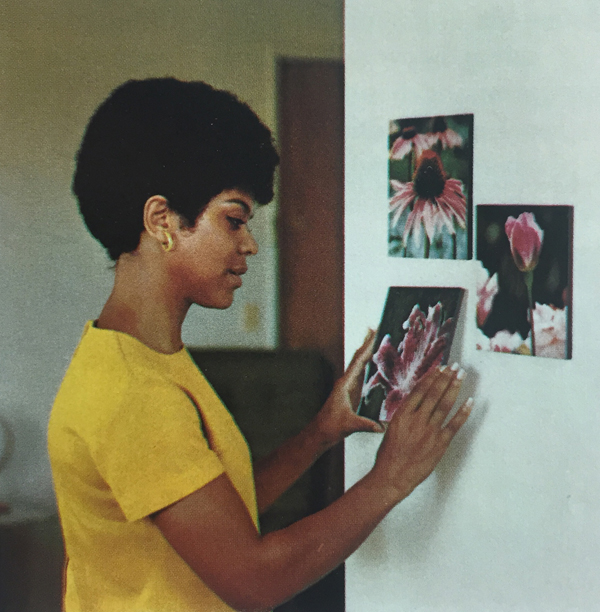

Eastman Kodak Co.

In a discussion under the banner of “Woman with a Camera,” the writer Claire Lehmann plunged into the midcentury archives of Kodak and other film companies, looking to see how women were positioned in educational materials. “It was shocking,” she said, “that women were really only pictured with a camera in hand in very specific poses”—mostly taking pictures of flowers in their backyards. (Men were pictured taking photographs of animals or butterflies.) It was only after feminism’s second wave, beginning in the 1960s, that women began to appear with cameras in titles such as Popular Photography. Lehmann, who discovered the images while researching her groundbreaking essay “Color Goes Electric” (2016), a study of the social reception of color photography in American society, noted in a bit of revisionist feminist art history that it was an exhibition at MoMA in 1966 by Marie Cosindas—not William Eggleston—that was the first moment when color photography was agreed to be “art.” Eggleston as first out of the gate is an oft-repeated myth because his exhibition, in 1976 at MoMA, made a certain kind of “splash.”

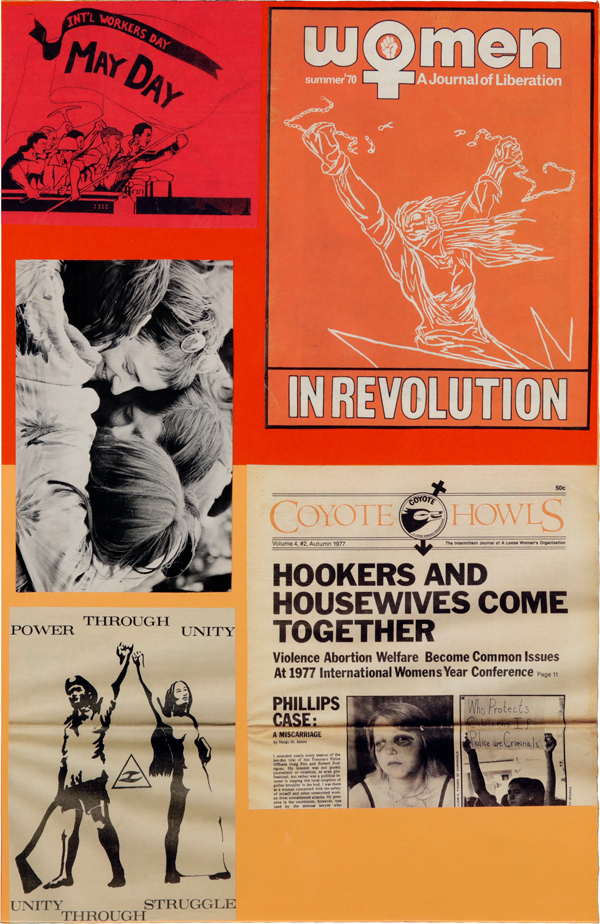

Courtesy the University of Oregon

On the same panel, Carmen Winant, a critic who wrote about a strand of millennial feminism for Aperture’s “On Feminism” issue, and an artist who was recently selected for MoMA’s New Photography showcase in 2018, addressed her work in archives and collage. For the last several years, Winant has been researching ’70s-era feminist separatist communities in the United States. (Winant’s series title, The Answer Is Matriarchy, speaks for itself.) In a radical move, thousands of women left their former lives in the patriarchy behind and tried to build a world without men. But today, separatist strategies are considered dated. Winant’s project looks at a particular moment in American culture—“both utopic and exclusionary”—to ask: “Why does feminism—one of the most meaningful social movements to emerge from the twentieth century—continue to flounder, and in some ways, fail, as a political strategy?” Winant examines how, in their own pictures, separatists framed their experience, their “righteous experiment.”

Courtesy the artist

In her solo talk “Photography in an Intersectional Field,” the writer Aruna D’Souza returned to the third rail of the art world in 2017: the controversy of Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket (2016) at the Whitney Biennial. In her painting, Schutz, a white woman, had rendered a painful depiction of Black history: the image of the teenage Emmett Till in his open casket, photographs of which were published in Jet magazine in 1955 and subsequently galvanized a sense of Black solidarity nationwide. The scorching debate around Schutz’s painting obscured what was the most diverse biennial in the Whitney’s history, but D’Souza’s point was that, if images hurt us, we have to investigate the reason why. Although D’Souza didn’t say so explicitly, it became clear that Mamie Till Mobley, who agreed to publish the images of her son’s open coffin in Jet, was in her own way an agent—a woman controlling the visual narrative in a time of extraordinary pain. Could Mobley’s framing of her son’s image be read as a feminist action? That question would merit a conference unto itself.

© the artist

The final event of “Second Century,” which took place in the august setting of the Anderson Theater at Cincinnati’s Memorial Hall, brought together Tabitha Soren and Justine Kurland in conversation about their lives and work. Each opened the dialogue by reading a prepared statement. Kurland, who is known for her photographs of road trips throughout American landscapes, read from an essay originally published in Cabinet, explaining why she sold her fabled van in which she crossed the country. “I would like to publicly renounce a belief system that once seemed useful and true to me; I’ve outgrown the romantic escapism of this mode of travel.” Meandering, as her photographic essays do, Kurland described the physical and symbolic space of her van (or vans: there was a progression of them, starting with her mother’s). As a child, her mother once yanked a man from the van who was kissing Kurland’s teenage sister. That man seemed to violate not only a person, but also a territory. “I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that the van was a feminist space,” Kurland said.

© the artist

Kurland and Soren discussed how their work explores “masculine” themes—baseball for Soren, cars and guitars for Kurland—but from distinctly female points of view. The two photographers weren’t necessarily addressing feminist artistic action in a time of crisis, but in considering the interface between art and politics, Kurland was circumspect. Thinking about women’s art in terms of solidarity and sentiment, she referred to the scholar Lauren Berlant, and noted, “Women are really good at giving a sense of belonging, but to think about that as a political tool is weak politics.” Women’s art “can only be in proximity to politics; it can’t enact anything politically.” It’s the constant, impossible demand on artists: can art make social change? The answer is no, or at least in the utilitarian notion of change as immediate and impactful. “We’ll march at a protest,” Kurland said. “We might write to our congressmen. But there is still room in art to talk about personal expression.”

© the artist

At the end of her essay for the FemFour’s catalogue on protest art, Maria Seda-Reeder writes, “I need my sisters around me now more than ever.” It’s a slogan, however heartfelt and expressive of solidarity, that has become all too common in the last year. “Now more than ever” implies that we have crossed some kind of threshold. But that’s misleading. “Now” was Election Day 2016; “now” was the day when Donald Trump insulted a Gold Star family (the first time); “now” was the day that voters—men and women—defended Trump’s misogynist language in the Access Hollywood tape; “now” was the moment, in 2015, when Trump himself descended the Trump Tower escalator to declare his presidency. November 8, 2016, didn’t mark a break; it described a continuum.

Eastman Kodak Co.

Still, the arguments between second and third wave feminism, between the radical feminism of 1970s separatists and the neoliberal, one-percent, “lean in” feminism of the Sheryl Sandberg era, appear almost innocently theoretical these days. What about women living in poverty? Without access to health care? Who aren’t earning equal pay? There’s no “more than” when it comes to the truly intersectional social issues of feminism, which can’t fully be redressed by art, and which would still be with us if a woman occupied the White House. Republican women in “Trump Country” need feminism, too.

In 2000, bell hooks, as usual on point and ahead of her time, declared, “feminism is for everybody.” “Imagine living in a world where we can all be who we are,” she wrote, “a world of peace and possibility.” We have a long way to go. Whereas feminism might once have been seen as optional, as a political movement one could opt in or opt out of, or indeed be excluded from, emergency feminism—the political energy unfolding today—demands the widest possible participation. In this “second century,” we’re all feminists now, whether we like it or not.

The FotoFocus symposium “Second Century” took place on October 7, 2017, in Cincinnati, Ohio.